Around fifteen years ago, a mother and her 17-year-old daughter presented to my rooms requesting a referral to a plastic surgeon to ‘fix the daughter’s prolapsed vagina’. Aside from being an unusual request, what took me by surprise was that an appointment had already been made, and they expected me to simply comply with their wishes.

Further questioning revealed that the daughter had had her pubic hair removed for the first time and she was disgusted by the appearance of her newly exposed labia. The mother also considered her daughter’s appearance to be quite different to her own, reinforcing the notion that her daughter’s genital appearance was ‘abnormal’. They went home and googled for information only to find that the ‘outie’, where the labia minora protrudes beyond the margin of the labia majora, could be corrected surgically with a ‘Barbiplasty’ procedure which was described online as merely trimming the labia minora to achieve an aesthetic ideal that matched their expectations. It sounded easy enough, and a bit like getting a haircut.

On the day they presented to my rooms with the request for the referral, the girl permitted me to examine her but refused to look at herself to point out what it was that disgusted her so much. Despite reassuring them that everything appeared normal and there was no vaginal prolapse, they insisted on keeping their appointment with the plastic surgeon. The girl was not yet sexually active and had been seeing a psychiatrist for a generalised anxiety disorder since the age of 12. My referral included the history, details of our conversation, the lack of need for the surgery and that this was a reaction based mainly upon ignorance regarding genital anatomy. Weeks later, I received a postoperative discharge letter outlining that the labiaplasty procedure was a success. The surgeon’s letter infuriated me, as in my opinion, this was an unnecessary cosmetic procedure driven by the girl’s and mother’s lack of knowledge and skewed expectations.

This consultation highlighted several concerns: both mother and daughter had preconceived notions about ‘normal’ external female genitalia, believing the labia minora should not extend beyond the margin of the labia majora. Anything outside of this was considered abnormal and caused emotional distress. They lacked knowledge of the female genital anatomy and viewed irreversible surgery, discovered online, as an appropriate solution to achieve a genital aesthetic ideal without consideration of possible consequences. Furthermore, the surgeon’s normalisation of their request demonstrated a vast difference in management approaches and heralded a new, opportunistic industry where the internet now shaped views around normal and therefore desirable female genitalia. At that time, my knowledge and experience around labiaplasty and the suite of services under the bracket of ‘female genital cosmetic surgery’ (FGCS), was lacking.

My next steps involved my own Google and literature search which initially led to the discovery of airbrushed images of models with prepubescent looking genitals and media commentary using terms such as “camel toe” and “meat flaps,” among other derogatory descriptors. There was a lack of research around this group of procedures referred to as FGCS, and I learned that it aimed to change aesthetic (or functional) aspects of a woman’s genitalia for non-medically indicated conditions. This comprised of a mostly unregulated set of procedures which can be performed by plastic surgeons, aesthetic doctors (GPs with a special interest), dermatologists, urogynaecologists, gynaecologists and urologists, without any standardised training requirements. Labiaplasty comprises around fifty percent of all FGCS procedures being performed, often for medicalised functional discomfort in tight leisure wear or G-strings, which can include excision of the clitoral hood, tightening of the vagina, plumping or liposuction of the mons pubis and G-spot injections1.

The publications at the time were mostly out of the United Kingdom, United States, Western Europe, and other developed nations where the cohorts were larger and where statistics were similar or higher to those reported in Australia. This prompted me to undertake my own research through the Department of General Practice at the University of Melbourne, as an honorary researcher, and I chose to explore what young women thought was ‘normal’ or desirable looking female genitalia2 and what the role of the general practitioner was in managing requests for FGCS3.

Two penultimate medical students were recruited to undertake the research, and the preliminary findings were shared at the 2014 Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP) Women in General Practice conference, where many GPs shared similar experiences to mine. They felt that there was a need for more information to help them guide their patients. This was “a new dilemma for GPs,”4 which prompted the development of a guide called, Female genital cosmetic surgery – A resource for general practitioners and other health professionals,5 published by the RACGP, in 2015. Alongside this, I instigated a cross-sectional survey exploring knowledge, attitude and practice of general practitioners around FGCS6.

Of the 443 Australian GPs who took part in the study, 97% had been asked by women of all ages about genital normality, 54% had encountered patients requesting FGCS, 35% reported they had requests from girls under the age of 18 years, for female genital cosmetic surgery. More than half the GPs suspected psychological disturbances in their patients requesting FGCS, such as depression, anxiety, relationship difficulties and body dysmorphic disorder, yet most of the girls cited concerns about the size of their labia as the reason for wanting cosmetic surgery.

Requests for surgery for 15-24 year olds were the same for 25-45 year olds. The climb in requests highlights the power of socio-cultural factors that medicalise functional discomfort such as chafing, combined with emotive online marketing promising a youthful, desirable ‘vagina’, has fuelled an epidemic of genital anxiety. The three-fold increase in requests for nationally funded labiaplasty procedures, for the period from 2001-2011, reflected this and prompted a review of Medicare claims7 which resulted in new restrictions to medically indicated diseases with specific item numbers for repair of congenital anomalies, female genital mutilation and another for vulval hypertrophy.

The Medicare item number for labiaplasty or vulvoplasty (35534) is now restricted to patients aged 18 years or more who present with structural abnormalities causing significant functional impairment or extends more than eight centimetres below the vaginal introitus when standing. Girls under 18 years of age, must undergo mandatory psychological assessment and observe a 3-month cooling off period which is in contrast with the British Society for Paediatric and Adolescent Gynaecologists, which states that genital cosmetic surgery be delayed until after 18 years of age, which is when full genital maturity is achieved8. Following the Medicare review in 2014, a significant reduction of measurable rates of labiaplasty in Australia ensued, however the number of procedures performed in the private sector remain unmeasured.

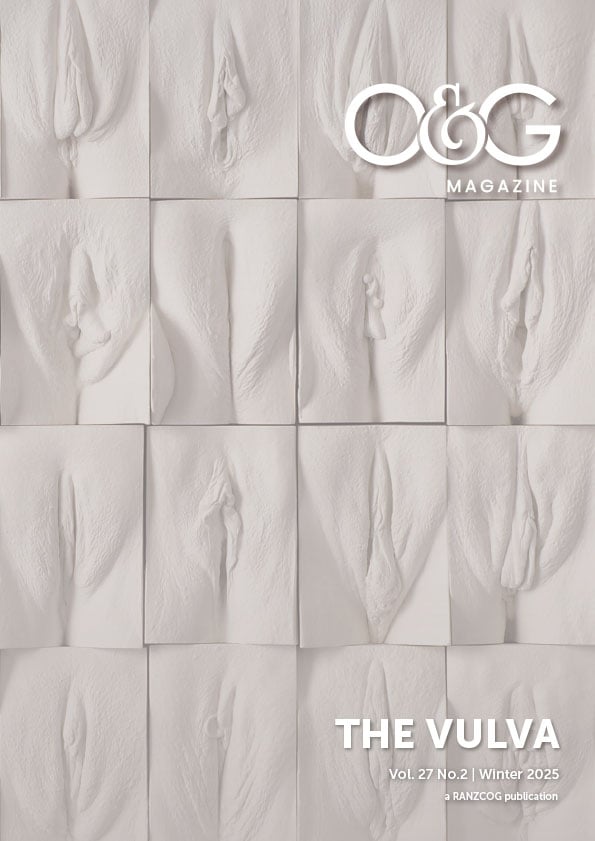

In 2013, Women’s Health Victoria (WHV) addressed misinformation online by developing the interactive Labia Library9. Now in its tenth year, the updated Labia Library depicts genital diversity across various ages, races and from different angles. Despite more than 11 million people accessing the site, rates of FGCS continue to climb10. Celebrities and influencers publicly endorsing procedures to attain a ‘designer vagina’ reinforce prepubertal aesthetic ideals, which inevitably mean we will continue to see women and adolescents who present for all types of FGCS and to which I warn the public around cultural drivers that have potential to cause long term disfigurement or harm, through mainstream media11.

Body enhancement through female genital cosmetic surgery creates ethical and rights dilemmas12 for the clinician and it is our responsibility to educate our patients around genital anatomy and function. The RACGP guide recommends using diagrams to determine what she wishes to have altered, explore her reasons for this request and exclude intimate partner or parental coercion. It is equally important to conduct a psychosexual and gynaecological history and provide her with information around the diversity of genital appearance. Where mental health conditions such as depression, anxiety, or body dysmorphic disorder are suspected, refer for psychological support, regardless of age.

Address all the woman’s concerns around functional discomfort and offer to perform a sensitive examination. Provide reassurance where medical indications for surgery do not exist, discuss physiological changes over the lifespan as there are growth spurts in adolescents which can result in asymmetry which self corrects, changes during and after pregnancy and genital atrophy and shrinkage post menopause. Discuss potential risks of surgery and the lack of evidence regarding outcomes. Explain how marketing terms such as ‘vaginal rejuvenation’, ‘clitoral resurfacing’, ‘G-spot enhancement’ are non-medical terms and lack the rigour of scientific evaluation.

Agency in decision making is a woman’s right however women having little knowledge about their own anatomy and succumbing to social forces that influence the way women feel about their bodies, in the absence of knowing something as fundamental as that the labia minora are second to the clitoris in sensitivity, means that implications of such surgery down that track may well have consequences for those who benefit financially from these procedures.

Conflict of interest

- Women’s Health Victoria (WHV) Board Member 2013-2022

- RACGP Expert Committee for Quality Care 2015-2024

References

- Iglesia CB, Yurteri-Kaplan L, Alinsod R. Female genital cosmetic surgery: a review of techniques and outcomes. Int Urogynecol J. 2013 Dec;24(12):1997-2009. doi: 10.1007/s00192-013-2117-8. Epub 2013 May 22. PMID: 23695382.

- Howarth, C., Hayes, J., Simonis, M., & Temple-Smith, M. (2016). ‘Everything’s neatly tucked away’: young women’s views on desirable vulval anatomy. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 18(12), 1363–1378. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2016.1184315

- Harding, T., Hayes, J.A., Simonis, M., & Temple-Smith, M.J. (2015). Female genital cosmetic surgery: Investigating the role of the general practitioner. Australian family physician, 44 11, 822-5.

- Liao, L.-M. and S. Creighton, Female Genital Cosmetic Surgery: a new dilemma for GPs. British Journal of General Practice, 2011: p. 7-8

- Simonis M. Female genital cosmetic surgery – A resource for general practitioners and other health professionals. The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners, 2015.

- Simonis M, Manocha R, Ong JJ. Female genital cosmetic surgery: a cross-sectional survey exploring knowledge, attitude and practice of general practitioners. BMJ Open. 2016 Sep 26;6(9):e doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013010. PMID: 27678547; PMCID: PMC5051499.

- Australian Government Department of Health, MBS Reviews. Vulvoplasty Report. April 2014)

- Gynaecology, British Society for Paediatric and Adolescent Gynaecology (B.S.f.P.A.), Position Statement: Labial reduction surgery (labiaplasty) on adolescents. 2013.

- Labia Library, Women’s Health Victoria (WHV)

- American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery. ASAPS 2017 Cosmetic Surgery National Data Bank Statistics. 2017

- Simonis M, The Secret Risks of ‘Barbiplasty’ that reality TV doesn’t 19 Sept 2024, The Australian

- Cain, J., et al., Body enhancement through Female Genital Cosmetic Surgery creates ethical and rights dilemmas. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics, 2013. 122: p. 169-172

Leave a Reply