Overview

Vulval conditions make up the bulk of paediatric gynaecology referrals. Whilst children can be affected by many of the same disorders as adults, they can manifest different symptoms and clinical appearances. Always remember that vulval presentations may be the most symptomatic element of a generalised disorder.

The fundamental goal of the vulval examination is to determine whether the skin appears abnormal. Children differ from adults in their engagement during examinations and your capacity to biopsy abnormalities. A full clinical examination should include inspection of extragenital skin, hair, ears and nails.

Baseline photography of the anogenital area to aid treatment review remains underutilised by gynaecologists compared to our dermatology colleagues. Developing a secure system and consent process for taking and storing clinical photographs can make a huge difference to our capacity to monitor treatment response.

A vulval swab has limited utility in premenarchal children, often yielding polymicrobial results. A swab can be considered if inflammation extends to the vagina and discharge is severe, offensive and persistent. Candida species are rarely present prior to oestrogenisation, except in cases of diabetes or significant immune compromise 1. Likewise, vulval biopsy is rarely used. Malignancy is exceedingly rare in children and most benign diagnoses can be made on clinical features and response to treatment2.

Lichen sclerosus

Lichen sclerosus (LS) occurs across all age groups with diagnostic peaks in premenarchal girls and postmenopausal women. There has been considerable debate about clinical monitoring beyond adolescence when LS is diagnosed in childhood. Evidence now supports regular review to prevent architectural and functional consequences4.

Children present with pain and erythema but may also wake from sleep crying or experience pain when voiding or opening bowels5. In severe cases of irritation, there can be bleeding and bruising. Examination findings can be similar to those in adults with pallor and architectural loss. More than 30% can have subepithelial haemorrhage. Purpuric blotches and melanocytic lesions are also associated and can be mistaken for alternative diagnoses5.

Treatment aims to manage symptoms, normalise colour and texture while also limiting architectural disruption. General vulval care advice should always be given. The Royal Children’s Hospital in Melbourne have excellent handouts for parents6.

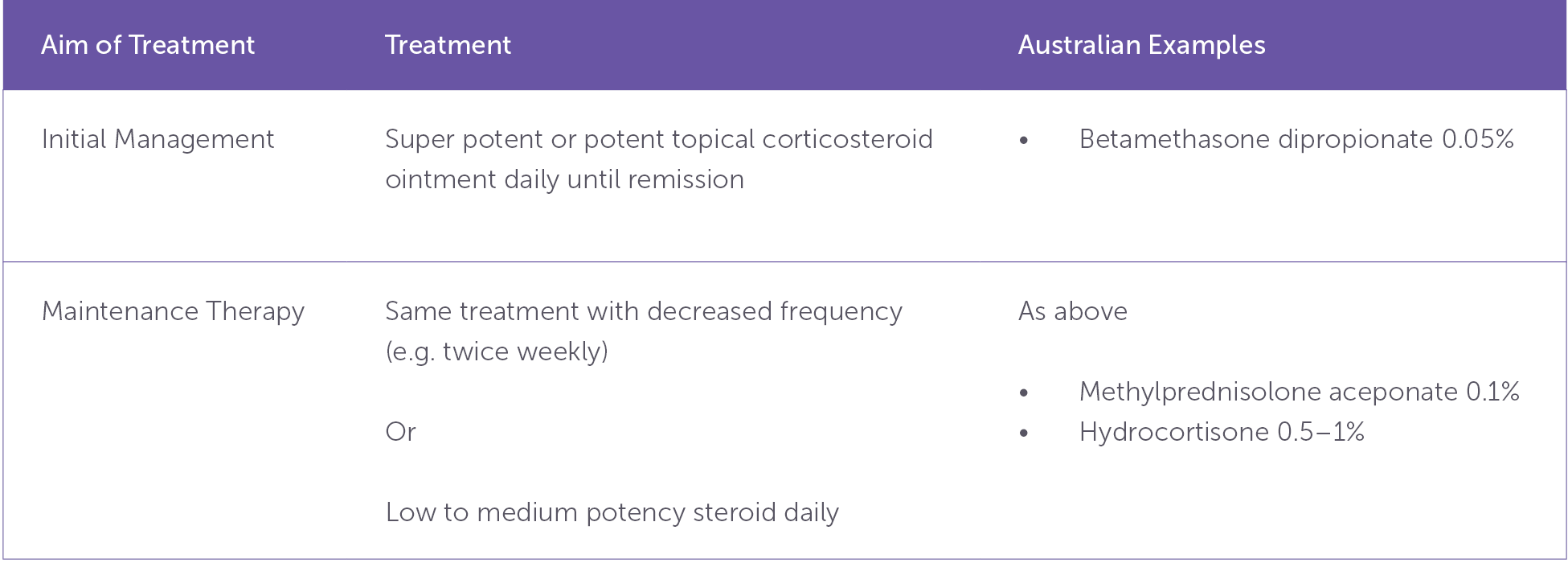

Table 1. Lichen sclerosus management suggestions with Australian examples

Note: Treatment frequency and steroid potency needs to be individualised. Only treating during a flare rarely results in adequate control5.

Psoriasis

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory skin condition. It appears as red plaques, often well demarcated and symmetric, with overlying scale on hair bearing skin (note that scale is not seen in inverse psoriasis). Fissures and maceration can occur within skin folds and the condition favours the perineum and natal cleft, but the vagina is not involved7.

The recognition extragenital involvement (most commonly the scalp) helps to make the diagnosis8. Eye lesions are well demarcated and favour the medial aspect. On the other hand, contact dermatitis extends over the whole of the upper eyelid. Nail changes are common9. Children with psoriasis are at an increased risk of developing diabetes, metabolic syndrome and obesity beginning in adolescence10. Recognising psoriasis provides an opportunity for prevention.

As for LS, psoriasis treatment aims to reduce triggers, calm flares and keep the disease under control. Good vulval care advice should always be given.

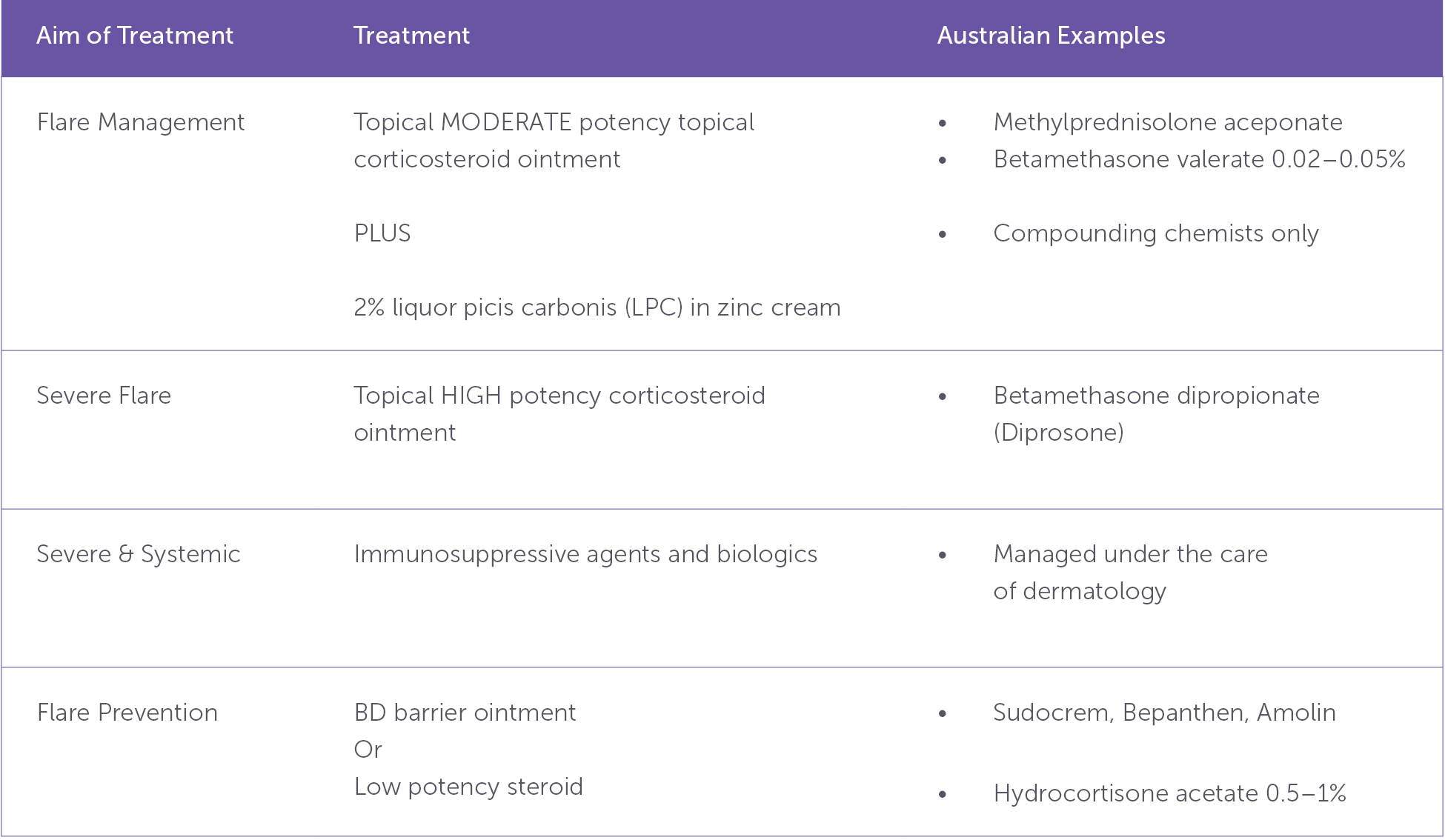

Table 2. Psoriasis management suggestions with Australian examples

Vulvovaginitis

Vulvovaginitis is an umbrella term that when applied to prepubertal girls refers to contact dermatitis. The most common symptoms are pruritus, pain, dysuria and discharge. The vulva and vagina appear erythematous and often have excoriations demonstrated by linear erosions and traumatic vesicles. Severe excoriation can be associated with discharge and bleeding.

The lack of oestrogen in prepubertal girls is the primary contributor to vulvovaginitis. It is also helped along by underdeveloped vulval fat pads, the absence of protective pubic hair, anatomical proximity of vulva and anus and the haphazard techniques employed by children when they first start independent toileting.

Management is often surprisingly straightforward. Parents should be informed that symptoms may flare but are better managed if treatment is commenced early and vulval care continued regardless of symptoms.

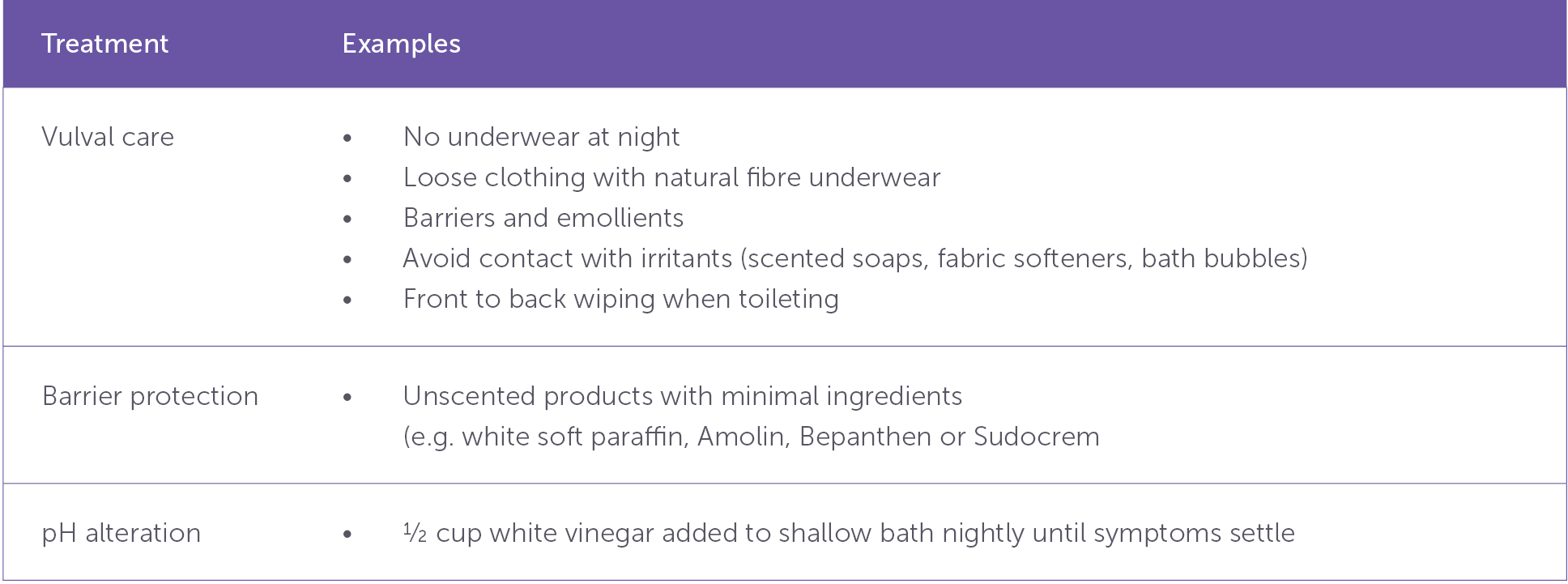

Table 3. Supportive vulval skin care strategies, including barrier protection and pH modification

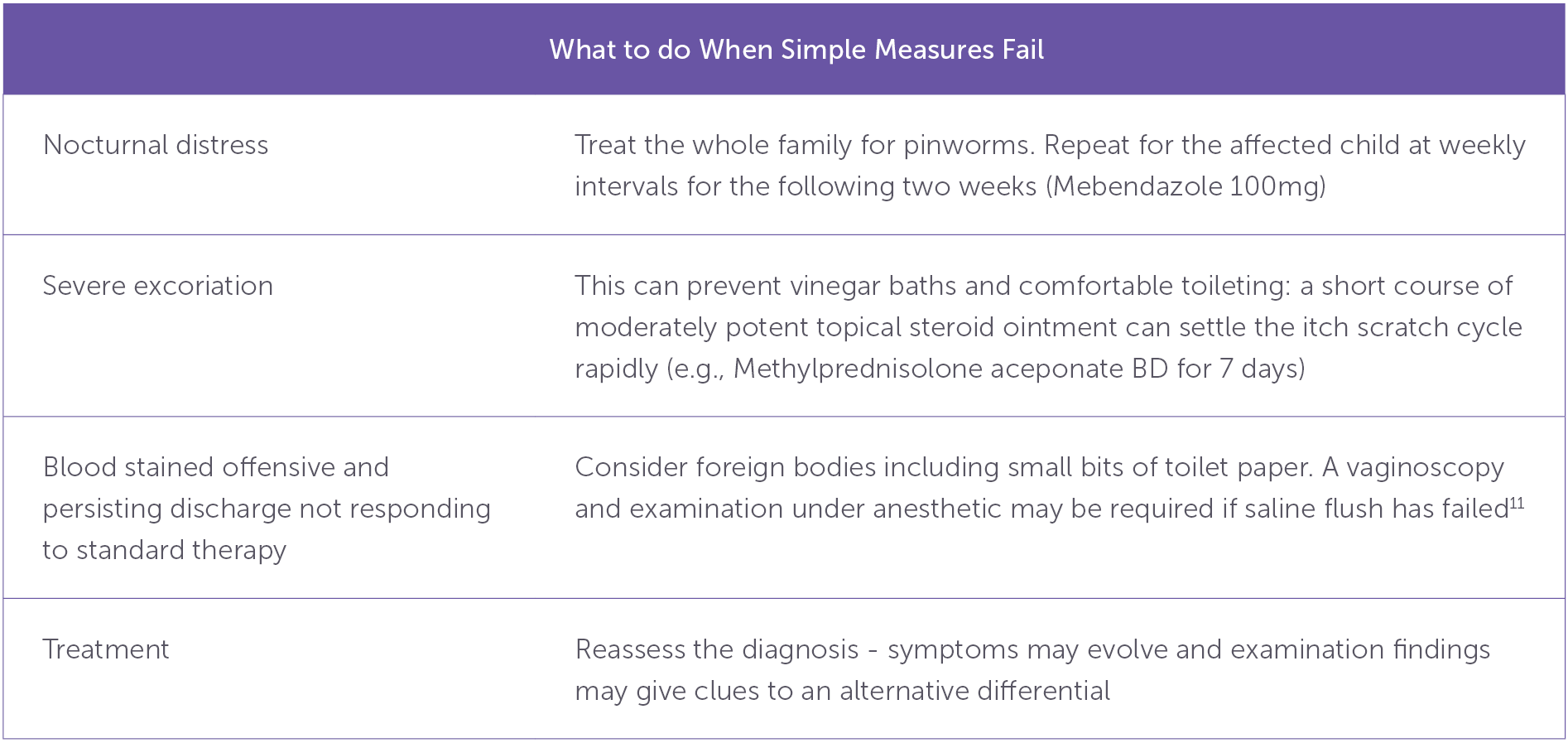

Table 4. Management considerations when first-line vulval care strategies are insufficient

Labial adhesions / fusion

Labial fusion is a variation of normal. Adhesions result from the low oestrogen prepubertal environment and will resolve once pubertal development commences12. There is rarely an indication to treat with oestrogen even when no opening is visible unless the patient is diagnosed with recurrent urinary tract infection or is unable to void. Manual separation in the office is traumatic, poorly tolerated and should never be done. Separation under anesthetic should only be considered in the rare instances adhesions remain after puberty or cause acute urinary retention. Most parents are easily reassured and can be directed to resources such as the Royal Children’s Hospital in Melbourne fact sheets13. Similarly, generalised mild erythema at the vestibule is a normal finding in healthy patients without vulvitis and does not require treatment.

Labial adhesions are often mistaken for the cause of vulval pain and referrals seeking treatment to remedy the pain are common. More often, the discomfort is secondary to concurrent vulvovaginitis resulting from the low oestrogenised environment that is common to both conditions. Reassurance, vulval care and simple vulvovaginitis treatments are often sufficient to alleviate symptoms.

Conclusion

Vulval conditions in children are common. Most are easy to treat with simple measures. Recognising normal variations and confidently reassuring parents is a key component of the paediatric vulval consultation. When an abnormality is identified, it is important to generate a differential diagnosis to direct treatment and measure treatment response. Seek a second opinion from a paediatric or adolescent gynaecologist or dermatologist before proceeding with anaesthetic or biopsy.

References

- Fischer GO. Vulval disease in pre-pubertal girls. Australas J Dermatol. 2001;42:225- doi:10.1046/j.1440-0960.2001.00526

- Morrel B, van der Avoort IAM, Damman J, Mooyaart AL, Pasmans SGMA. A Scoping Review and Population Study Regarding Prevalence and Histopathology of Juvenile Vulvar Melanocytic Lesions. A Recommendation. JID Innov Skin Sci Mol Popul Health. 2022;2(5):100140. doi:10.1016/j.xjidi.2022.100140

- Powell J, Wojnarowska F. Childhood vulvar lichen sclerosus: an increasingly common problem. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44(5):803-806. doi:10.1067/mjd.2001.113474

- Morrel B, Van Der Avoort IAM, Ewing-Graham PC, et al. Long-term consequences of juvenile vulvar lichen sclerosus: A cohort study of adults with a histologically confirmed diagnosis in childhood or adolescence. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2023;102(11):1469-1478. doi:10.1111/aogs.14668

- Day T, Mauskar M, Selk A. Lichen Sclerosus ISSVD Practical Guide to Diagnosis and Management. Ad Médic, Lda; 2024. Accessed 26 Feb, 2025. doi.org/10.59153/adm.ls.001

- Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne Dermatology department. Vulval skin care for children. 2018. Accessed Feb 26, 2025. rch.org.au/kidsinfo/fact_sheets/Vulval_skin_care_for_children/

- Kapila S, Bradford J, Fischer G. Vulvar Psoriasis in Adults and Children: A Clinical Audit of 194 Cases and Review of the Literature. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2012; 16(4):364-371. Doi: 10.1097/LGT.0b013e31824b9e5e

- Wu M, Fischer G. Understanding and Managing Vulvar Psoriasis in Girls: Findings From a Cohort Study. Pediatr Dermatol. 2024 Nov 26. doi: 10.1111/pde.15816. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 39592125.

- Mashal ZR, Elgamal EEA, Zaky MS, Elsaie ML. Dermoscopic Features of Psoriatic Nails and Their Correlation to Disease Severity. Dermatol Res Pract. 2023 May 15;2023:4653177. doi: 10.1155/2023/4653177. PMID: 37223320; PMCID: PMC10202600

- Augustin M, Reich K, Glaeske G, Schaefer I, Radtke M. Co-morbidity and age-related prevalence of psoriasis: Analysis of health insurance data in Germany. Acta Derm Venereol. 2010 Mar;90(2):147-51. doi: 10.2340/00015555-0770. PMID: 20169297.

- Lehembre-Shiah E, Gomez-Lobo V. Vaginal Foreign Bodies in the Pediatric and Adolescent Age Group: A Review of Current Literature and Discussion of Best Practices in Diagnosis and Management. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2024 Apr;37(2):121-125. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2023.11.010. Epub 2023 Nov 25. PMID: 38012979; PMCID: PMC10994743

- Norris E, Elder C, Dunford A, Rampal D. Spontaneous resolution of labial adhesions in pre-pubertal girls. J Paed Child Health 2018; 54(7): 748-753

- Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne. Vulvovaginitis. 2018. Accessed Feb 26, 2025.

Leave a Reply