Treat the WHOLE patient, not just the HOLE in the patient

– an oft-quoted surgical aphorism that still holds true: caesarean wound outcomes hinge on matching technique and dressing strategy to individual risk.

Caesarean section is the most common major surgery worldwide, with a global rate of 21%, projected to rise to 29% by 2030.1 Post caesarean wound morbidity spans surgical site infection (SSI), dehiscence, contact dermatitis, endometritis, seroma and haematoma, with downstream impacts on breastfeeding, readmission and cost. Surgical site infections alone cost, on average, $18,814 per case in 2018-19.2

Risk factors include maternal factors (obesity, diabetes, immunocompromised conditions), intrapartum factors (emergency surgery, prolonged labour or membrane rupture, chorioamnionitis), and technical choices (skin preparation, suture material, and skin-closure technique) which all modulate outcomes. With 10.7% of global maternal deaths attributed to pregnancy-related infection, International Federation of Obstetrics and Gynaecology (FIGO) have recently released best-practice guidance to reduce post caesarean sepsis.3

A practical summary of the literature3

Optimising modifiable risks (correcting anaemia where possible, optimising glycaemic control, smoking cessation, managing infection, and meticulous attention to surgical technique and operative time) is therefore the first “dressing decision” before we even reach for an adhesive.

Antibiotic prophylaxis

A large Cochrane review has long demonstrated that prophylactic antibiotics reduce serious maternal sepsis by 70% and wound infection and endometritis by 60% compared with placebo or no prophylaxis. Building on this, FIGO, World Health Organization (WHO) and National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) now converge on several key principles:

- Timing: a single intravenous dose given 30–60 minutes before skin incision is preferred to maximise maternal protection without compromising neonatal safety. Antimicrobial prophylaxis should be limited to 3 doses within 24 hours.

- Choice of agent: a first-generation cephalosporin (e.g. cefazolin) or ampicillin as first-line, with clindamycin plus an aminoglycoside for women with true beta-lactam allergy.

- Dose adjustment: consider higher doses in women with BMI >30 or prolonged surgery (>2 hours) and additional doses if there is excessive blood loss, but routine multi-dose regimens are discouraged due to antimicrobial resistance and cost.

- Adjunctive Azithromycin: in women having caesarean during labour or after membrane rupture, adding azithromycin to standard prophylaxis further reduces endometritis and SSI.

Skin Preparation

A 2020 Cochrane review4 concluded that skin preparation with chlorhexidine gluconate before caesarean section reduces SSI compared with povidone-iodine. Low-certainty evidence suggested chlorhexidine made little or no difference in endometritis.

Routine pre-operative shaving of pubic hair is not recommended, as it does not reduce infection and may increase microtrauma. Clippers or careful trimming may be used when needed for access.

30-60 seconds of vaginal cleansing with an antiseptic solution (non-alcoholic povidone-iodine or chlorhexidine gluconate) immediately before caesarean reduces endometritis, irrespective of baseline risk.

Surgical Technique

Updated NICE guidance recommends a Joel Cohen-type approach approximately 3cm above the symphysis pubis with blunt dissection of layers to reduce operative and febrile morbidity overall compared to a Pfannenstiel incision (2013 Cochrane review), however effect on reducing SSIs specifically remains uncertain. In women with BMI ≥35, a recent RCT did not demonstrate clear SSI benefit of Joel Cohen versus Pfannenstiel.

Intra-abdominal saline irrigation has not been shown to reduce infection.

Operations exceeding 1 hour with significant blood loss or transfusion carry higher SSI and sepsis risk.

Glove Change

Changing gloves after delivery of the placenta and before closing the abdominal wall is a simple, evidence-based step intervention that reduces SSI. In a meta-analysis of 1,948 women, this practice was associated with a 59% lower risk of wound infection.

Skin Closure

An overview of systematic reviews5 supports closing subcutaneous fat when ≥2 cm to reduce seroma and any wound complications, while differences between scalpel and diathermy or needle type remain uncertain.

Barbed sutures may reduce wound separation versus conventional sutures; evidence is moderate-to-low certainty but reassuring for routine use where surgeon experience supports it.

Absorbable subcuticular skin closure reduces dehiscence compared with staples, with small or uncertain effects on infection, but consistent advantages for lower re-closure and separation rates.

Timing of Dressing Removal

A consistent finding across multiple systematic reviews and randomized controlled trials is that early removal of caesarean wound dressings at 6-24 hours is safe for uncomplicated elective cases and is associated with higher maternal satisfaction with no detriment to wound healing.6 Most sepsis and severe morbidity occurs after discharge highlighting the importance of clear post-discharge education. Notably, increased wound healing complications are seen with high BMI, emergency caesarean, preterm premature rupture of membranes and chorioamnionitis irrespective of when the dressing is removed.7

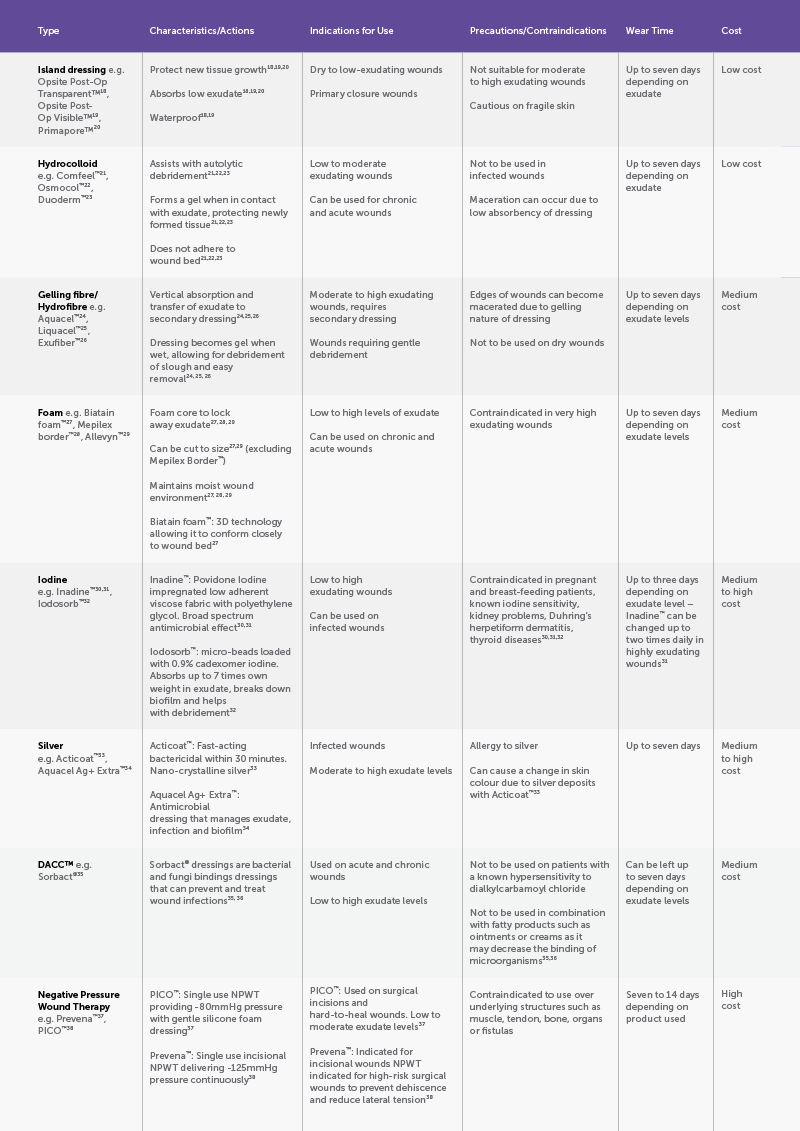

Dressing Type

The 2016 Cochrane overview across primary-intention surgical wounds found no clear SSI reduction with film, hydrocolloid or silver dressings compared with basic contact dressings; certainty was low to very low.8 A CS-specific meta-analysis suggests DACC-coated dressings may reduce SSI, whereas silver dressings do not.9

The European Wound Management Association (EWMA) document “Birth-related wounds: risk, prevention and management of complications after vaginal and caesarean section birth” identifies that whilst some studies report lower SSI rates following caesarean with a DACC impregnated dressing, the selection of a dressing should be based on clinical judgement in conjunction with local policies, current evidence and guidelines.10

At the time of the EWMA document (2020), there was conflicting evidence related to the effectiveness of NPWT (negative pressure wound therapy) for preventing SSIs.10 A subsequent 2023 RCT-only meta-analysis in obese women reported no overall effect on composite wound complications, although NPWT did reduce surgical-site infections without increasing blistering.11 However, trial-sequential analysis did not confirm a full 20% relative reduction, underscoring the need for shared decision-making and local cost-effectiveness considerations.

Overview of Caesarean Wound Dressings

Wound healing progresses through haemostasis (seconds-minutes), inflammation (0-4 days), proliferation (2-24 days), and remodelling (24 days-1 year).12 Surgical incisions are typically repaired for primary intention as precise tissue apposition accelerates epithelialisation and minimises scarring. When this cascade is derailed by infection, dehiscence, hypoxia and/or immune dysfunction, healing shifts to secondary intention, with granulation and delayed epithelial cover, precipitating higher infection risk and poorer cosmesis. Fibroproliferative lesions can extend beyond the original wound margins due to dysregulation and excessive, disorganised collagen, leading to persistent, raised, pruritic keloid plaques with high recurrence. Regardless of pathway, postoperative wound care should be targeted to facilitate timely, uncomplicated healing with the best functional and aesthetic result.

Thankfully, we no longer rely on tea leaves, beer or raw-meat plasters. More than 3000 wound dressings are now available commercially. Wound dressings maintain a moist, thermally stable, low-shear microenvironment that modulates oxygen tension and pH while providing a bacterial barrier and controlled exudate management to support re-epithelialization and orderly tissue repair.13

Conclusion

Optimal caesarean wound outcomes rely on risk-stratified, multidisciplinary care. Adjuncts should be selected case by case, with early involvement of a wound CNC for high-risk women or complex wounds. FIGO’s guidance reminds us that dressing choice is the final step in a prevention chain: from appropriate indications, risk optimisation, timely antibiotics and meticulous technique through to early recognition, education and management of sepsis after birth. Best practice extends beyond the incision.

References

- Angolile CM, Max BL, Mushemba J, Mashauri HL. Global increased cesarean section rates and public health implications: A call to action]. 2023 May 1;6(5). doi: 10.1002/hsr2.1274

- Royle R, Gillespie BM, Chaboyer W, Byrnes J, Nghiem S. The burden of surgical site infections in Australia: A cost-of-illness study. Journal of Infection and Public Health [Internet]. 2023;16(5):792–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2023.03.018

- Ozgok Kangal MK, Regan JP. Wound Healing. Nih.gov. StatPearls Publishing; 2018.

- The Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne. Clinical guidelines (nursing): Wound assessment and management. The Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne. 2023.

- Singer AJ, Dagum AB. Current Management of Acute Cutaneous Wounds. New England Journal of Medicine. 2008 Sep 4;359(10):1037–46.

- Ahmad W, Aquil Z, Alam SS. Historical background of wound care. Hamdan Medical Journal [Internet]. 2020 Oct 1;13(4):189. doi: 10.4103/HMJ.HMJ_37_20

- Holloway S, Harding KG. Wound dressings. Surgery (Oxford). 2022 Jan;40(1):25–32.

- Hadiati DR, Hakimi M, Nurdiati DS, Masuzawa Y, da Silva Lopes K, Ota E. Skin preparation for preventing infection following caesarean section. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2020 Jun 25;(6).

- Gialdini C, Chamillard M, Diaz V, Pasquale J, Shakila Thangaratinam, Abalos E, et al. Evidence-based surgical procedures to optimize caesarean outcomes: an overview of systematic reviews. 2024 May 19;72:102632–2. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2024.102632

- Cenac LA, Guerra S, Huckaby A, Saccone G, Berghella V. Early Wound Dressing (soft gauze/tape dressing) Removal after Cesarean Delivery: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Trials. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology MFM . 2025 Jul 1 [cited 2025 Oct 20];101739–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajogmf.2025.101739

- Kilic GS, Demirdag E, Findik MF, Tapisiz OL, Sak ME, Altinboga O, et al. Impact of timing on wound dressing removal after caesarean delivery: a multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2020 Apr 21;41(3):348–52.

- Peleg D, Eberstark E, Warsof SL, Cohen N, Ben Shachar I. Early wound dressing removal after scheduled cesarean delivery: a randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2016 Sep 1 [cited 2021 Mar 17];215(3):388.e1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.03.035

- Al-Sulaitti Z, Nelakuditi B, Dandamudi BJ, Dimaano KAM, Shah N, AlQassab O, et al. Impact of Early Dressing Removal After Cesarean Section on Wound Healing and Complications: A Systematic Review. Cureus [Internet]. 2024 Sep 30. doi: 10.7759/cureus.70494

- Dumville JC, Gray TA, Walter CJ, Sharp CA, Page T, Macefield R, et al. Dressings for the prevention of surgical site infection. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016 Dec 20;12(12). doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003091

- Wijetunge S, Hill R, Katie Morris R, Hodgetts Morton V. Advanced dressings for the prevention of surgical site infection in women post-caesarean section: a systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 2021 Nov.

- Childs C, Sandy-Hodgetts K, Broad C, Cooper R, Manresa M, Verdú-Soriano J. Birth-Related Wounds: Risk, Prevention and Management of Complications After Vaginal and Caesarean Section Birth. Journal of Wound Care. 2020 Nov 1;29(Sup11a): S1–48.

- Tian Y, Li K, Ling Z. A systematic review with meta‐analysis on prophylactic negative pressure wound therapy versus standard dressing for obese women after caesarean section. Nursing open. 2023 Jun 26;10(9):5999–6013.

- OPSITE◊ POST-OP Transparent Waterproof Dressings | Smith+Nephew Australia. Smith-nephew.com. 2024 [cited 2025 Oct 17].

- OPSITE◊ POST-OP VISIBLE Dressings | Smith+Nephew Australia. Smith-nephew.com. 2019.

- PRIMAPORE◊ Flexible Fabric Dressing | Smith+Nephew Australia. Smith-nephew.com. 2018 [cited 2025 Oct 17].

- Comfeel® Plus Dressing | Coloplast Australia. Coloplast.com.au. 2025 [cited 2025 Oct 17].

- Hydrocolloid Dressings. Sentry Medical. 2024 [cited 2025 Oct 17].

- DuoDERM® Dressings & Patches for Wound Care – Convatec 2022.

- AQUACEL® Hydrofiber® Dressing. ConvaTec.

- L&R Global: Suprasorb Liquacel*. Lohmann-rauscher.com. 2023.

- Exufiber gelling fibre dressing for treating highly exuding and cavity wounds | Mölnlycke

- Biatain® Non-Adhesive | Coloplast Australia. Coloplast.com.au. 2025 [cited 2025 Oct 17].

- Mepilex Border Flex all-in-one foam dressing that stays on and uniquely conforms | Mölnlycke.

- ALLEVYN non-bordered Global. Smith-nephew.com. 2019 [cited 2025 Oct 17].

- InadineTM (PVP-I) Non Adherent Dressing, P01512, 9.5 cm x 9.5 cm, 25/Ct,10 Cts/Cs. Solventum.com. 2025 [cited 2025 Oct 17].

- eIFU – Instructions For Use Information | Solventum. Solventum.com. 2025.

- IODOSORB Global

- ACTICOAT◊ Antimicrobial Barrier Dressings | Smith+Nephew Australia. 2025 [cited 2025 Oct 17].

- AQUACEL® Ag+ ExtraTM. ConvaTec.

- Sorbact® Compress – Sorbact® for healthcare professionals. Sorbact HCP.

- Sorbact® product documentation. Sorbact® product documentation. 2023 [cited 2025 Oct 17].

- Prevena therapy. Solventum.com. 2024.

- PICO◊ Negative Pressure Wound Therapy | Smith+Nephew Australia. 2023 [cited 2025 Oct 17].

Leave a Reply