Viral hepatitis is characterised by liver inflammation, usually caused by the hepatitis viruses A, B, C, D, and E, and less commonly by other viruses such as cytomegalovirus and Epstein-Barr virus. Hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) can cause chronic infection and have implications for perinatal care. This article highlights current recommendations for screening, diagnosis, and management of chronic HBV and HCV in pregnancy.

Chronic Hepatitis B Infection

More than 250 million people have chronic HBV infection worldwide.1 Many will be asymptomatic but may have fluctuating viral activity with subclinical hepatic inflammation that can cause cumulative damage. Untreated, this can lead to liver cirrhosis in up to 40%, as well as hepatocellular carcinoma and liver failure.2

HBV is transmitted through bodily fluids, and acquisition during infancy or childhood leads to chronic infection in approximately 95% of cases,1 with the remaining 5% spontaneously clearing the virus. Maternal HBV infection is therefore important to diagnose during pregnancy as this provides an opportunity to prevent transmission to the infant, and institute care for the mother to lower the chance of long-term liver complications.

Screening and Diagnosis

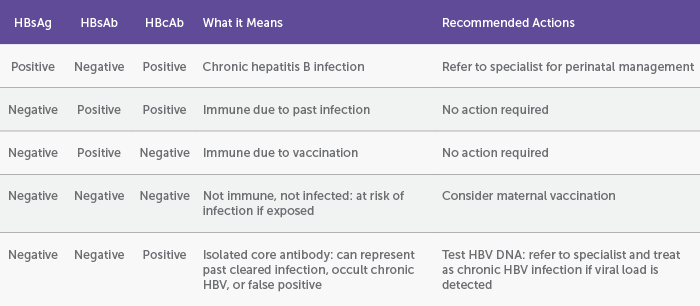

In Australia, antenatal testing includes universal testing for HBV using hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg). If HBsAg is detected, further investigations are warranted with hepatitis B surface antibody (HBsAb) and hepatitis B core antibody (HBcAb).3 These results are used to distinguish between those who have chronic infection, those with past cleared infection, and those who are immune from vaccination or have neither been infected nor vaccinated (Table 1).

Table 1: Screening for hepatitis B infection and interpretation of results

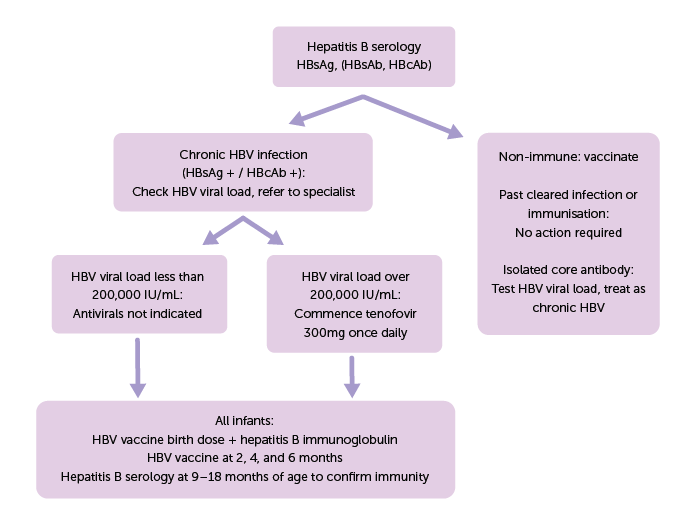

Figure 1: Flowchart for management of chronic hepatitis B infection in pregnancy

Management

All antenatal women diagnosed with hepatitis B should be referred for specialist review to guide perinatal management. HBV viral load testing should be performed in every pregnancy, and if over 200,000 IU/mL it is recommended to commence antiviral therapy, usually with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) 300mg once daily.4 This should be started between 24 to 28 weeks gestation and continued postpartum until specialist review.4 This approach effectively reduces viral load and lowers the risk of perinatal transmission.2 TDF is safe to use in both pregnancy and breastfeeding mothers.1,5

All infants born to mothers with HBV infection, regardless of viral load, should receive a birth dose of HBV vaccination and hepatitis B immunoglobulin, both to be given as soon as possible, and preferably within 12 hours of birth.4,6 A further three HBV vaccinations should be administered at two, four, and six months of age, and are included in the routine childhood immunisation schedule. Pre-term babies may require booster doses.6 All infants should have serology performed between 9 to 18 months of age to ensure they are immune, to identify those who may need additional doses of hepatitis B vaccine, or to identify the few who may have contracted HBV perinatally.4 Partners and other household contacts should also be tested and vaccinated if needed.

Other Considerations

Having HBV infection should not affect the mode of delivery. Caesarean section does not provide protection against perinatal transmission over vaginal delivery, and decisions should be based on other obstetric factors.4

Postpartum, it is safe to breastfeed regardless of viral load, and when taking TDF. Antivirals should be continued for around 12 weeks postpartum with specialist review to guide cessation, as women may have a postpartum hepatitis flare on ceasing antiviral therapy.

All patients should be linked in with a specialist for longer-term monitoring and surveillance for complications.

Hepatitis C Infection

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is an RNA virus which affects around 71 million people worldwide.7 It is acquired through exposure to bodily fluids and can be bloodborne or sexually transmitted. It causes both acute and chronic infection, with around 70% of cases leading to chronic infection. Long-term complications include liver fibrosis, cirrhosis and liver cancer, all of which carry higher risk of morbidity and death.7

Chronic HCV infection with detectable viraemia is associated with approximately 5% risk of perinatal transmission.4 Antenatal screening may identify previously undiagnosed cases of chronic HCV infection. Many organisations, including the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RANZCOG), now recommend universal testing for all pregnant women rather than a risk-based screening approach.3

Screening and Diagnosis

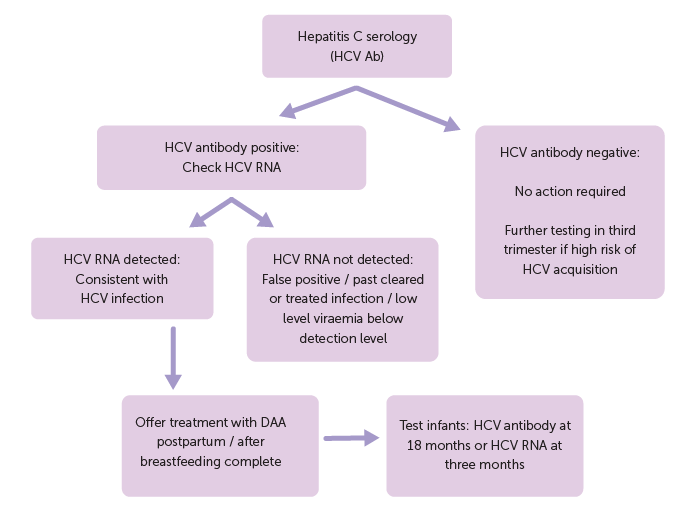

Hepatitis C antibody testing is used for screening. For those with a positive HCV antibody, it is important to do a test for viraemia. This can be done using either a quantitative test (viral load) or a qualitative HCV PCR test (reported as detected or not detected).

An undetectable viral load most commonly indicates past cleared HCV infection, previous successful treatment (cure), or low-level viraemia below the level of detection.4 In these cases, the risk of perinatal transmission is considered negligible.

When HCV is detected, this confirms the diagnosis of current HCV infection and specialist review is recommended to discuss the implications for both mother and infant.

Figure 2: Flowchart of testing and management for Hepatitis C infection

Management

Direct-acting antivirals (DAA) such as sofosbuvir and velpatasvir are effective medications that can cure chronic HCV infection in over 98% of cases, defined as sustained virological remission with continued undetectable viral load at 12 to 24 weeks post-completion of treatment.6 Safety data on the use of DAA in pregnancy and breastfeeding is still being collected. While current Australian guidelines do not recommend the use of DAA in women who are pregnant or lactating, this may change as emerging data suggests a reasonable safety profile. Until then, women should be offered treatment with DAA once they have completed the pregnancy and breastfeeding; and ideally before any future pregnancies.4

Women who become pregnant whilst already taking DAA should be offered early specialist review to discuss the risks of continuing treatment versus stopping.4

In the setting of HCV infection, there is no evidence to recommend caesarean section over vaginal delivery. Amniocentesis is recommended over chorionic villus sampling, and it is recommended to minimise invasive procedures such as fetal scalp electrodes.4,7

Other Considerations

HCV antibodies are not protective against re-infection, and women and their partners should be counselled about ongoing risk of re-infection and offered re-testing if indicated.

Breastfeeding is considered safe. However, if the mother experiences nipple trauma with bleeding, they should be offered early lactation support and advised to express and discard milk from the affected side until it heals.

Infants born to mothers with a detectable HCV RNA test should be followed up with either an HCV RNA test done at three months of age, or a hepatitis C antibody test performed at or after 18 months of age. The HCV RNA test may incur a cost but may reduce the risk of loss to follow up.4

Infants with confirmed HCV infection should be referred to a specialist paediatrician, either gastroenterologist or infectious diseases physician, for management.4,8

Similarly to hepatitis B, it is important that women with chronic HCV are linked into specialist care postpartum to ensure they receive treatment, and that they are assessed for complications of chronic HCV infection.4

References

- Prevention of mother-to-child transmission of hepatitis B virus: guidelines on antiviral prophylaxis in pregnancy. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020.

- Tang LSWYM, Covert E, Wilson E et al. Chronic Hepatitis B Infection: A Review. JAMA. 2018; 319(7): 1802-1813.

- Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RANZCOG). Best Practice Statement: Routine antenatal assessment in the absence of pregnancy complications. March 2022.

- Australian Society of Infectious Diseases (ASID). Management of Perinatal Infections. Third Edition. Sydney, 2022.

- Hu YH, Liu M, Yi W et al. Tenofovir rescue therapy in pregnant females with chronic hepatitis B. World J Gastroenterol. 2015; 21: 2504-2509.

- Australian Immunisation Handbook 7th Edition.

- Seto MT, Cheung KW, Hung IFN. Management of viral hepatitis A, C, D and E in pregnancy. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2020; 68: 44-53.

- Australasian Society for HIV Medicine (ASHM). HCV in Children: Australian Commentary on AASLD-IDSA Guidance. March 2024.

Leave a Reply