Cervical cancer remains a major — though declining — public-health concern in Australia. Sustained vaccination and screening efforts have positioned Australia to reach the cervical-cancer elimination threshold (<4 cases per 100,000 woman-years) by 2035, leading the world in cervical cancer prevention.1 In 2023 7% of patients screened were found to have oncogenic Human Papillomavirus (HPV), with exposure to high-risk HPV types 16 and 18 cause over 75 per cent of invasive cancers in Australia, with other oncogenic strains contributing to the remainder.2,3

Antenatal consultations provide a good opportunity to engage patients who may otherwise be under- or never-screened.4 For many, pregnancy represents their first consistent interaction with the health system. Offering cervical screening within antenatal care not only supports individual patients but also contributes to national elimination targets.

The 2024 Australian Institute of Health report recorded 835 new histologically confirmed cases of cervical cancer and a 73.1 per cent screening participation rate among women aged 25–74 between 2019 and 2023.3 While encouraging, these figures underline the need to reach the remaining unscreened population.

Integrating screening into routine pregnancy care can help sustain Australia’s progress toward elimination.

Key messages:

- Cervical screening during pregnancy is safe.

- Self-collection is a validated, effective option.

- Embedding screening into antenatal pathways can improv e accessibility and, if required, support follow-up.

Safety of Cervical Screening in Pregnancy

The Australian Centre for Prevention of Cervical Cancer, Cancer Council Australia, and Cancer Institute NSW confirm that cervical screening is safe at all stages of pregnancy.4,5,6 The NCSP Quick Reference Guide (2025 update) describes pregnancy as “an ideal opportunity to offer screening if due or overdue”.7

Self-collected vaginal samples have equivalent sensitivity as clinician-collected cervical samples for the detection of HPV and cervical intra-epithelial neoplasia 2+ (CIN 2+)4,5,7,8 Both options are suitable in pregnancy and should be offered according to patient preference.

Self-collection offers particular advantages:

- Comfort and acceptability: avoids speculum use and minor bleeding sometimes associated with taking a sample from a vascular cervix in pregnancy. If a clinician-collected sample is preferred or required, a cervix broom (not an endocervical brush) should be used.4

- Accessibility: can be performed quickly during a routine antenatal visit, including with clinician assistance if requested (e.g. for someone with disability).

Prior to offering screening, a history should be taken from patients to determine if they have symptoms suggestive of cervical cancer. These include abnormal bleeding such as postcoital bleeding, persistent intermenstrual bleeding, or postmenopausal bleeding, along with unexplained persistent unusual vaginal discharge. These symptoms make the patient ineligible for self-collect and require a clinician examination and a co-test. Patients should be advised to follow up with their GP if these symptoms arise prior to their next due screening.4

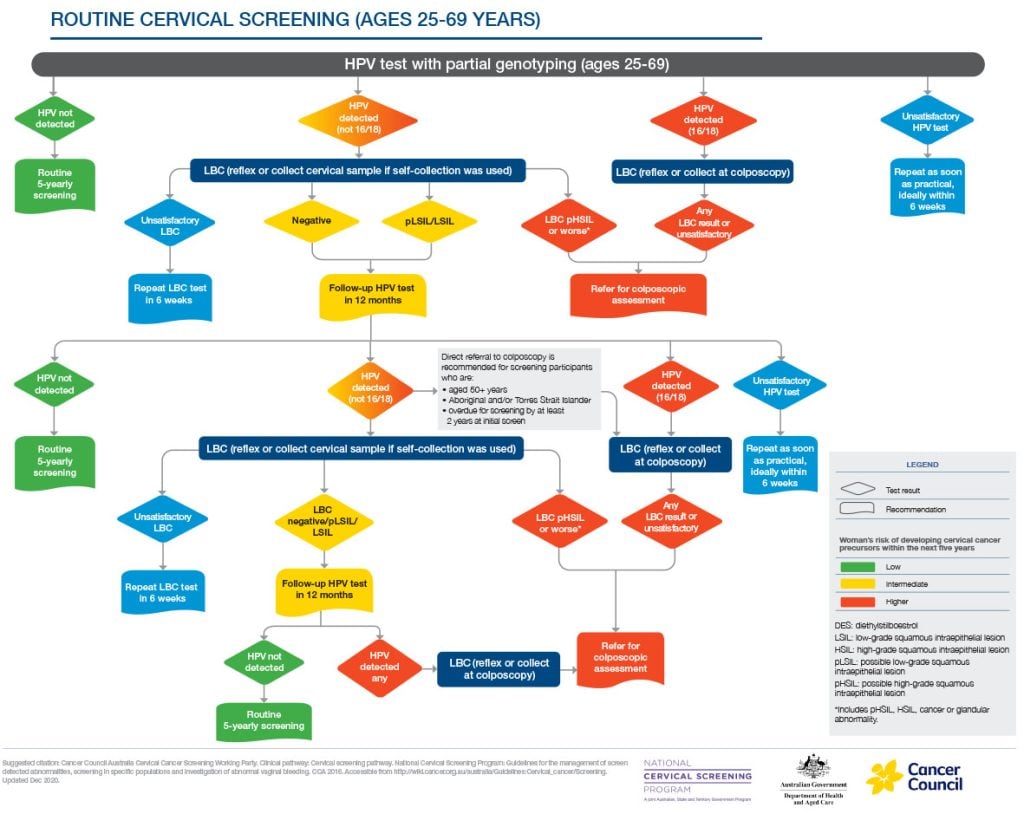

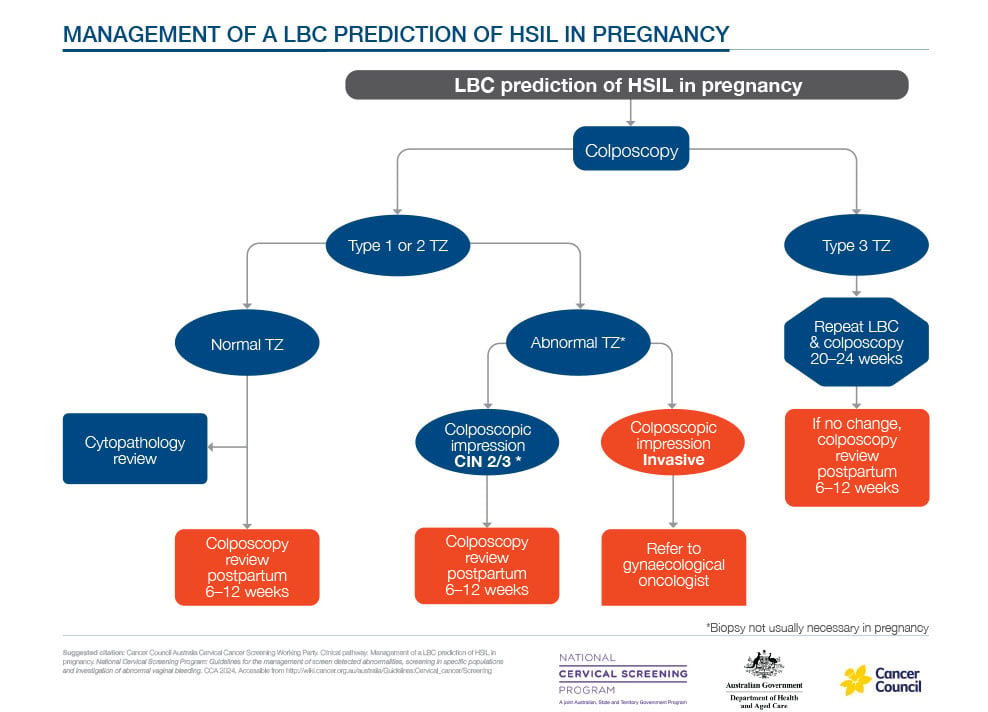

Timely colposcopy is recommended if HPV 16/18 is detected, or HSIL on cytology is detected if an HPV (not-16/18) result. HSIL can be detected on either reflex liquid-based cytology (LBC) on a clinician collected sample or at a return visit for an LBC test after self-collection.4

Colposcopy is also safe in pregnancy. Its aim is to exclude invasive disease and provide reassurance. Ideally, it is performed by an experienced colposcopist; biopsy or treatment should be reserved for suspected invasion. Most high grade squamous intrapithelial lesion (HSIL) lesions regress or remain stable during pregnancy.9,10

These safeguards confirm that pregnancy is not a reason to defer cervical screening.

Accessing the NCSR Healthcare Provider Portal

General practitioners, specialists, nurses, lab staff, and other authorised delegates (with approval) can access the National Cancer Screening Register (NCSR) through the Healthcare Provider Portal. Access to the NCSR may also be available through practice management software in your practice

How to apply:

- Create or log into PRODA — a verified Provider Digital Access account through Services Australia

- Once logged in, select the Healthcare Provider Portal tile

- Link your provider number(e.g. Medicare provider number, RIN or STAN) to activate access.

- Review and accept the Terms and Conditions

- For staff without provider numbers (e.g. nurses or administrative staff), the nominated provider can grant delegate access

Tip: The NCSR website includes a short instructional video and detailed step-by-step guide for first-time users.

Reference: National Cancer Screening Register. Healthcare Provider Portal User Guide.

Integrating Screening into Antenatal Pathways

Cervical screening is not yet a formal component of the “early pregnancy bundle” (such as dating ultrasound or first-trimester bloods). Nevertheless, any patient found to be due, overdue, or symptomatic should be offered screening (or appropriate investigation) at that appointment, with results checked via the NCSR to avoid inadvertent patient billing.11

Early integration – ideally at the first GP antenatal consultation – would allow results to accompany referrals to obstetric services and streamline follow-up. Embedding screening early supports continuity of care, aligns with national elimination goals, and prevents missed opportunities.

Practical Tips

- Check screening history at booking using the NCSR portal.

- Offer choice between self- and clinician-collection, explaining pros and cons and screening for symptoms.

- Prepare logistics: ensure appropriate swabs/cervix brooms are available; label samples clearly (include pregnancy status and collection type).

- Counsel patients: normalise HPV infection and clarify that a positive result signals infection, not cancer.

- Follow NCSP protocols: manage results per 2025 guideline flowcharts, with colposcopy referral when indicated.

Future Directions and Challenges

- Equity: Antenatal self-collection may especially benefit under-screened groups, including Culturally and Linguistically Diverse patients, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients, and those in rural or remote areas.12,14 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women remain nearly twice as likely to develop, and three times as likely to die from, cervical cancer as non-Indigenous women.15

- Provider familiarity: Some clinicians remain hesitant about antenatal screening; continued education and clear guidance are essential.

- System integration: Linking the NCSR with practice-management software would make screening history more visible and opportunistic screening more routine.

- Embedding cervical screening into antenatal care — particularly through self-collection — offers a practical, equity-focused path to elimination.

Conclusion

Cervical screening in pregnancy is safe, effective, and essential for those who are due or overdue. The availability of self-collection provides a comfortable, patient-centered pathway to reach those who might otherwise be missed. Integrating this into antenatal care supports both individual health and Australia’s world-leading progress toward cervical-cancer elimination.

In short: antenatal HPV screening is good medicine, good public health, and a chance not to be missed.

References

- Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care. National Strategy for the Elimination of Cervical Cancer in Australia: A pathway to achieve equitable elimination of cervical cancer as a public health problem by 2035. November 2023.

- Brotherton JML. How much cervical cancer in Australia is vaccine preventable? A meta-analysis.Vaccine. 2008 Jan 10; 26(2):250–256. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.10.055

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2024) National Cervical Screening Program monitoring report 2024, catalogue number CAN 163, AIHW, Australian Government.

- Cancer Council Australia. National Cervical Screening Program: Guidelines for the management of screen-detected abnormalities, screening in specific populations and investigation of abnormal vaginal bleeding. Section 7.1 Pregnancy. Version 2.22. (2025)

- Australian Centre for Prevention of Cervical Cancer. Cervical screening during pregnancy (2024).

- Cancer Institute NSW. Cervical screening in pregnancy: information for clinicians (2024).

- National Cervical Screening Program. Quick Reference Guide (2025 update).

- RACGP. Self-collection of HPV samples: a guide for GPs (2023).

- ScienceDirect. Natural history of high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia in pregnancy: a multi-centre cohort study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2019.

- International Journal of Gynecological Cancer. High-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion in pregnancy: outcomes and effect of delivery mode. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2024.

- National Cancer Screening Register. Healthcare Provider Portal User Guide. How to interact with the NCSR for Healthcare Providers.

- National Cancer Screening Register. Self-collection for cervical screening at an all-time high [Internet]. Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care; 2024 [cited 2025 Oct 8].

- Powell E, Roe L, Gupta L, et al.Cervical screening approach of self-collection, point-of-care HPV testing, and same-day colposcopy among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women in remote Western Australia (the PREVENT trial).Lancet Public Health. 2025;10(1):e12-e21.

- Saville M, Sultana F, Malloy MJ, Velentzis LS, Caruana M, Keung MH, et al.Self-collection for cervical screening in the renewed National Cervical Screening Program: a cross-sectional study.Med J Aust. 2021;215(8):357-363.e1. doi:10.5694/mja2.51137.

- Brotherton J, Machalek D, Smith M et al., 2024 Cervical Cancer Elimination Progress Report: Australia’s progress towards the elimination of cervical cancer as a public health problem. Published online 14/03/2025, Melbourne, Australia.

Leave a Reply