Background: Why Varicella Still Matters

Varicella-zoster virus (VZV), the cause of chickenpox and shingles, remains a relevant concern in pregnancy despite the success of Australia’s national immunisation program. For most clinicians, the disease is now an uncommon presentation. However, for susceptible pregnant women, exposure to VZV can herald significant consequences to both the mother and fetus. Obstetric doctors, midwives, and general practitioners remain at the front line of assessing risk, counselling patients, and providing time-critical prophylaxis. This article reviews Australian epidemiological trends, outlines practical management of exposure, and explains the spectrum of maternal, fetal, and neonatal risks.

Epidemiology and Immunisation in Australia

Australia introduced a universal varicella vaccination program in 2005, initially as a single dose at 18 months of age. This has had a profound effect on disease burden. National surveillance data has shown that in 2023, more than 90% of Australian two-year-olds were fully vaccinated, and hospitalisations due to primary VZV infection have declined dramatically.1 Breakthrough cases continue to occur, particularly in migrants from regions without routine childhood vaccination.2 Clinicians also encounter women with uncertain or absent immunity.

The vaccine used in Australia is a live attenuated virus. This makes it highly effective, but means it is contraindicated in pregnancy. As a result, ensuring women are immune before conception remains the most reliable means of protecting against VZV in pregnancy. 1

Preconception and Antenatal Screening

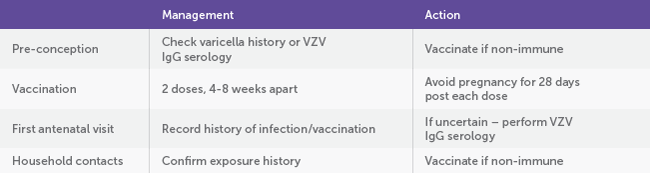

Preconception screening for varicella immunity is essential. Women uncertain of prior infection should have VZV IgG testing, with non-immune women offered two vaccine doses four to eight weeks apart and advised to avoid pregnancy for 28 days post-vaccination.1 During pregnancy, early documentation of immunity and vaccination of non-immune household contacts reduce maternal exposure risk.3

Table 1. Pre-conception and Antenatal Screening

Defining and Managing Exposure During Pregnancy

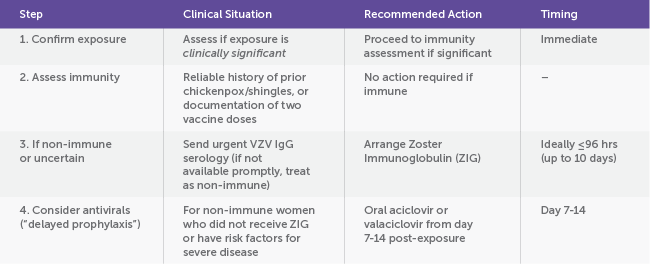

When a pregnant woman reports contact with a suspected or confirmed case of chickenpox or shingles, the first step is to define whether the exposure is clinically significant. Significant exposures include household contact, face-to-face contact indoors for 15 minutes or more, or direct exposure to vesicular fluid.4

Once exposure is established, prompt clarification of the woman’s immune status should be obtained. A reliable history of prior varicella or shingles, or documentation of two doses of vaccine is considered evidence of immunity. If the woman is clearly immune, no intervention is required. However, if she is non-immune or her status is unknown, and results cannot be obtained promptly, then post-exposure prophylaxis should be arranged without delay.3,4

Table 2. Post-Exposure Management in Pregnancy

Maternal Disease: When Chickenpox Turns Dangerous

Chickenpox in adults is far from benign, and pregnancy amplifies the risks. The physiological changes of pregnancy, particularly the relative immunosuppression and reduced pulmonary reserve, predispose women to severe varicella pneumonitis, the most feared maternal complication.4 Pneumonitis develops in up to 10–20% of infected pregnant women, often presenting with dry cough, dyspnoea, and hypoxaemia within days of rash onset. Mortality rates can approach 10% in untreated cases, rising with advancing gestation. 5,6

From an MFM perspective, early recognition and antiviral therapy are life-saving. Intravenous or high-dose oral aciclovir should be initiated ideally within 24 hours of rash appearance, reducing both disease severity and maternal morbidity. Hospital admission is indicated for women with respiratory compromise, comorbidities (e.g. asthma, smoking, obesity), or those in the second or third trimester, when pulmonary complications are more likely.4,5

Beyond maternal risk, active varicella poses a significant infection control challenge. Women are contagious from 48 hours before rash onset until all lesions have crusted, necessitating strict airborne and contact precautions. For tertiary units, ensuring negative-pressure isolation and staff immunity verification is critical to preventing nosocomial spread.3,4

Fetal and Neonatal Risks

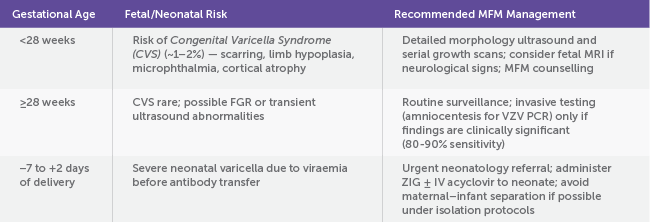

The fetal and neonatal consequences of VZV infection depend on the gestational age of infection, influencing both prognosis and management.4,5,7

Table 3. Fetal Risks and MFM Management

While the universal varicella vaccination program has reduced community circulation, varicella remains a potential threat in pregnancy. Clinicians must be adept at recognising significant exposures, rapidly assessing immunity and arranging timely prophylaxis.3,4 Understanding the fetal and neonatal risks by gestation allows for appropriate counselling and surveillance. Above all, pre-conception vaccination remains the most effective prevention strategy.1 As with many infections in pregnancy, a proactive approach grounded in clear communication with infectious diseases and neonatology teams ensures optimal outcomes for both a mother and her baby.

References

- Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care. Australian Immunisation Handbook: Vaccination for Women Who Are Planning Pregnancy, Pregnant or Breastfeeding. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia; 2024.

- Sauerbrei A, Wutzler P. Varicella-zoster virus infections during pregnancy: epidemiology, clinical symptoms, diagnosis, prevention and therapy. Curr Pediatr Rev. 2004;30(4):353-60. doi:10.2165/00003495-200464040-00004

- SA Health. Varicella (Chickenpox) in Pregnancy – SA Perinatal Practice Guidelines. Government of South Australia; 2015.

- Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Chickenpox in Pregnancy (Green-top Guideline No. 13). London: RCOG; 2022.

- Heuchan AM, Isaacs D; Australasian Society for Infectious Diseases. Management of varicella-zoster virus exposure and infection in pregnancy and the newborn. Med J Aust. 2001;174(6):288-92. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2001.tb143436.x

- Enders G, Miller E, Cradock-Watson JE, Bolley I, Ridehalgh M. Consequences of varicella and herpes zoster in pregnancy: prospective study of 1739 cases. Lancet. 1994;343(8912):1548-51. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(94)93043-3

- Australasian Society for Infectious Diseases. Management of Perinatal Infections. 3rd ed. Sydney: ASID; 2022.

Leave a Reply