Typically, lactation follows pregnancy and childbirth. Less well known is that the timing can be more fluid (excuse the pun) and that lactation can be induced without a pregnancy.

Induced lactation allows a woman who has not given birth to breastfeed or provide breastmilk to a child, and may be desired in situations such as adoption, surrogacy or production of milk for an infant born to a women’s partner/sister. Women seeking induced lactation may never have been pregnant nor lactated previously (nulliparous women) or may have lactated before but not the birth mother for this baby. Previous birth or lactation experience is not necessarily required. The process of induced lactation is assisted by mimicking the physiology of breast changes that occurs during pregnancy and early postpartum, using a combination of pharmacological and non-pharmacological techniques.1

Physiology

During pregnancy, increased levels of oestrogen, progesterone and prolactin support the pregnancy but also prepare the breast for lactation.2 Oestrogen stimulates proliferation of the glandular tissue, while progesterone is mainly responsible for the proliferation of the ducts and lobules. After childbirth and removal of the placenta, oestrogen and progesterone levels drastically drop, allowing prolactin to initiate milk production. The ongoing production of milk is known as galactopoesis and relies on the regular removal of milk. We refer to this phase as under autocrine (or local) control.

Benefits

Induced lactation may be an option for women starting a family using surrogacy, as it allows them to experience the process of breastfeeding, which facilitates bonding as well as providing nutrition and immunity for the newborn. When families are planning to adopt an infant or young child, timing is usually uncertain, which makes planning the steps for induced lactation more difficult and success may be measured in the emotional attachment rather than milk supply.3 4 Some families have found that older adopted children benefit from the bonding effects of breastfeeding.5 Same-sex female couples may also consider the option of the partner inducing lactation or relactating (if they have breastfed in the past) in order to provide more options for feeding and caring for their newborn/s.

Regimen

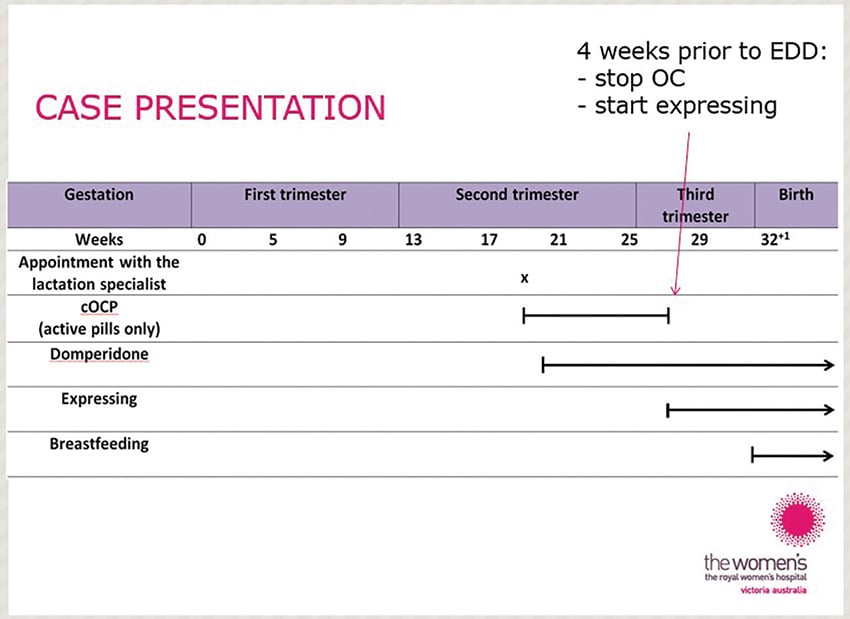

A typical regime is to commence a combined oral contraceptive (COC) like Microgynon 30 EDTM on a daily basis, three to five months prior to the expected due date (EDD). The aim is to mimic pregnancy, so the usual monthly break is not needed. After a week or so, the galactogogue domperidone can be added (usually 10mg ii tds) and this continues as long as needed. Usually the COC is stopped about six weeks prior to the EDD, mimicking the end of pregnancy, and breast expression is started immediately.6 The combination of these medications usually causes breast fullness, and demonstration of the technique of hand expression will usually elicit drops of clear or cloudy milk. Once the COC is ceased, breast massage and hand expression are recommended three hourly or so, to simulate the infant feeding and stimulate the onset of milk production. When the milk volume starts to increase, an electric pump can be carefully used.

Considerations

A detailed medical history is needed prior to this regime, and in practice some women will have contraindications to oestrogen or domperidone. If oestrogen is contraindicated, the minipill (progesterone only) could be used as an option. Domperidone is commonly used off-label for lactation stimulation, but is contraindicated in people with a history of cardiac irregularities or if taking another medication that potentially increases the QT interval.7 8 An ECG could be ordered to check the corrected QT interval prior to commencement, but is not mandatory.9 10

Success of induced lactation should be discussed in relation to the mother’s feelings about her breastfeeding experience rather than the quantity of milk produced or how long she breastfeeds. There are no guarantees of obtaining a full milk supply with induced or relactation, but any milk production will be considered a huge success for some women. The goal is not exclusive breastfeeding. Additional milk (infant formula or donor milk) can be given using a supplemental feeding tube at the breast. Using a feeding line ensures the infant is receiving adequate nutrition and is stimulating milk supply at the same time.11

Here are a couple of examples of induced lactation in practice:

The female partner of a woman expecting monochorionic monozygotic twins was referred to the breastfeeding service at the Royal Women’s Hospital, Melbourne, as birth was planned at 32 weeks gestation and both partners were keen to help produce milk for the twins. The healthy non-pregnant partner was seen at 18 weeks and she had no significant medical history. The suggested timeline for lactation induction is shown in Figure 1. She began the COC as her period had just finished and there was no chance of pregnancy. One week later, she commenced domperidone 10mg i tds, and increased to ii tds after another week. Four weeks prior to the planned birth, she stopped the COC and began expressing manually. By the time of birth, the non-birth mother was expressing 20 mL per expression; up to 140 mL per day. Twin boys were born at 32 weeks and the birth mother commenced breastfeeding/expressing with the infants in special care nursery. The non-birth mother was expressing 50 mL per expression. Both infants were exclusively breastmilk fed for five weeks while in hospital. Both mothers breastfed both infants, often alternating infants each feed. The couple provided this quote for our poster presentation: ‘Induced lactation allowed us to have a supply of breast milk stored for when the boys arrived. Induced lactation also enabled us both to breastfeed and was a perfect way for both of us to bond with our twins.’12

Figure 1. Plan for induced lactation in non-birth mother showing medicines to simulate pregnancy and then expressing prior to expected date of delivery of monochorionic twins.

In contrast, a recent referral from the neonatal service for a same-sex couple was a different scenario. The birth mother was struggling with low milk production and staff suggested her partner might be able to help. However, the nonbirth mother was aged 45 years, had never been pregnant, and lived with several physical and mental health conditions requiring medications not compatible with domperidone. Following an explanation of the process of inducing lactation and after discussion, the couple did not proceed with this. The couple were encouraged to focus on supporting the birth mother to increase her supply, rather than add an extra stress at the time.

We have had seen many successful outcomes such as the case of a woman with premature menopause who was able to almost exclusively breastfeed her infant born through surrogacy. Another woman who had a history of thrombosis after hysterectomy and was unable to take oestrogen, successfully induced lactation taking the progesterone only pill in the pregnancy simulation stage.

What next?

Healthcare professionals should be aware of the possibility to induce lactation without a pregnancy. The increase in multi-mother families has led to an increase in awareness within the community of induced lactation as an option. A recent research study found that some couples would have appreciated information on this topic: ‘I wish we could’ve known (about induced lactation). Because then we really would’ve sat down and said, “Is this something we really want to do?” She (non-gestational partner) really would’ve considered it. It would change the landscape in terms of her work, how much time she got off and all. It definitely would’ve been nice to know a lot earlier.’13

Early referral for specialist assistance is essential; ideally around week 16 of pregnancy. The Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine provides clinical protocols for many breastfeeding issues. A recently published protocol ‘Lactation Care for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Questioning, Plus Patients’ provides some information on induced lactation.14 The Australian Breastfeeding Association has information on induced lactation and relactation to share with families.15

References

- Cazorla-Ortiz G, Obregon-Guiterrez N, Rozas-Garcia MR, et al. Methods and success factors of induced lactation: A scoping review. J Hum Lact. 2020;36(4):739-49.

- Czank C, Henderson JJ, C KJ, et al. Hormonal control of the lactation cycle. In: Hale TW, Hartmann P, eds. Textbook of Human Lactation. Amarillo, Texas: Hale Publishing, L. P 2007:89-111.

- Auerbach KG, Avery JL. Induced lactation. A study of adoptive nursing by 240 women. Am J Dis Child. 1981;135(4):340-3.

- Thearle MJ, Weissenberger R. Induced lactation in adoptive mothers. ANZJOG. 1984;24:283-6.

- Gribble KD. Mental health, attachment and breastfeeding: implications for adopted children and their mothers. Int Breastfeed J. 2006;1:5.

- Goldfarb L. Inducing lactation. 2019. Available from: www.asklenore.info.

- Grzeskowiak LE, Smithers LG, Amir LH, et al. Domperidone for increasing breast milk volume in mothers expressing breast milk for their preterm infants: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BJOG. 2018;125(11):1371-8.

- Smolina K, Mintzes B, Hanley GE, et al. The association between domperidone and ventricular arrhythmia in the postpartum period. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2016;25(10):1210-14.

- Brodribb W. ABM Clinical Protocol #9: Use of galactogogues in initiating or augmenting maternal milk production, Second Revision 2018. Breastfeed Med. 2018;13(5):307-14.

- The Royal Women’s Hospital. Clinical Practice Guideline: Medications and herbal preparations to increase breastmilk production, 2020. Available from: https://thewomens.r.worldssl.net/images/uploads/downloadable-records/clinical-guidelines/infant-feeding-management-of-low-breast-milk-supply_280720.pdf.

- Kirkman M, Kirkman L. Inducing lactation: a personal account after gestational ‘surrogate motherhood’ between sisters. Breastfeed Rev. 2001;9(3):5-11.

- Moorhead AM, Amir LH. ‘Can I breastfeed without being pregnant?’ Case studies of induced lactation (Poster). J Paediatr Child Health. 2012;48(Suppl 1):104.

- Juntereal NA, Spatz DL. Same-sex mothers and lactation. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2019;44(3):164-69.

- Ferri RL, Rosen-Carole CB, Jackson J, et al. ABM Clinical Protocol #33: Lactation care for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, questioning, plus patients. Breastfeed Med. 2020;15(5):284-93.

- Australian Breastfeeding Association. Relactation and induced lactation, 2020. Available from: www.breastfeeding.asn.au/bfinfo/relactation-and-induced-lactation

Leave a Reply