When Talei Morrison, a prominent and respected Māori kapa haka performer, was just 41, she was in Rotorua Hospital supporting a whānau (family) member who was having treatment, when she started to bleed profusely herself. She went to the emergency department and was subsequently diagnosed with cervical cancer – a diagnosis that had been missed by her regular doctor.

In just nine short months between this diagnosis and her passing in 2017, Talei put a phenomenal amount of work into Smear Your Mea – a campaign to raise awareness, and to educate and empower wāhine Māori (Māori women) and their whānau about cervical cancer.

Five years on from the campaign’s launch, we sat down with Talei’s mother, Prof Sandy Morrison, who is continuing to champion her daughter’s Smear Your Mea legacy.

On unconscious bias in the medical system

Talei had been visiting her family doctor for 11 years, being continually diagnosed with a urinary tract infection, without it being flagged that she hadn’t had a pap smear in that time.

Prof Morrison wonders, “How can you misread flags like that? When do you stop and say, ‘This is not right?’ That was my shock, that Talei said she was again [mis]diagnosed, and yet she was saying to her doctor, ‘I feel like there’s something there, and it’s really impacting me.’ Where we have incredible disappointment is that there was a failure to listen well – and that includes listening to what’s not said. If you’re a doctor who sees your patient regularly, watch out for these signals when you’ve got someone who’s fitting the high-risk factor. Really feel and listen to the spirit of what they’re saying and not saying. Listen to the whānau member who may be with them.”

As Prof Morrison explains, “Talei was highly educated, but in her moment of vulnerability, she didn’t push for herself. Be aware that even the most educated of us will defer to you as the medical expert. Don’t get defensive about your level of expertise – I’m not saying our doctor did, but I’ve been in situations where the doctor does.”

On discovery of cervical cancer, the emergency specialist rang Talei’s doctor and asked why there had been no referral for testing. According to Prof Morrison, “Talei’s doctor said to us, ‘Your ultrasound is going to be far too expensive’ – and it was just a couple of hundred dollars. There was just this assumption [that we couldn’t afford the test]. When Talei was seeing oncology, again, a doctor said, ‘You’ll need this medicine that’s too expensive, it’s going to cost $300,000.’”

Prof Morrison asks, “How do you know we don’t have $300,000? All these assumptions were made about our capacity and our ability. If they didn’t make those assumptions – if they’d just asked ‘Would you like to buy this medicine for $300,000?’, I would’ve said ‘Of course, we’ll have the money to you by tomorrow.’ If they’d have said it’s a couple of hundred dollars for an ultrasound, we might still have Talei here today.”

“I want to say that in this particular circumstance, further investigation didn’t happen when it should have, and multiple clinicians assumed something. As a mother, that’s the really, really painful part for me.”

Smear Your Mea: How it started….

When Talei decided to launch herself into campaign work following her diagnosis, Prof Morrison says, “I responded with caution and horror – all I could see was attention being diverted from her own level of energy to get herself well. But Talei just did her own thing anyway; she felt this was bigger than anybody.”

Prof Morrison admired her daughter’s selfless drive to raise awareness and educate, with a higher-level goal of finding culturally responsive ways to target cervical cancer among wāhine Māori, while also embracing wairua (spirituality).

The name itself took a little bit of thinking: “Te Korowai Aroha Rotorua had kindly confirmed that they were happy for us to use the name. You should’ve seen all the names they’d come up with! Some were very humorous; others were just… not for anybody’s ears! But this one was catchy, it was well-considered, and it had meaning; it made people start to think, ‘What is this?’”

In Talei’s kapa haka world (kapa haka is the expression of Māori culture through dance and song), her fellow performers got behind her, and they leveraged her cultural platform to launch the campaign. Word spread quickly and in no time they had television coverage. Talei was doing interviews and appearances, and it had a rippling impact.

Prof Morrison and Smear Your Mea campaigners with

then-Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern

As the campaign gained momentum, more health clinics began requesting to work with communities on the ground. The group set up at kapa haka festivals, sports events and other places where Māori people gather. By simply talking and listening, they were amazed to learn the number of people who didn’t have a smear because they found going to medical clinics a very frightening experience.

The Smear Your Mea information tent set up

wherever Māori come together

Prof Morrison says, “Because we’re only a very small charitable trust, and everyone’s got limited capacity, we had to really target where we invested our energy. For Talei, it started with the regional kapa haka festivals, but then Te Matatini (Aotearoa’s national kapa haka festival) came on board, and through the advocacy work of Te Ururoa Flavell (Former Minister for Māori Development), and the whole whānau, it opened up another avenue where the campaign could have an impact at a higher level.”

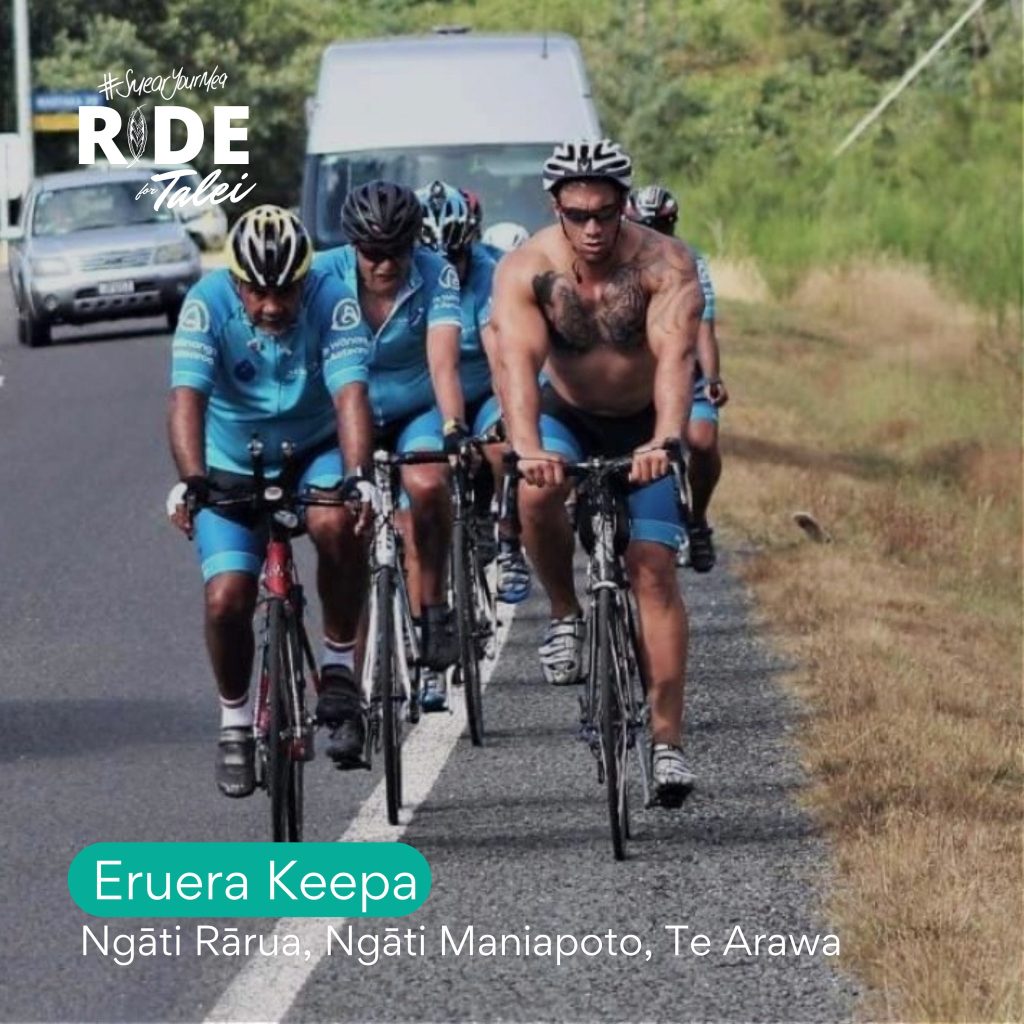

And that’s how the Ride4Talei charity bike ride was born. As Prof Morrison explains, “Te Ururoa and Talei were very close, and he promised her before she passed that, ‘I’m going to do as much for you [as I can]’ – and suddenly he was off just doing it! Finding sponsorship and publicity. It was amazing because the ride meant that we could carry our health message into communities, and promote the fact that we need to be more holistic in looking after our health – that we all, as whānau, need to take responsibility for our whānau members; that when it comes to cervical cancer, and talking about our ‘private parts’, the only way that we are going to increase the numbers [of people getting screened] is to actually talk about it, and not be afraid of those conversations. To make sure that we share what we are doing with our families, and that our families encourage that.”

Te Ururoa Flavell (front left) and Talei’s brother Eruera

Keepa (front right) leading the ride

Prof Morrison continues, “It gave us access to a whole group of people just through that ride, who started to ask very searching questions, or who would reveal to us past experiences, or anxieties in the present, or looking for help and support – it was such a privilege to visit so many Māori communities and health clinics who showed very genuine and heartfelt manaaki (hospitality, support) to us on that tour. We were thrilled to complete the ride for the pōwhiri (opening ceremony) for Te Matatini, and then be part of the Mana Wahine Collective who set up a clinic for us to educate and do smears – we got close to 50 smears during those three or four days of Matatini, for wāhine who might never have gone into their doctor due to fear. So that was an awesome achievement.”

Prof Morrison and those on the ride were able to connect with community members from a place of mutual understanding, creating a safe environment for them to open up. “I was honoured to be privy to all their stories, and hear all of their concerns,” she says. “I’m educated, and I’m not afraid to ask questions or to challenge and advocate for others – what a privilege to still hear the concerns that many of our Māori whānau have.”

… and how it’s going

As her health declined, Talei began to consider the future of the campaign and said to her mother, “Well you’re Māmā Mea, you make the decision.” In reply, Prof Morrison joked, “I don’t want to be Māmā Mea! I’ve got my own life!” But in hindsight, she considers her increased involvement quite serendipitous: “I’m a busy academic, and [my work] has taken a bit of a turn towards the health sector to pay tribute to Talei’s work. We had some of my Masters students do an evaluation report. I’m very interested in what research we can do, and I’d really like to give that more attention with other health professionals, on how Smear Your Mea can help, so that I’ve got evidence-based research to help inform our direction forward.”

After the Ride4Talei, Prof Morrison considered bringing the campaign to a close on a high note. But she was met with protest from the whānau, and Te Korowai Aroha, and other Māori practitioners and health agencies who said, “No, please don’t – the reaction we’re getting is really positive!” And so Prof Morrison was convinced. “It’s encouraging a lot more women to be able to go and have their cervical smears,” she says. “So that’s why we’re still here and we’re about to embark on another Ride4Talei [in February 2023]!”

In recognition of the month Talei received her diagnosis, the campaign marks national Smear Your Mea day on 30th August each year. Prof Morrison says, “We didn’t know the date was right before cervical cancer month – it was just incredibly opportune! And the number of people who want to use the Smear Your Mea campaign to help that month has been incredible.”

Looking to the future, Prof Morrison says, “We don’t want to age the campaign and make it stale – but health inequity is a huge issue, and Māori women still feature disproportionately in all of those numbers. Hence it is normalised – and we don’t want to see cancer normalised. I think as long as there’s inequity, which is going to be a forever job, we’re going to have to exist.”

“But it’s thinking about a more innovative way of existing, and finding ways to get the message across, which may include technology, and champions other than us. The Trust still says it’s kapa haka – Talei’s focus was kapa haka – so reigniting every kapa haka amongst groups. That’s why we thought we’d do it again, [especially as] we had the long break with the pandemic and no Matatini, so in many ways it’s still fresh.”

Recently, Te Ururoa’s daughter – through her popular clothing label, Hine – designed the ‘Poi-Gal’ dress in honour of Talei, and generously supported the campaign with funding and merchandise.

Of their RANZCOG Māori Women’s Health Award, Prof Morrison says, “The College is such a well-established, reputable organisation that embraces clinical practice, as well as culturally responsive strategy. So that meant a lot for us – that we’re not just a community group over here [in Aotearoa], but that the College acknowledged our work from a clinical perspective as well. When you win these awards, and when people give you all this support, you think, ‘Well, I guess we’re going to carry on!’

Smear Your Mea has been widely awarded and recognised, as follows:

- RANZCOG Māori Women’s Health Award (2020; image below)

- Matariki award (2019)

- Support from Makau Ariki Te Atawhai, the Māori King’s wife

- Continued support from Te Korowai Aroha (ahead of the formal handover of the name)

- Leadership from Te Ururoa Flavell, including support, resources and promotion

- Backing from Trust members and their whānau

(Left to right): Dr Kasey Tawhara, Te Ururoa Flavell, Nadine Riwai, Prof Sandra Morrison, Elaine Kameta, Tiria Waitai, Eruera Keepa.

On working with government to improve outcomes

Since the introduction of the Māori Health Authority in July 2022, Prof Morrison is hopeful that the Trust can work side-by-side with the Ministry of Health for the benefit of wāhine Māori, after a previously fractious relationship. “We don’t know what that relationship looks like,” she says. “We’ve certainly put out feelers on how we can work together. And there was the enquiry into Māori health; we were in a position to have substantive input into that, and therefore we made a submission.”

Additionally, Eruera Keepa – a key leader of Smear Your Mea – has had conversations with Riana Manuel (CEO of the Māori Health Authority). Eruera also happens to be Prof Morrison’s son and Talei’s brother.

Prof Morrison also says, “We’re lucky to have Nadine Riwai (Senior Portfolio Manager, National Cervical Screening Programme at Ministry of Health New Zealand) and Dr Kasey Tawhara (FRANZCOG) working with us in that space, particularly identifying HPV and self-testing as something specific for us to target.”

“We’re aware that lots of people pick up on Smear Your Mea, and that it’s catchy. We did start talking about intellectual property, but we’re a bit ambivalent – there’s this common kaupapa (topic, purpose), and in the end, you want women smeared, and you want to know that they’ve taken action with their whānau. So that’s going to be a continual balance.”

Having relied on donations to come this far, Prof Morrison says that a more formal relationship with the Māori Health Authority could be very helpful to secure funding for more resources to spread the message to a wider audience: “We don’t have things like those little pins that organisations put out for breast cancer, but we have ideas on putting out poi (a form of dance) with a message, something that’s really strongly kapa haka. We’re hopeful that we could make quite substantive plans, and all work towards the common end that the Māori Health Authority wants as well.”

Prof Morrison notes that there’s more work to be done when it comes to culturally responsive strategies, and points to the COVID-19 response as an example. “Te Puni Kokiri (the Ministry of Māori Development) asked us to give the key success factors for the work with Smear Your Mea, and we did that willingly,” she says. “We saw a lot more targeted campaigns coming from the pandemic, including kapa haka with COVID-19, so we know that the way that our campaign was run has resonance with people who wanted to reach Māori communities. I don’t want that to be lost. It seems so natural to think about who your communities are, and think about a way to respond.”

“Have conversations with your whānau and friends about each other’s health and keep those conversations up.

Respect your role as a kaihaka [performer]. Respect kapa haka; the art form that creates discipline, teamwork,

commitment and that entices passion, energy, and power, because you never know when your last stand will be.”

– Talei Morrison [from the Smear Your Mea Facebook page]

A message to women’s health professionals

If you work in women’s health, what can you do to help? Prof Morrison encourages a firm commitment to incorporating mātauranga Māori (Māori knowledge, wisdom, understanding, skill) into your clinical practice.

“It doesn’t matter if we’ve got the Māori Health Authority; whānau should be involved in decision-making, and we’re quite capable of supporting our whānau. Even in our discussions with whānau, I just hear all the time about so many whānau that just agree, don’t advocate for themselves, and think that the doctor’s the expert. Clinicians have to be really, really active in that space when you’re with whānau – and I know that limited appointment time is against you, but really reach out to see what whānau think, feel, and can support, because it’s absolutely critical in any space. That’s incredibly important to us.”

“I think that we all need to work together, be aware of what’s happening, and leverage off each other’s expertise. The complexity of health issues requires a whole lot of clinician knowledge, whānau knowledge, local knowledge; their whānau must be included.”

Prof Morrison concludes: “Since Talei has passed, we have had 14 children born into our whānau. Every child that’s born then doesn’t have their aunty, who would’ve been a guiding presence for all of them. It’s the potential that we’ve lost, because of people’s assumptions. I know that we’re not the only whānau to experience cervical cancer, but we’re certainly using Talei’s platform to highlight some specific errors that were made within that health system.

Our message to women’s health professionals is: don’t make assumptions about our capacity, our capabilities, or our resources. Whānau is networks. We all want our loved ones with us as long as possible and we really, really need your strong guidance and understanding.”

Prof Morrison is Dean, Te Pua Wananga ki te Ao (Faculty of Māori and Indigenous Studies), Te Whare Wānanga o Waikato (University of Waikato).

Follow Smear Your Mea on Facebook: www.facebook.com/smearyourmea/

O&G Magazine thanks Mieka Vigilante (RANZCOG Publications and Media team) for conducting this interview and writing the article.

Our feature articles represent the views of our authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RANZCOG), who publish O&G Magazine. While we make every effort to ensure that the information we share is accurate, we welcome any comments, suggestions or correction of errors in our comments section below, or by emailing the editor at [email protected]. Those pictured have provided consent for their name and image to be included.

Leave a Reply