Nobel Peace Prize recipient (2018), and Congolese gynaecologist Dr Denis Mukwege once said, “Silence is the greatest ally of sexual violence”. Advocacy is crucial for promoting human rights and women’s rights and remains essential in addressing Female Genital Mutilation (FGM), or rather, what this article defends as alternative terminology, Female Genital Cutting (FGC).

Despite ongoing human rights campaigns, FGC/FGM continues to prevail worldwide. The World Health Organisation reports over 230 million girls and women have experienced FGC/FGM in up to 30 different countries1, 2. Girls can be subject to this cruel and painful act as early as infancy to the age of 151. Although progress has been made, FGC/FGM continues with significant physical and psychological consequences to the girls and women affected. Furthermore, the World Health Organisation (WHO) reports up to USD $1.4 billion per year in terms of cost to health systems in providing treatment for the subsequent health complications to victims of this practice1.

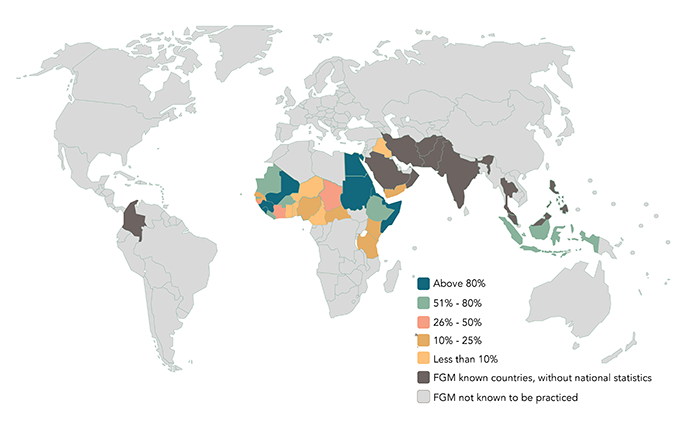

Figure 1 – Percentage prevalence of FGC/FGM Worldwide for girls and women ages 15-49 (WHO FGM Calculator, 2020).3

Language matters, and there is an ongoing shift from using the term FGM to FGC depending on your audience. The United Nations recently rebuked the term “female genital circumcision” as it often draws parallels to cis-male circumcision and negates the far more serious and harmful psychological and physical implications of this practice4.

“Mutilation” reinforces the severity of the practice; yet communities that practice FGC may find this word offensive in that it implies their intent was malicious when that may not be the case. Another reason is that using FGC in reference to individuals and their bodies, may result in decreased engagement from affected communities and individuals. As a result, many organisations utilise both terms simultaneously – FGC/FGM, with FGC being used when speaking to patients, whilst FGM is often used in literature4.

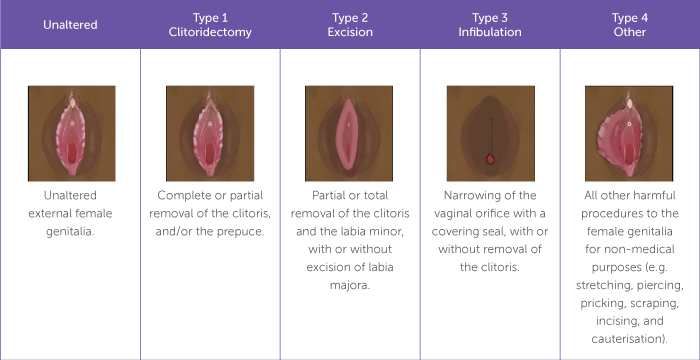

There are four types of FGC/FGM categorised according to the anatomical structure that has been affected (Figure 2)5.

Figure 2 – Types of FGC/FGM.5

There are no supported health benefits to FGC/FGM, only significant physical harm to girls and women both short- and long-term.

These include:1

- Pain

- Swelling

- Bleeding

- Acute and recurrent vaginal and urinary tract infections

- Death

- Difficultly with urination

- Dysmenorrhea

- Keloid scarring

- Dyspareunia

- Childbirth complications including the need for caesarean section

- Excessive tearing/bleeding

- Perinatal mortality

Women frequently require multiple surgeries both before and after childbirth or for deinfibulation. The mental health impacts can result in lifelong post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, and anxiety1.

It is important to recognise that FGC/FGM is an illegal practice in Australia and individuals will be prosecuted if they intend to take their daughters overseas to facilitate these practices6. Nevertheless, there is hope for victims of FGC/FGM to receive deinfibulation treatment for women experiencing physical symptoms pre-conception or in the antenatal period, along with psychological support and counselling.

In some countries, medicalisation of FGC/FGM occurs due to a belief that performing the procedure with a medical practitioner under sterile conditions may reduce risks, and complications, although there is no evidence for this. Those who offer medicalised FGC/FGM attempt to legitimise the practice either for financial incentives or to support existing social beliefs/norms7.

Why does this practice persist and where did it originate? These are questions I recently explored. As I dove further into my reading, I discovered its history stems beyond ideologies of fertility, preservation of virginity, and patriarchal control over women’s bodies8. Its roots were explored by Professor Sada Mire, an archaeologist, and professor of Heritage Studies at University College London in her book entitled, “Divine Fertility.” Her research exposes cultural traditions predating sexual control of girls and women, rooted instead in practices reflecting divine sacrifice. She argues that societies deeply linked the practice of FGC/FGM to the many rituals females experienced as they progressed through the stages of life (just as males did in their own stages), citing carved archaeological evidence of images and symbols to support this theory. She explains that the practice is deeply rooted in Indigenous cultural beliefs if not adhered to, resulted in communities shaming individuals for abandoning their culture and angering the ancestors resulting in curses manifesting as drought, lost crops, and livestock and medical illness9.

The intent to control girls and women’s bodies and sexuality appears to be a secondary rationale that developed over time. To demystify this practice, and advocate against it, it is important to understand this background. Professor Mire argues that introducing alternative practices to FGC/FGM which allow for the cultural blessings of the ancestors whilst denouncing the practice of cutting, can engage more communities and change outcomes for girls/women9.

An alternative rite of passage (ARP) was initially championed in Kenya by a Women’s Development Organisation, Maendeleo Ya Wanawake (MYWO) and Programme for Alternative Technology in Health (PATH). Interestingly, they commenced with educational programs for parents and girls alike which faced resistance as parents still feared shame if they did not participate in FGC/FGM practices10. Their program developed into an alternative rite of passage, allowing families to support their daughters to transition from girls to womanhood, while including the public religious rites, and courses covering content such as reproductive anatomy, dating and marriage, pregnancy and contraception, sexually transmitted infection prevention, empowering young women to feel more informed and families to abandon FGM/FGC through seeing its lack of benefits10. The key is to honour and respect cultural practices while effectively campaigning against FGM/FGC.

There are multiple studies currently exploring the effectiveness of ARPs, and collating data which have been adopted by many NGOs. One major challenge in Kenya is even within specific communities there are obvious nuances. There was reduced uptake amongst Maasai Peoples as the rituals tend to be less public in nature and involve the immediate and extended family. Consequently, ARPs must be thoroughly researched and tailored specifically to individual community needs to ensure effectiveness 10. In addition to ARPs, ensuring local legislation is in place and is enforced can also assist in reducing rates of FGC/FGM.

Currently, numerous organisations and NGOs strongly advocate and lobby for legislative reform.

From writing to political leaders to implementing ARPs within communities, conducting research and collecting data on outcomes for girls, women and neonatal and obstetric outcomes.

The United Nations recently celebrated “International Day of Zero Tolerance for Female Genital Mutilation” on 6 February 2025. The United Nations announced its commitment to ending FGC/FGM by 2030, noting the ongoing decline of the practice in the last 30 years, and that today a girl is one third less likely to experience FGC/FGM. They released a 2023 annual report on joint initiatives by organisations, both global and grassroots, to reduce the rates of FGC/FGM11.

Like many aspects of clinical practice, continued professional development can assist in providing care to women and girls affected by FGC/FGM. The most recent update of the RANZCOG Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting (C-Gyn 1) provides clinicians with a comprehensive, evidence-based resource outlining obstetric considerations for women affected by FGC/FGM. The College also provides a learning module on FGC/FGM in its education platform, Acquire12. True Relationships and Reproductive Health, a profit-for-purpose organisation provides a publicly accessible online course which enables capacity building for healthcare professionals around treating women with FGC/FGM in their clinical practises, including approach, cultural sensitivity, and support12.

Further research into alternative rites of passage and their effectiveness will be essential to determine their potential impact on reducing FGC/FGM rates. Ongoing education, understanding and advocacy are crucial. As healthcare professionals, providing culturally sensitive healthcare can significantly assist women and girls affected by this FGC/FGM, and help break the cycle of this practice, empowering the future generation of young women.

References

- World Health Organisation. Female Genital Mutilation. Updated March 2021. Accessed March 10 2025.

- Equality Now, the End FGM European Network and the US End FGM/C Network. Global Response Report. Updated 2025. Accessed March 10 2025.

- WHO FGM Calculator. Updated 2020. Accessed March 10 2025.

- United Nations Population Fund. Female Genital Mutilation – Frequently Asked Questions. Updated February 2020. Accessed March 10 2025.

- Esse I, Kincaid C.M, Terrell C.A., Mesinkovska N.A Female genital mutilation: Overview and dermatologic relevance. JAAD International. 2024; 14 (92-98).

- National Education Toolkit For FGM/C Awareness. Australian Law. Updated 2025. Accessed March 10 2025.

- United Nations Population Fund. Brief on the medicalization of female genital mutilation. Updated June 2018. Accessed March 10 2025.

- Llamas, J. Female Circumcision – The history, the current prevalence and the approach to a patient. Updated April 2017. Accessed March 10 2025.

- Mire S. Divine Fertility The Continuity in Transformation of an Ideology of Sacred Kinship in Northeast Africa – 1st Springer, Cham. Nov 2022.

- Van Bavel H. The ‘Loita Rite of Passage’: An alternative to the alternative rite of passage?. SSM – Qualitative Research in Health, Dec 2021. Vol 1,100016, ISSN 2667-3215.

- United Nations Population Fund. 2023 Annual Report of FGM Joint Programme: Addressing Global Challenges with local solutions to eliminate female genital mutilation. Updated Aug 13 2024. Accessed March 10 2025.

- Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting – Clinical Guideline. Updated March 2023. Accessed March 10 2025.

Leave a Reply