You’re in a consult with a 14-year-old girl, accompanied by her mother. The young patient describes experiencing cyclical, severe dysmenorrhoea. She is lethargic, her school grades are slipping and she takes days off school to lie in bed with a heat pack and takes paracetamol and ibuprofen, which provide only slight relief. She has dropped out of her sports team due to ongoing fatigue and has missed many training sessions.

Her mother interjects, “I tell her it’s just what periods are like. They were exactly the same for me. She needs to stop using the same excuse over and over again to miss school!”

Sound familiar? You are not alone.

Introduction

One in seven (14%) females and those assigned female at birth in Australia are now estimated to live with endometriosis, an increase from the previously quoted statistic of one in nine (11%). While diagnosis rates are rising, it still takes at least 6-8 years from symptom onset to diagnosis. The additional challenge to this disease is that the degree of symptoms does not necessarily correlate with the severity of disease.1 Heavy, painful cycles and cyclical irregularity are part of the picture in this cohort, and treating these generally is the first important step in acknowledging and validating the suffering associated with menstruation2, and possibly mitigate disease progression.3

Endometriosis is a chronic, inflammatory, gynaecologic disease marked by the presence of endometrial-like tissue outside the uterus. It is increasingly recognised in adolescent populations. While some are asymptomatic, some have a significant impairment in quality of life due to chronic pelvic pain, dysmenorrhoea, and potential impact on their future fertility. The approach to diagnosis and management in adolescents must be tailored, considering their developmental stage, family history, and long-term implications.1

While the exact cause(s) of endometriosis remains unknown, several theories exist:

Retrograde Menstruation

Endometrial tissue refluxes through the fallopian tubes into the pelvic cavity during menstruation. This theory is particularly relevant in adolescents who often experience anovulatory cycles with unopposed estrogen leading to a thickened endometrial lining. Coupled with anatomical maturation, the uterus is still growing and the cervical os is narrow and tight. During menstruation the pressure of the menstrual egress through the very narrow cervical os increases the risk of reflux.4

Genetic Predisposition

Endometriosis appears to run in families, suggesting a genetic component to the aetiology. If a patient has a close female relative with endometriosis, their risk is up to seven times higher.1

Immune Reaction

Antibodies targeting endometrial cells can be found in blood which can lead to an immune response and inflammation in the affected areas, damaging surrounding tissues. However, it is still unclear whether this immune change causes endometriosis or is a response to endometriosis already present in the body.

Coelomic Metaplasia

Cells in the pelvic peritoneum, ovaries, rectovaginal septum, bladder and bowel share the same embryonic origin as endometrial cells. Under specific circumstances, they may transform into endometrial cells, hence becoming endometriosis.

Diagnosis in Paediatric and Adolescents

History and examination

H – Home

- Who is at home with them?

- Do they have siblings? Do they get along with them?

- If they have older sisters, do they have similar issues?

E – Education/Employment

- What year in school are they?

- What school?

- Have they got good friends at school?

- Do they enjoy school?

- Are they experiencing bullying?

A – Activities

- What do they like to do for fun?

D – Drugs (including alcohol, tobacco, vaping)

S – Sexuality

S – Safety/suicidality/depression

Adolescents often require a different approach to consultation compared to adults. Establishing rapport and creating a safe environment for the patient and their family can often change how the rest of the consult continues and how accepting they are of your recommendations. Rather than immediately focusing on the presenting complaint, beginning with a structured psychosocial assessment, such as the HEADSS assessment can help clinicians better understand the patient’s context and family dynamics. This sets the tone for a more effective and collaborative consultation.

As part of the initial consult and good history taking, it is also important to consider other causes for pelvic pain and to do investigations as appropriate.

Pelvic and abdominal pain, urinary discomfort or pain with bowel motions, are common in this age group and taking a detailed history around symptom exacerbation or change during menses is key. It’s important to establish whether pain is actually related to menstruation or indeed bowel or bladder related. Often, and particularly with heavy menstrual bleeding which is a frequently associated symptom with pain, bladder and bowel discomfort is from retrograde menstruation. Management of heavy menstrual bleeding often alleviates pain in most adolescents.2 Retrograde menstruation within this setting in the first five years with anovulatory cycles following menarche is a significant contributor to pain and distress within the paediatric and adolescent age group. Recognising that much of the distress is due to anovulation from an immature hypothalamicpituitary axis function and not necessarily a pathologic cause is vital to appropriate management.

The Role of Early Diagnosis

Early diagnosis and initiating treatment and management is important to mitigate disease progression and alleviate symptoms.3 In adolescents, symptoms may be non-cyclical or subtle, requiring a high index of suspicion. This is not limited to patients with chronic pelvic pain unresponsive to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or hormonal therapy.

Non-invasive tools such as pelvic ultrasound and MRI have moderate sensitivity and high specificity in early or superficial lesions, but high sensitivity and specificity for endometriomas. While transvaginal ultrasound is highly specific for most locations and depths, this may not always be applicable to the paediatric and adolescent age group.

Transabdominal ultrasound is then the recommended imaging modality.5 If a young patient is intellectually impaired or unable to tolerate any imaging, this would add an additional layer of complexity. Laparoscopy, due to its invasive nature, should be considered to diagnose patients with suspected endometriosis preferably after a treatment trial, despite negative imaging. Biomarkers and novel imaging modalities are under investigation but are not yet routine, and not recommended.3

Examination would usually only include an abdominal examination in the paediatric group. However, if an adolescent is sexually active, a pelvic examination could be performed (after discussion and consent) to assess for palpable nodules or pelvic floor muscle spasm.

Management

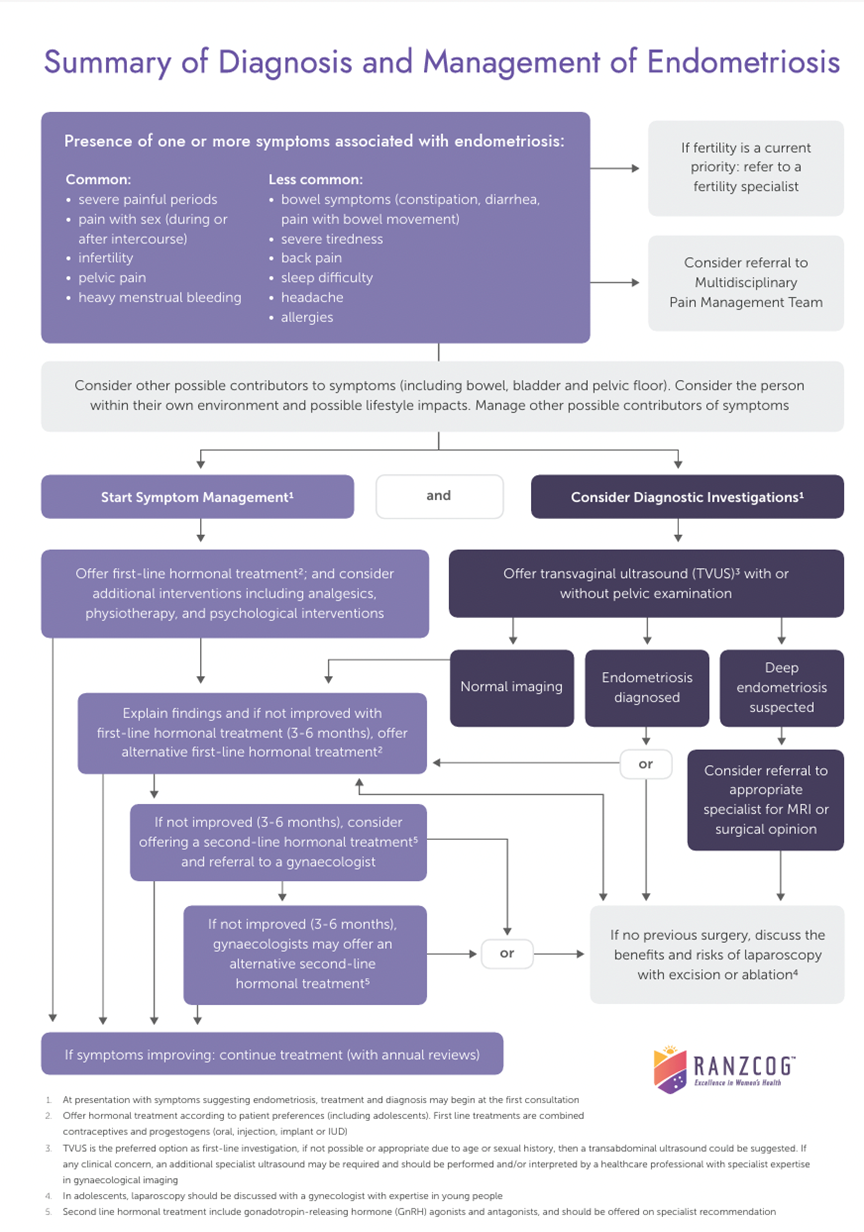

With public waitlists sometimes taking up to a year for patients to be seen, the modified flowchart above is a useful starting point for the management process.6

Imaging is recommended to rule out any outflow tract obstructions, with initial ultrasound, followed by MRI if a Mullerian anomaly is identified. This is important to consider in cases of primary amenorrhoea, or in adolescents who have reached menarche but have worsening cyclical pain, as there could be a mullerian abnormality with a unilateral outflow obstruction.7

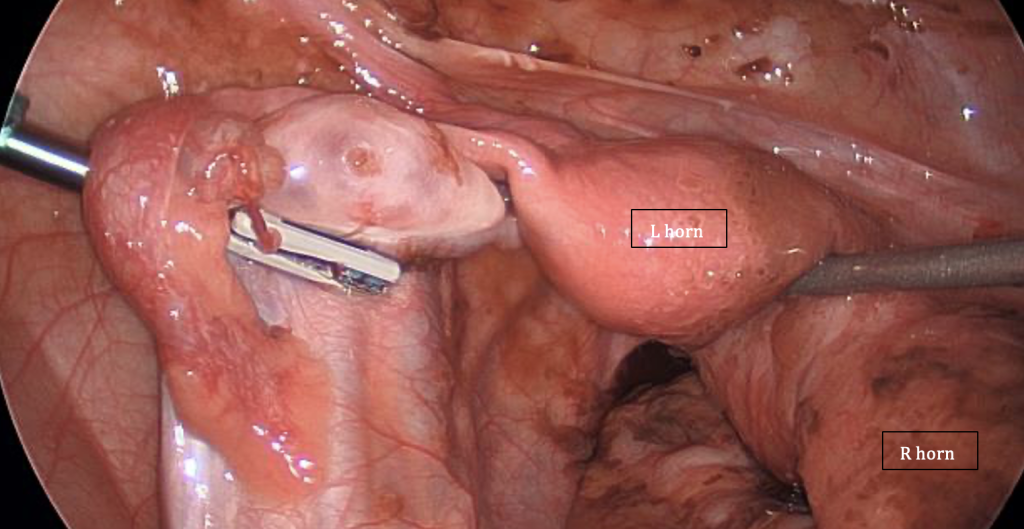

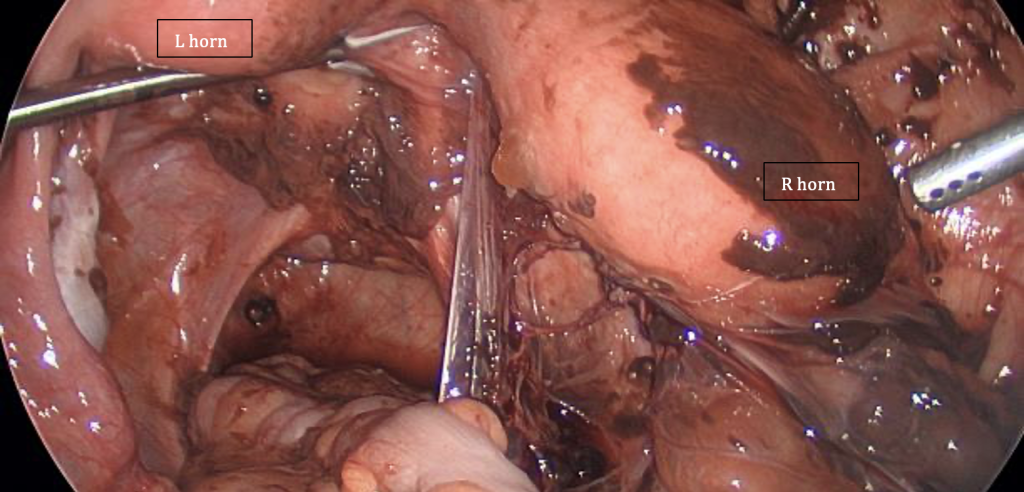

The images on page 55 were taken during a laparoscopy in a 16-year-old patient with uterine didelphys, featuring a patent left hemivagina but an obstructed right hemivagina. There is also ipsilateral right renal agenesis. The photos demonstrate the damage retrograde menstruation from the obstructed side can cause, compared with the unobstructed side of the pelvis.

Medical or surgical treatment may relieve symptoms. However, if pain persists despite treatment, it could be the way the brain is processing the pain. As such, early referral to a local chronic pain service can help patients manage pain flares more effectively and reduce emergency presentations.

Medical Management

There is no known way to prevent endometriosis. Enhanced awareness, early diagnosis and management may slow or reduce the long-term impact, but no cure exists.8 Hormonal therapies aim to suppress the growth of endometrial cells and stop menstruation.9 Treatment should be tailored to the patient’s age, symptom severity and duration of symptoms.

Non hormonal medications

- NSAIDs: Preferred first line analgesics for dysmenorrhoea. While often insufficient alone, effective pain relief can be achieved with appropriate dose and frequency. No single NSAID is proven to be superior. If menses can be predicted, NSAIDs can be commenced 1-2 days prior.10

It is important to reiterate to our young patients and their families that analgesia is important for pain relief but that there is no evidence to suggest that analgesics influence disease progression.11

Figure 1: Distended right uterine horn as a result of the obstructed right-hemivagina, retrograde menstruation and extensive adhesions, dilated fallopian tube and endometriotic lesions. Image courtesy of R Kimble

Figure 2: Patent left uterus and hemivagina, fallopian tube and ovary – notice the absence of any adhesions and minimal impact compared to Figure 1. Image courtesy of R Kimble

Hormonal medications

- Progestogens: Administered orally, by injection or via implant/intrauterine device. They are effective for anovulation by opposing estrogen by downregulating endometrial estrogen receptors, thereby reducing glandular proliferation and inducing endometrial atrophy12

- Tablets:

- Medroxyprogesterone (Provera®) is well tolerated and effective. If normal BMI, recommend 20mg Provera daily continuously to achieve menstrual suppression, or cyclically with a seven day break every 1-3 months. Dose can be adjusted according to response and BMI

- Drospirenone (Slinda®) may be considered if contraception is required

Disadvantage: requires daily adherence and ability to swallow tablets.

- Injectable: Depo-Provera® has benefits of reduction of blood loss and dysmenorrhoea, often achieving amenorrhoea by one year in 50% of users, and is also an effective contraception.

Disadvantage: requires intramuscular injection every 12 weeks. Long term use could result in bone mineral density reduction (which is reversible following cessation)13 - Progesterone releasing intrauterine device: Levonorgestrel IUS eg: Mirena®: Reduction in dysmenorrhoea, effective contraception. 70-95% reduction in menstrual blood loss and achieves amenorrhoea in 54-59% of users.

Disadvantage: Often requires general anaesthetic for insertion in adolescents and does not eliminate ovulation. Ensure uterine cavity is adequately grown to accommodate the device by organising an ultrasound scan to assess uterine cavity length (internal fundus to internal os) before attempting insertion.4 - Combined Oral Contraceptive Pill (COCP): Effective in suppressing ovulation and menstruation. Pill packets can be taken continuously by skipping the sugar pills. It can result in 40-50% reduction in blood loss and is an effective, non-invasive form of contraception.

Disadvantage: increased risk of venous thromboembolism, and it is unclear whether the risk is increased in adolescents who are immobile, as there is insufficient data available. It can also interfere with enzyme-inducing antiepileptic drugs. The additional estrogen of the OCP may be counterproductive to attempts at estrogen down regulation. - Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists (GnRH): Reserved for refractory cases due to potential bone density loss, often paired with add-back therapy.

- GnRH antagonists and aromatase inhibitors: This is still under evaluation in adolescents; concerns exist about long-term effects.14

Treatment should be individualised, considering efficacy, side effects, patient preferences, and impact on bone health.

Surgical Management

Surgery is considered for patients with persistent or severe symptoms refractory to medical therapy. Laparoscopic excision of endometriotic lesions including cysts provide pain relief and confirm diagnosis. In adolescents, conservative techniques that preserve reproductive anatomy is an important consideration. Recurrence of symptoms associated with endometriosis, and/ or endometriosis lesions is not uncommon; hence, post-operative medical therapy is often recommended.15 Consider adding cystoscopy to the surgical consent as interstitial cystitis (part of painful bladder syndrome) can often be found and is a common cause for pelvic pain which often overlaps with endometriosis symptoms.16 Endometriosis and Future Fertility

The importance of finding endometriosis early lies not only in the relief of symptoms but also in the preservation of reproduction potential and suppression of possible natural disease progression. Infertility can result from endometriosis due to anatomic distortion of pelvic organs and/or the fallopian tubes.17 Given its progressive nature, pelvic pain should be evaluated in an expedient fashion and if diagnosed, should be treated aggressively until childbearing is complete.

Multidisciplinary Approach and Future Directions

Managing adolescent endometriosis may be well supported with a multidisciplinary team including paediatric and adolescent gynaecologists, gynaecologists, pain specialists, psychologists, and physiotherapists. If symptoms include bowel and bladder function, early input from other specialties is ideal. Chronic pain can severely impact mental health, schooling, and social functioning. Psychological support, coping strategies, and education are crucial components of care.18

Research is ongoing into biomarkers, non-hormonal treatments, and strategies for early detection. Increased awareness among primary care providers and school-based education can also help in early identification. Future personalised medicine approaches, considering genetic and molecular profiles, may revolutionise future treatment paradigms.

In summary, managing endometriosis in adolescents requires timely recognition, individualised treatment, and holistic support, validating the young person’s suffering. Medical therapy remains first-line, with psychosocial interventions playing a pivotal role. With ongoing research and education the goal is to predict which patients are at risk for disease progression and infertility, enabling true prevention to become a standard of care.

References

- Endometriosis Australia. Endometriosis Australia [Internet]. Sydney: Endometriosis Australia; [cited 2025 Jul 1]. Available from: endometriosisaustralia.org

- Venables A, O’Brien B, Viswanathan D, Kimble RMN. Is progesterone replacement therapy effective in managing heavy and irregular menstrual bleeding and associated severe dysmenorrhoea in the first few years after onset of menstruation in young girls due to physiological progesterone deficiency associated with nonovulatory menstrual cycles in a still-maturing hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis? Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2022;62:34.

- Australian clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and management of endometriosis (version 9).RANZCOG; Jan 2025.

- Williams M, Bagchi T, Kimble R. Menstrual suppression by Mirena IUD insertion in adolescents with disabilities; using USS measures of uterine cavity length to predict procedural success. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2017;30(2):304.

- Bortoletto, P., P. Romanski, and S. Pfeifer, Müllerian Anomalies: Presentation, Diagnosis, and Counseling. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 2024. 143(3).

- Emans SJ, Laufer MR, DiVasta AD. Pediatric & Adolescent Gynecology. 7th Edition. Wolters Kluwer. 2020. Page 499. Figure 32-20.

- Kimble RMN, Khoo SK, Baartz D, Kimble RM. The obstructed hemivagina, ipsilateral renal anomaly, uterus didelphys triad. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2009;49(5):554–7.

- Horne, A.W. and S.A. Missmer, Pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management of endometriosis. BMJ, 2022. 379: p. e070750.

- . Vannuccini, S., et al., Hormonal treatments for endometriosis: The endocrine background. Reviews in Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders, 2022. 23(3): p. 333-355.

- Brown, J., et al., Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for pain in women with endometriosis. Cochrane Database Systematic Reviews, 2017. 1(1): p. CD004753.

- Hewitt GD, Gerancher KR. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Adolescent Health Care. Dysmenorrhea and endometriosis in the adolescent. Committee Opinion No. 760. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132(6):e249–e258.

- Borzutzky C, Jeffrey J, Diagnosis and Management of Heavy Menstrual bleeding and bleeding disorders in adolescents. JAMA Paediatrics 2020;174(2):186-94

- Leeks R, Bartley C, O’Brien B, Bagchi T, Kimble RMN. Menstrual suppression in pediatric and adolescent patients with disabilities ranging from developmental to acquired conditions: a population study in an Australian quaternary pediatric and adolescent gynecology service from January 2005 to December 2015. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2019;32(5):535–40.

Leave a Reply