In this case, a 51-year-old G1P1 presented with a nine-month history of abnormal uterine bleeding and dysmenorrhoea, as well as cyclical bowel symptoms including painful constipation and tenesmus.

Initially, the woman reported intermenstrual bleeding lasting up to two weeks, which progressed to almost two months of continuous bleeding. Vaginal examinations were not undertaken at the time of initial presentations to primary and secondary care. She presented to the emergency department at a tertiary referral hospital following an acute heavy bleeding episode, provoked by transvaginal ultrasound.

The patient’s past medical history is significant for irritable bowel symptoms, having had a colonoscopy the year prior to presentation which was normal. She had a caesarean delivery and does not take medications. Her gynaecological history is unremarkable, with a prior regular menstrual cycle, no dysmenorrhoea, dyschezia, heavy menstrual bleeding, or other abnormal uterine bleeding. Her cervical screening was up to date and normal.

Speculum examination revealed an irregular mass on the posterior vaginal wall. Digital vaginal examination determined this posterior vaginal wall irregularity was notably separate from the cervix. On rectal examination, a large mass was palpable anteriorly, approximately 6cm in size, but the overlying rectal mucosa palpated normally at a combined recto-vaginal examination.

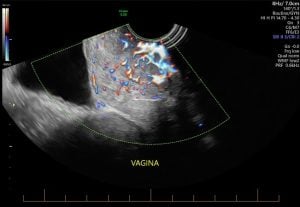

An ultrasound demonstrated an anteverted uterus measuring 10 x 4 x 6cm with features of adenomyosis, and an endometrial thickness of 3.4mm. The ovaries were unremarkable. A hyperechoic lesion measuring 52 x 52 x 36mm appeared to arise from the vaginal wall, with a solid appearance and increased vascularity.

The woman underwent an examination under anaesthesia as a combined case with gynaecology and colorectal surgery. On vaginal examination, the posterior and right lateral vaginal wall was eroded by invasive process, with small volume bleeding and copious debris from this region. On rectal examination, a 5cm mass was palpable, 4cm cephalad to the anal verge, displacing the rectal wall anterolaterally. A flexible sigmoidoscopy did not reveal any mucosal lesion. Vaginal biopsies were taken with histopathology confirming endometriosis.

Following the patient’s diagnosis, medical and surgical management options were discussed. It was advised that surgical management would have conferred significant morbidity, requiring ultra-low anterior resection and a stoma. The patient preferred to avoid surgical treatment, instead choosing initiation of the GnRH analogue Goserelin 3.6mg implant (Zoladex, AstraZeneca Pty LTD). Progress was assessed clinically and symptomatically during follow up visits.

After 6 months of treatment, amenorrhoea was achieved, and there was no longer a discernible mass on vaginal examination. A 1cm region of persistent erosion was also noted on speculum exam without contact bleeding. While she had improvements in the pain and dyschezia, she experienced ongoing faecal urgency and urge incontinence, although the severity fluctuated throughout the treatment duration.

The patient experienced expected side effects such as anxiety, depression, dry eyes and vasomotor symptoms. She ceased employment due to cognitive and mood effects impacting on her function. At her preference, add-back hormone therapy was not used. She was advised to pursue management for her mental health symptoms, facilitated by her primary care provider.

At age 53 years, after 15 months, Goserelin was ceased. An ultrasound demonstrated no recurrence of the rectovaginal disease. Symptoms of faecal urgency and tenesmus increased again, and heavy menstrual bleeding returned three months after cessation. The colorectal surgeons repeated her flexible sigmoidoscopy with abnormal appearance of the rectal mucosa noted, however biopsy did not reveal any abnormality. She was referred for physiotherapy and a further discussion regarding medical management was initiated.

A trial of drospirenone 4mg (Slinda, Besins Healthcare Australia Pty Ltd) reduced the severity of rectal symptoms, however she developed persistent bleeding. After three months she underwent a hysteroscopy where she was noted to have blood and copious debris in the vagina again. Histopathology confirmed recurrence of invasive vaginal endometriosis, with a 4cm palpable mass again evident.

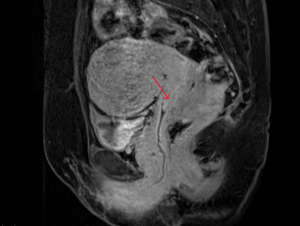

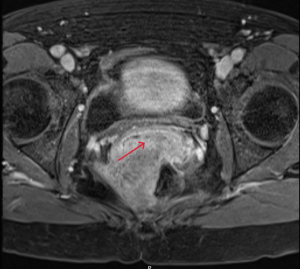

A pelvis MRI with gadolinium contrast was performed which confirmed deep infiltrating endometriotic mass invading the right posterior wall of the vagina anteriorly and the mesorectal fascia posteriorly, with involvement of the levator ani, and direct contact with the rectal wall. She again declined surgical intervention.

Due to recurrence of the rectovaginal lesion and symptoms, it was recommended to recommence a GnRH analogue for medical management. Due to the side effect profile of the patient’s previous treatment, the decision to commence Relugolix/Estradiol/Norethisterone (Ryeqo, Gedeon Richter Pty Ltd) was made. Her bleeding ceased almost immediately with significant improvement in pain symptoms.

She continues to see pelvic physiotherapy for management of ongoing tenesmus, and reports improvement in these symptoms when on treatment and with ongoing physiotherapy. Menopausal side-effects did not recur with Relugolix. She remained symptomatic of mood disturbance and had engaged with psychologists and commenced anti-depressants. At time of writing of this report, she has been on Relugolix for 11 months.

Rectovaginal endometriosis affects up to 37%1 of those with endometriosis. Vaginally invasive lesions are very rare with some reports suggesting a prevalence of 0.02%.2 A holistic approach to treatment options requires consideration of the patient’s symptoms, preferences, and the potential side effects and risks of each option.

This is a case study of a 51-year-old pre-menopausal woman with vaginally invasive rectovaginal disease which was managed medically for over two years. It highlights the importance of thorough investigation of endometriosis patients to identify vaginal and rectal disease with digital and speculum examinations. It also emphasises the importance of care provision via a surgical and allied health multidisciplinary team with experience in endometriosis.

In this case, the patient declined surgical management of endometriosis due to risk. A large case series of 363 women over ten years reports an 8.5% risk of rectovaginal fistula in cases where there has been significant rectovaginal disease resected, particularly less than 8cm from the anal verge, regardless of the formation of a protective stoma.3 In this case, the lesion was lower than this level and the potential morbidity was not acceptable to the patient.

Medical management with progestogens or GnRH analogues are recognised options, and this case highlights the effectiveness of GnRH analogues in reducing the size of deep endometriosis lesions. The side effect profile of GnRH analogues, and arguably of any hormonal suppression, cannot be discounted, as they can impact quality of life. Therefore, treatment decisions should be based on evaluating the most favourable outcomes that are both tolerable and acceptable to the patient.

Pelvic US 1 and Pelvic US 2: Transvaginal pelvic ultrasound at initial diagnosis demonstrating highly vascular hyperechoic lesion

Pelvic US 1 and Pelvic US 2: Transvaginal pelvic ultrasound at initial diagnosis demonstrating highly vascular hyperechoic lesion

MRI 1 and MRI 2: Pelvic MRI after diagnosis of recurrence demonstrating vaginal invasion of deep endometriotic lesion

MRI 1 and MRI 2: Pelvic MRI after diagnosis of recurrence demonstrating vaginal invasion of deep endometriotic lesion

References

- Moawad NS, Caplin A. Diagnosis, management, and long-term outcomes of rectovaginal endometriosis. Int J Womens Health. 2013;5:753–63. doi:10.2147/IJWH.S37846

- Nelson P. Endometriosis presenting as a vaginal mass. BMJ Case Rep. 2018 Jan 23;2018:bcr2017222431. doi:10.1136/bcr-2017-222431

- Roman H, Bridoux V, Merlot B, Noailles M, Magne E, Resch B, et al. Risk of rectovaginal fistula in women with excision of deep endometriosis requiring concomitant vaginal and rectal sutures, with or without preventive stoma: A before-and-after comparative study. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2022 Jan;29(1):56–64.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2021.06.013

Leave a Reply