Visitors to the 1939 World’s Fair in New York were in for a treat. Billed as an exhibition of the World of Tomorrow, the fair stretched over more than 1200 acres, and included giant sculptures, a futuristic cityscape, the world’s first synthetic voice synthesiser, the first fluorescent light and fixture, and Elektro the Moto-Man – a seven-foot-tall walking, talking, smoking and singing robot.1

Fig. 1. King George VI and Queen Elizabeth greet visitors at the 1939 World’s Fair in New York City. FDR Presidential Library & Museum. Source: FDR Presidential Library & Museum. Licensed under CC BY 2.0

Amongst this array of spectacles was an exhibit entitled The First Year of Life. The “brainchild” of Brooklyn obstetrician and gynaecologist, Robert Latou Dickinson, the exhibit was a series of two dozen sculptures (known as the Birth Series) which showed “a neatly progressing narrative of pregnancy, ordered from conception through birth.” As they passed by each sculpture, visitors to the exhibit were offered pamphlets by an attendant which described each stage of fetal development.2 The sculptures were a collaboration between Dickinson, and Scottish sculptor, Abram Belskie. Dickinson prepared sketches and designs that were then modelled by Belskie.

Dickinson and Belskie

Born in 1861, Dickinson was fascinated by the inner workings of the human body from an early age. At the age of ten, he suffered a canoeing accident where he received a horrible gash across his abdomen, after which “with remarkable calm, he swam ashore with one hand, holding his intestines in place with the other.” The village doctor, crippled with arthritis, was unable to complete the required sutures and instead instructed “the local shoemaker” on the process.3 Dickinson was “enthralled” by the doctor’s confidence, and a passion for medicine was born.2

By the time of the 1939 World’s Fair, Dickinson was 78 and had enjoyed a long and successful career in obstetrics and gynaecology. A talented artist, Dickinson used drawing throughout his career as a physician, “complementing each case history with sketches of his patients’ sexual anatomy in which he noted the size, colour, and shape of their genitalia.”4 His methods were, however, not without controversy, as with the advent of photography he also made use of “a well-positioned camera secretly hidden in a flowerpot in his office” to capture images for his clinical notes.4

Whereas Dickinson’s interest in obstetrics and gynaecology was deep and lifelong, the younger Belskie was from a different world. Born in 1907, and raised in Glasgow, Belskie was taken aback on his first encounter with Dickinson and his work. Looking beyond the door of Dickinson’s office, Belskie’s “first impulse was to get the heck out of there… They were painting something to do with genitalia.”4 Fortunately, however, the two men hit it off, and what began with the Birth Series ended up being a collaboration which produced “over one hundred additional medical teaching models in the decade that followed.”4

The World’s Fair

Stephanie Gorton notes that the Birth Series exhibition at the 1939 World’s Fair “was the first time, outside the realm of medical education or a sideshow cabinet of curiosities, that crowds of people had had a way to envision together what a human fetus might actually look like—and it was a sensation.”2 According to Rose Holz, the exhibit “attracted long lines from ten in the morning to ten at night,” and was so successful that “it prompted more than a few complaints from fair organisers and fellow exhibitors,” claiming that the exhibit “prevented people from visiting other booths.” Such was the demand that a second set of sculptures was produced to help get through the queues.

Following the World’s Fair, demand for the Birth Series only increased. Additional copies of the sculptures were made, with medical, public health institutions, and museums all desiring them, as well as commercial companies and even department stores. Creation and transport of the models was, however, expensive and somewhat difficult, and not all who wanted the models were able to obtain them. The solution to this problem was to “reproduce them in a variety of cheaper and more transportable forms.”4 The most successful of these reproductions was the Birth Atlas.

The Birth Atlas

The Maternity Center Association (MCA) (the original commissioners of the First Year of Life exhibit) decided to produce a publication called the Birth Atlas, a book which “depicted the entire Birth Series using photography and line plate drawings.”3 The Birth Atlas was a huge success. Indeed, as Rose Holz notes, it was “more popular than the sculptures themselves,” going “through six editions (with many reprints of each) from 1940 through the1960s.”3

The RANZCOG Frank Forster Library holds a copy of the second edition of the Birth Atlas, printed in New York in 1943. This copy of the Birth Atlas was donated to the College by St George’s Hospital, Kew, forming part of a group of items collected on the hospital’s final day of providing obstetric services in November 1998.

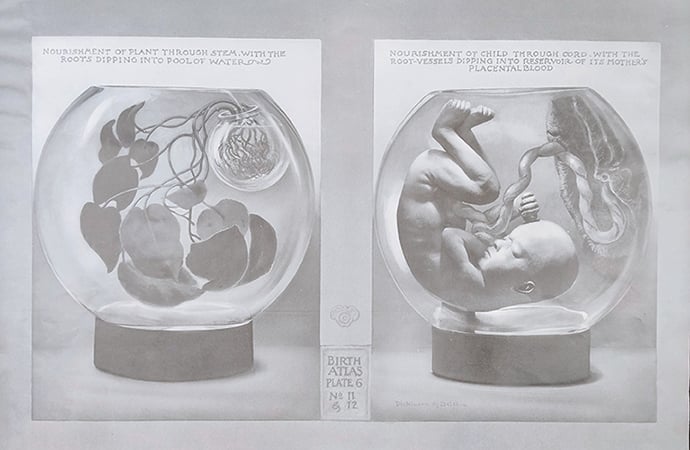

Measuring 45cm wide by 56.5cm in height, the tattered black cover of the atlas contains 16 large scale, “life size” black and white plates. Each plate is given a brief caption, detailing the stage of fetal development depicted. One image in the atlas compares the nourishment of a plant to the nourishment of a baby in the womb, in an attempt to draw a comparison with something the audience was more familiar with. Beautifully detailed, the plates provide a fascinating insight into the models that captivated a curious New York public over 80 years ago.

Fig. 2-4. The Birth Atlas, 2nd edition, 1943. Frank Forster Library collection. Photos: Greg Hunter.

The College is also fortunate to hold a series of six enlarged prints taken from this edition of the Birth Atlas. These prints were part of a subsequent donation to the College by St George’s Hospital in 1999, having previously been used in the hospital’s antenatal clinic. At the time of writing, these prints take pride of place on the wall on Level 4 of Djeembana College Place. Members and trainees are invited to visit the College to view these fascinating insights into obstetrics history.

References

- Rare Historical Photos. Rare pictures from the 1939 New York World’s Fair. Rare Historical Photos. Accessed August 18, 2025. https://rarehistoricalphotos.com/1939-new-york-world-fair/

- Gorton S. At the 1939 World’s Fair, Robert Latou Dickinson Demystified Pregnancy for a Curious Public. Smithsonian Magazine. July 24, 2023. Accessed August 18, 2025. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/at-the-1939-worlds-fair-robert-latou-dickinson-demystified-pregnancy-for-a-curious-public-180982568/

- Simmons FA. Robert Latou Dickinson: An Appreciation. Fertil Steril. 1953;4(1):1-9. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)31141-4

- Holz R. The 1939 Dickinson-Belskie Birth Series Sculptures: The Rise of Modern Visions of Pregnancy, the Roots of Modern Pro-Life Imagery, and Dr. Dickinson’s Religious Case for Abortion. J Soc Hist. 2018; 51(2): 980-1022. doi: 10.1093/jsh/shx035

Leave a Reply