Cytomegalovirus in Pregnancy: Why It Matters

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is a common herpesvirus and the most common cause of congenital infection. In high-income countries, about one in 200 babies are born with CMV1, and approximately one in ten of these infants will develop significant long-term health impacts, including sensorineural hearing loss, developmental delay, epilepsy, and cerebral palsy.2

CMV Transmission and Risk Factors

CMV is transmitted through direct contact with infected body fluids, such as saliva and urine. If a woman acquires CMV during pregnancy, the virus can cross the placenta, infect the fetus, and cause significant complications including fetal brain damage, hydrops, anaemia, stillbirth, or neonatal death.

Children under three years of age are common sources of infection because they can shed large amounts of virus in their urine and saliva for up to two years after initial infection3. People who work with or care for young children (e.g. parents of toddlers, or childcare workers) are at increased risk of infection through direct contact with infected secretions. Healthcare workers who practice universal precautions are not at increased risk of CMV infection.4

Primary CMV Infection

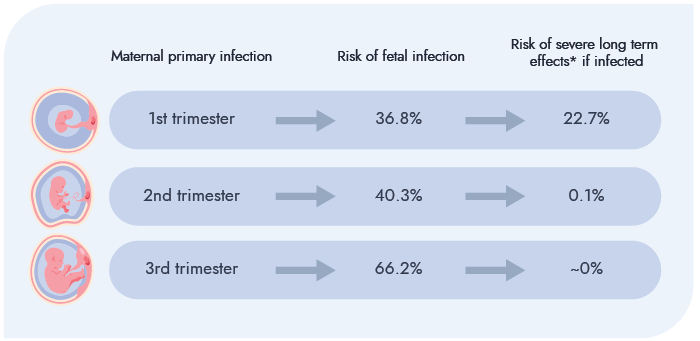

Primary CMV infection during pregnancy (i.e. infection in a previously seronegative woman) carries the greatest risk of fetal transmission. The greatest risk of severe fetal/newborn complications is associated with maternal primary infection in the first trimester.5 (Figure 1)

In Australia, approximately 40% of women of childbearing age are CMV seronegative and therefore susceptible to primary infection during pregnancy. Maternal seroprevalence is most strongly predicted by country of birth: women from high income countries, such as Australia, are more likely to be seronegative.6

Figure 1. Risk of fetal infection and consequences following maternal primary infection⁵

*sensorineural hearing loss or neurodevelopmental impairment NB: If maternal primary infection occurs in the periconception period (from 4 weeks pre–last menstrual period (LMP) to 6 weeks post–LMP), there is a 21% risk of fetal infection with a subsequent 28.8% risk of fetal and/or newborn complications. However, there is insufficient data to estimate long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes in this group.⁵

Non-primary CMV Infection

If a pregnant woman with pre-existing CMV IgG antibodies becomes reinfected with another strain of CMV or has a reactivation of latent CMV, this is called non-primary infection. While the risk of fetal transmission is much lower (1-2%) after maternal non-primary infection, the fetal consequences can be just as severe as after primary infection.7 Non-primary infection cannot be diagnosed on maternal serology alone and is usually a retrospective diagnosis, after identification of fetal ultrasound abnormalities and confirmatory amniocentesis.

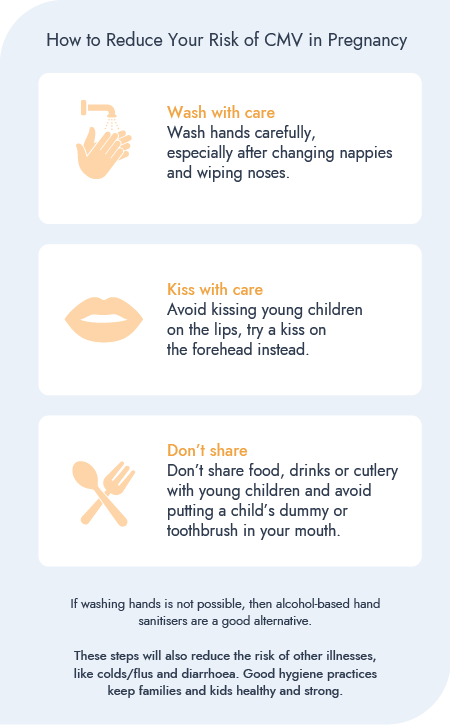

Primary Prevention: Hygiene Education

Despite its public health importance, community awareness of CMV is low, and up to 80% of pregnant women have never heard of CMV.8 Education on hygiene measures can reduce the risk of CMV acquisition during pregnancy9 and it is recommended that all pregnant people should receive this advice, regardless of their serological status.10,11,12 (Figure 2)

Information about these hygiene precautions should be provided as early as possible in pregnancy or pre-conception, due to the increased risk of fetal complications resulting from maternal CMV infection in the first trimester.

Numerous studies have shown that pregnant women want to receive CMV prevention information from maternity health professionals, and that this knowledge is empowering and motivating.8,14 The Cerebral Palsy Alliance has developed a range of information pamphlets and other resources in a variety of languages that are freely available for clinicians and consumers to download or order. This includes a two-minute educational video which has been shown to improve pregnant women’s knowledge and intention to practice prevention behaviours.15

Figure 2. Congenital CMV hygiene recommendation.13

Targeted Antenatal CMV Serology (CMV IgG) for Those at High Risk of Infection

The recently updated Australian Pregnancy Care Guidelines recommend CMV IgG at the first antenatal visit for all high-risk women (mothers of young children or those who work in childcare).10,11 CMV education can significantly reduce the risk of primary CMV infection in pregnancy from 7.6% to 1.6% among this high-risk group.16

Clinically Indicated CMV Testing (CMV IgG and IgM) for Those with Symptoms

Clinical features suggestive of CMV include flu-like illness, fever, and lymphadenopathy. Laboratory features that can accompany clinical CMV infection include atypical lymphocytosis, thrombocytopenia, elevated transaminases, and haemolytic anaemia.

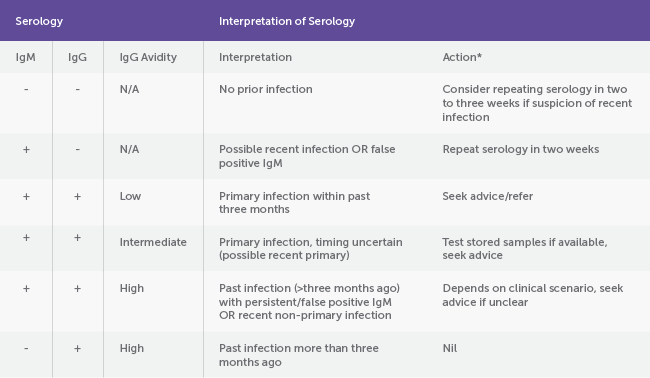

Pregnant women with the above symptoms should be tested for CMV IgG and IgM, and IgG avidity if both CMV IgG and IgM are positive.10,11 CMV IgG avidity is important for determining the timing of maternal infection and therefore, fetal risk.

A diagnosis of primary CMV is based on seroconversion (appearance of CMV IgG in a woman who was previously IgG negative), or the presence of CMV IgG and IgM antibodies, with low avidity IgG. Low avidity IgG indicates infection within the past three months. High CMV IgG avidity indicates infection more than three months prior. (See table 1)

Table 1. Interpreting CMV serology10

*Share hygiene advice with all pregnant women

Prevention of Fetal Infection After Maternal Primary Infection in Early Pregnancy

There is now evidence from randomised and observational studies that maternal treatment with high dose valaciclovir after first trimester primary infection reduces the risk of fetal infection by approximately 70%.17 The occurrence of all adverse events in pregnant women taking valaciclovir was 3%, including 2% experiencing acute renal failure, which resolved after discontinuation of the drug.17

If maternal primary CMV infection is suspected in the first trimester, urgent referral to a specialist perinatal infection service is advised for expert counselling, discussion of antiviral therapy, and multidisciplinary care.10 Patient resources, such as a pamphlet on CMV in pregnancy developed by Australian experts, can be accessed from the Cerebral Palsy Alliance CMV Resource Hub (see below).

Fetal infection can only be confirmed via amniocentesis (PCR for CMV DNA), typically performed at least eight weeks from the time of presumed infection, and usually after 18-20 weeks’ gestation. Further information on fetal/infant prognosis after confirmed infection can be obtained via ultrasound and/or fetal MRI.

Psychosocial Support

A suspected diagnosis of CMV infection during pregnancy can have severe and prolonged psychological impacts on parents, regardless of the pregnancy outcome.18 Qualitative research has highlighted the importance of timely, sensitive and accurate information from supportive health care professionals in minimising distress and confusion for patients.18 Support groups may also be a useful source of information and peer support for women and families affected by a diagnosis of CMV infection in pregnancy.

Key Roles of the Maternity Care Provider

- For women planning pregnancy or in early pregnancy:

- Provide routine information on hygiene-based CMV risk-reduction strategies.

- Arrange serological testing (CMV IgG) for those at increased risk of exposure.

- Recognising the clinical features of CMV infection in pregnant women and initiating appropriate investigations.

- Interpreting CMV serology or sonographic signs of congenital infection and referring to maternal-fetal medicine or perinatal infection diseases specialists as required.

- Supporting shared decision-making regarding testing and treatment.

- Providing psychosocial support to women with suspected CMV infection and referring to CMV resources and support agencies (see resources below).

CMV Resources

- Free RANZCOG and RACGP CPD-accredited Perinatal Infections eLearning Module (Congenital CMV and syphilis)

- RANZCOG Fellows: Access via the College’s Acquire platform

- For GPs: register with Praxhub for this free course

- For Midwives: Australian College of Midwives has an accredited online module (accessible to ACM members and non-members)

- Patient support options

- Cerebral Palsy Alliance CMV Resource Hub: Downloadable pamphlets, videos, flyers and posters, including patient information sheets in multiple languages and for First Nations women. You can also order free hard copies of the pamphlets and posters for your office.

- Patient Information on Cytomegalovirus (CMV) Infection During Pregnancy

- RANZCOG Statement: Prevention of congenital cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection

- Australian Pregnancy Care Guidelines: See the CMV guidance under the Communicable Diseases section

References

- Ssentongo P, Hehnly C, Birungi P, et al. Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infection Burden and Epidemiologic Risk Factors in Countries With Universal Screening: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2021 Aug 2;4(8):e2120736.

- Boppana SB, Ross SA, Fowler KB. Congenital cytomegalovirus infection: clinical outcome. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57 Suppl 4(Suppl 4):S178-S181.

- Murph JR, Bale JF Jr. The natural history of acquired cytomegalovirus infection among children in group day care. Am J Dis Child. 1988;142(8):843-846.

- Balegamire SJ, McClymont E, Croteau A, Det al. Prevalence, incidence, and risk factors associated with cytomegalovirus infection in healthcare and childcare worker: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst Rev. 2022 Jun 27;11(1):131. d

- Chatzakis C, Ville Y, Makrydimas G, Dinas K, Zavlanos A, Sotiriadis A. Timing of primary maternal cytomegalovirus infection and rates of vertical transmission and fetal consequences. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020 Dec;223(6):870-883.e11.

- Marzan MB, Tripathi T, Dumville L, Watson J, Holmes NE, Hui L. Modelling maternal cytomegalovirus seroprevalence in Australia using maternal country of birth: Implications for antenatal screening medRxiv 2025.08.21.25333872; doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2025.08.21.25333872

- Kenneson A, Cannon MJ. Review and meta-analysis of the epidemiology of congenital cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection. Reviews in Medical Virology. 2007;17(4):253-276.

- Lazzaro, A., et al. Knowledge of congenital cytomegalovirus (CMV) in pregnant women in Australia is low, and improved with education, Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2019; 59: 843–849.

- Rodríguez-Muñoz, M.F., Martín-Martín, C., Kovacheva, K. et al.Hygiene-based measures for the prevention of cytomegalovirus infection in pregnant women: a systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth24, 172 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-024-06367-5

- The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RANZCOG). Prevention of congenital cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection. RANZCOG, 2019. Available at https://ranzcog.edu.au/?s=CMV [Accessed 02.07.2025]

- Australian Living Evidence Collaboration [Internet]. [cited 2024 Sep 27]. LEAPP. Available from: https://livingevidence.org.au/living-guidelines/leapp/, [accessed 02.07.2025]

- Leruez-Ville M, Chatzakis C, Lilleri D, et al. Consensus recommendation for prenatal, neonatal and postnatal management of congenital cytomegalovirus infection from the European congenital infection initiative (ECCI). Lancet Reg Health Eur 2024;40:100892.

- Cerebral Palsy Alliance, CMV resource hub, https://cerebralpalsy.org.au/our-research/research-projects-priorities/cmv/cmv-resource-hub/#social

- Montague, A. et al, Experiences of pregnant women and healthcare professionals of participating in a digital antenatal CMV education intervention, Midwifery, Volume 106,2022, 103249, ISSN 0266-6138, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2022.103249

- Tripathi T, Watson J, Smithers-Sheedy H, et al. A 2-Min Cytomegalovirus (CMV) Awareness Video Improves Pregnant Women’s Knowledge and Planned Adherence to Hygiene Precautions. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2025 Mar 25. doi: 10.1111/ajo.70016.

- Revello MG, Tibaldi C, Masuelli G, Fet al; CCPE Study Group. Prevention of Primary Cytomegalovirus Infection in Pregnancy. EBioMedicine. 2015 Aug 6;2(9):1205-10.

- D’Antonio F, Marinceu D, Prasad S, Khalil A. Effectiveness and safety of prenatal valacyclovir for congenital cytomegalovirus infection: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2023 Apr;61(4):436-444.

- Tripathi T, Watson J, Skrzypek H, Stump H, Lewis S, Hui L. “The anxiety coming up to every scan-It destroyed me”: A qualitative study of the lived experience of cytomegalovirus infection during pregnancy. Prenat Diagn. 2024 May;44(5):623-634.

Leave a Reply