Whilst we all have a healthy concern regarding the potential for one of our patients to die as a consequence of performing gynaecological surgery onthem, the likelihood that we might meet such an unfortunate outcome is, thankfully, small.

However, it behoves us all to develop and put in place protocols and procedures that will minimise harm at surgery. We should also have strategies in place for identifying, in a timely manner, the development of any complications following such surgery.

The 2005 joint report from RANZCOG and United Medical Protection1 (UMP) indicated a number of important features that emanate from legal claims:

- More than 50 per cent of laparoscopy-related claims are from thin women (although undoubtedly obesity is a major risk factor for poor outcomes).

- Laparoscopy and hysterectomy procedures constitute the majority of claims.

- Death only constituted one per cent of claims (although this does not necessarily reflect the incidence of death from gynaecological surgery).

- Delay in diagnosing adverse outcomes constitutes a significant proportion of the claims.

History

Modern surgery is highly sophisticated, often utilising the full gamut of antibiotics, blood transfusion, advanced anaesthetic skills, intensive care facilities and advanced surgical skills. Modern surgery also tends to be more complicated and utilises more complex equipment than previously. In addition, we are prepared to operate on women with more complex health problems than in the past. This is a trend that is likely to continue. With this in mind, it is worthwhile briefly reviewing some historical data. In 1948, Weir2 reported that 40 out of 1771 hysterectomies ended in death (2.25 per cent). In 2001, Varol et al3 reported on a ten-year review of mortality and morbidity from hysterectomy in an Australian teaching hospital, indicating a mortality of 1.5/1000 (0.15 per cent).

However, as in obstetrics, mortality is the ‘tip of the iceberg’ of overall morbidity. It is a crude indicator of adverse outcome. Morbidity constitutes the majority of the clinical headaches (and medico-legal issues1) that we must deal with. As such, the development of strategies to minimise morbidity will also help to address the ultimate complication of mortality.

Managing risk

It is not my intention to focus on death rates from individual procedures but, rather, to pose the question: How do we deal with managing risk in the widely disparate clinical settings in which

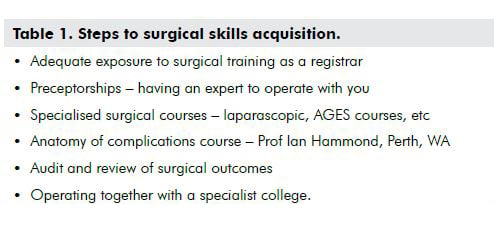

we practise – single practitioners, groups, associateships and partnerships, small provincial hospitals, large regional hospitals, university teaching departments and specialised subspecialist units?Ideally, risk management should start with our training as registrars, guided by our teachers. After that, we acquire specialised skills by continuing to learn in a myriad of ways (see Table 1). These steps are what most of us have followed throughout our career. A very good overview of the issues facing surgical training in our specialty is addressed in an article by Thierry Vancaillie in the AGES newsletter of July 20084, and merits reading by all who train, supervise or mentor for gynaecological surgery. It is clear there are a number of significant issues facing our Trainees and Fellows who seek to gain and maintain well-defined skills in gynaecological surgery.

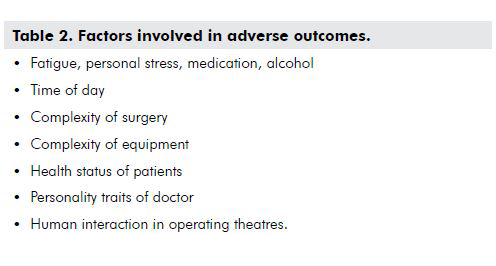

What are the issues that contribute to error? Recently, much has been written about the area of risk management in healthcare, but it would not be possible in this short article to cover the whole subject of risk management in gynaecology. Nonetheless it is something that all of us are going to need to incorporate into daily practice. Therefore, it is essential that, early in our careers, we learn to develop and update well-defined protocols and strategies in relation to our surgery.

The 2009 Productivity Commission report5 on health indicated that 124 out of 187 of the ‘core sentinel events’ recorded were surgical, with procedures being performed on the wrong body part, or retention of instruments or other material necessitating re-operation. In reality, these figures will only be part of the whole spectrum of adverse outcome that are not recorded, as there is no structured process to aid the recording of adverse outcomes in Australia.

Identifying risk

There have been frequent references in medical literature referring to the risk management strategies utilised by the aviation industry, suggesting that healthcare could look to the example of the aviation industry for direction in developing effective tools to monitor and assess adverse outcomes. The outcomes of such a process should help us to minimise the risk of harm occurring to our patients.

There are now surgical audits in most Australian States assessing all surgical deaths. The first audit started in Western Australia in 20016, based on the Scottish Audit of Surgical Mortality and Morbidity, and is covered by legislated qualified privilege. In fact, many of us might have had some involvement in such audits as i) the surgeon involved, ii) a first line assessor, or iii) a second line assessor. It is sometimes quite sobering to be involved. Importantly, such audits might in fact validate our practice. The audit process feeds information back to the surgeon involved. The first Western Australian audit indicated that 83 per cent of emergency and 68 per cent of elective surgery-related deaths had no deficiencies of care, which is news that involved surgeons would be relieved to hear. This study has resulted in 73 per cent of surgeons modifying their clinical practice.

The December edition of BJOG7 published its first ever article on a critical analysis of an adverse surgical outcome. The accompanying editorial comment merits reading and the link to the site (www.chfg.org) is worth visiting to look at the anaesthetic case.

Obviously, there is a evolution of risk management in medicine where autonomous practice was once the norm. Although most of us find the concept of extra documentation and audit tedious and time consuming, it is in our interests to become involved. Regulatory bodies are moving to incorporate such systems into routine medical care. Medical indemnity organisations now acknowledge that the introduction of risk management into clinical practice has reduced the medico-legal burden on the profession, and hence the cost of practice and our stress levels.

Where to from now?

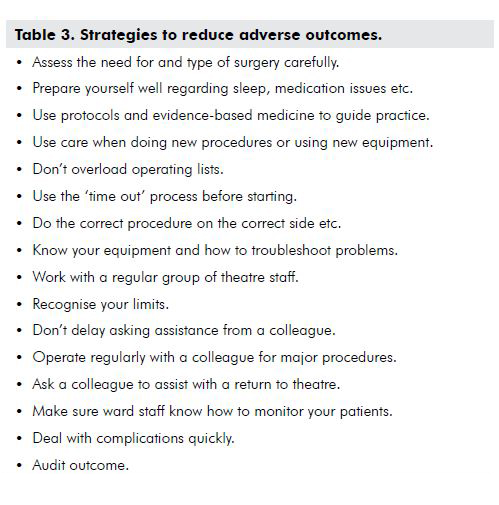

As the causes of adverse outcome of surgery are multifactorial, then the means by which we minimise harm are many. Table 3 indicates a (not exhaustive) list of suggestions.

All of us understand that surgery is inherently potentially linked to adverse outcomes, some of which are unavoidable in spite of best practice. However, all of us as practitioners can improve our practice, it is just a question of how much work we are prepared to put into our own form of risk management, within the professional structure that we practice in.

As an example, in our group of six O and Gs, we operate together regularly. In addition, we try to avoid public hospital on-call duties prior to an operating list the next morning. If there has been a busy private obstetric load leading up to the day of operating, we might arrange cover for the night before if the caseload is complicated. Some of our group have well-developed skills in particular procedures and will support performance of those procedures by others of us. Should we return to theatre with a post-operative bleed, large on-going postpartum haemorrhage (PPH), or other such event, then we will ask one of the group, who has no vested interest in the patient, to accompany us.

In summary, the issue of death from gynaecological surgery represents just part of the spectrum of adverse outcomes. Many well-developed processes have been produced to aid clinicians’ efforts to improve outcomes for our patients. However, implementation of these strategies requires that we be part of the process. Better that than have the formality of risk management imposed on us in a way we are not able to influence. It is important we demonstrate to the public that as gynaecologists, we are seriously addressing the welfare of our patients.

References

- Gynaecology, a claims review. A joint report from the Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists and United Medical Protection Limited.

- Weir W. A statistical report of 1771 cases of hysterectomy. Am J Obst & Gynec. December 1948; 56:1151-1155.

- Varol N, Healey M, Tang P, Sheehan P, Maher P, Hill D. Ten-year review of hysterectomy morbidity and mortality: can we change direction? ANZJOG; 41 (3): 295-302.

- Vancaillie T. Scope; Vol 37 July 2008: 10-14.

- Report on Government Services 2009 – Steering Committee for the Review of Government Service Provision Report. 30/1/09. Page E33, Table 10.16 (www.pc.gov.au/gsp/reports/rogs/2009 – expired link; search online at www.pc.gov.au) .

- Semmens J, Aitken R, Sanfilippo F, Mukhtar S, Haynes N and Mountain J. The Western Australian Audit of Surgical Mortality: advancing surgical accountability. MJA 2005; 183 (10): 504-508.

- Schonman R, De Cicco C, Corona R, Soriano D, Koninckx P. Accident analysis: factors contributing to a ureteric injury during deep endometriosis surgery. BJOG 2008; 115 (13): 1605-10.

Leave a Reply