Down syndrome (DS) was first described as a constellation of physical symptoms over a century ago and its genetic basis as Trisomy 21 (T21) described in 1959. In 2009, modern medicine and all its sophistication allows for advanced prenatal diagnosis and comprehensive management options for children born with this condition.

Nevertheless, the impact on families remains significant. In many instances, the diagnosis is known prior to delivery, allowing for education

and support of prospective parents. However, this is not always the case. The most challenging families to support in the newborn period are those in whom the birth of a child with Down syndrome is completely unexpected.

The purpose of this article is to arm obstetricians, general practitioners and other antenatal healthcare workers with a broad understanding of Down syndrome, and what parents might seek to discuss to better understand the path ahead in terms of raising and caring for their children. Current issues regarding screening and diagnosis are addressed elsewhere in this edition of O&G.

The antenatal period

Once a prenatal diagnosis is made, there are naturally a great deal of questions posed to medical practitioners regarding the pregnancy itself and expectations along the way. Paediatricians can be usefully engaged in this process if needed. For the sake of this article, we shall presume that the parents wish to proceed with the pregnancy. Of course, they may decide to pursue other options such as termination or adoption. The typical discussion points would include:

-

The diagnosis itself

Usually made by the first trimester combined test (PAPP-A, hCG and nuchal translucency).

-

Why has it occurred?

There is more than one genetic event that can lead to Trisomy 21. The great majority are nonfamilial, involving an extra copy of chromosome 21. A small proportion are inherited chromosome 21 abnormalities. Genetic consultations with families can be very helpful in both explaining the diagnostic genetics and offering counselling support.

-

Are there additional tests that need to be done during the pregnancy?

Yes, there may be.

-

Fetal cardiac assessment

Approximately 50 per cent of DS children will have congenital cardiac defects, the most common being atrioventricular septal defect (AVSD) or ventricular septal defect (VSD). These may have clinical relevance in the newborn period and so fetal cardiac echo is recommended, so that delivery can occur in an appropriate high-risk setting if needed.

-

Gastrointestinal imaging (GI)

Five per cent of DS children will have significant GI

anomalies, the most common being duodenal atresia or stenosis. Ultrasonography will assist with the diagnosis. Delivery should occur in a tertiary setting.

-

-

Prognostications

This is very difficult to address accurately, as there is great variation. Children with DS are at an increased risk of a number of medical conditions, as described below. In an ideal clinical setting, parents could be fully informed of the potential future medical challenges. However, in the first instance, this may be overwhelming and individual judgment needs to be made in terms of how detailed a discussion should take place and the timing of that discussion.

Genetic counselling

Clinical geneticist involvement can be extremely helpful to enable more indepth discussion of the diagnostic genetics and associated phenotypic variability; future pregnancy risks for primary and distant relatives; and options for prenatal testing with any future pregnancy.

Associated medical conditions

In addition to the cardiac and GI abnormalities discussed above, a number of medical problems can add to the challenge of raising a child with Down syndrome.

Intellectual impairment

Cognitive impairment is common and of varying severity. Developmental delays across all parameters are generally detected early. Early intervention services are integral to maximising cognitive potential and are discussed later in this article.

Disproportionate growth

Short stature and overweight/obesity are common. The aetiology of short stature is not clear in the literature; varying roles for GH and IGF-1 have been postulated but not clarified. Slow metabolic rate could explain the weight gain, although modern lifestyle factors are just as relevant for DS children as their unaffected peers.

Hearing and vision abnormalities

Hearing impairment can affect many DS children and can be either conductive, sensorineural or mixed. Recurrent otitis media can exacerbate underlying hearing deficits. Visual problems affect the majority and are usually refractive errors or squints.

Endocrine abnormalities

Thyroid dysfunction occurs with varying frequency and can be hypo- or hyperfunction. It is not unusual for neonates to have TSH and thyroid hormone levels outside the normal range, without underlying pathology. Insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus is more common in DS children.

Haematological conditions

- Normal variations – polycythaemia, thrombocytosis, leukopaenia, macrocytosis.

- Transient Myeloproliferative Disorder – usually asymptomatic and self-resolving in the first few months of life. Complications can, however, be life-threatening in a small number of cases.

- Acute myetoid leukaemia (AML) and acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL) – both much more common in DS children than unaffected peers. Chemotherapy toxicity and therefore morbidity and mortality, are also higher in DS patients.

Sleep disorders

Obstructive sleep apnoea is very common, regardless of weight. Both anatomical and neuromuscular factors are implicated – hypotonia, large tongue, midface hypoplasia and a high-arched palate contribute to varying degrees.

Other conditions

- Atlantoaxial instability (AAI) – excess movement of C1 on C2, which, in a very small number, may cause spinal cord compression. The majority of children are asymptomatic and screening for AAI is controversial in these asymptomatic cases.

- Coeliac disease – strong association with DS, with varying reports of five to 15 per cent incidence.

- Hirschsprung disease – more common, although less than one per cent risk.

- Impaired reproduction – males are almost universally infertile due to defective spermatogenesis. Females are fertile – the risk of a DS offspring is dependent on the underlying maternal genetics and pre-conception genetic counselling is highly recommended in these cases.

- Skin disorders – very common, and include folliculitis, seborrhoeic dermatitis and hyperkeratosis.

- Behavioural problems – attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) are the most common. Psychiatric disorders are also more prevalent in those with DS.

The road ahead – medical surveillance

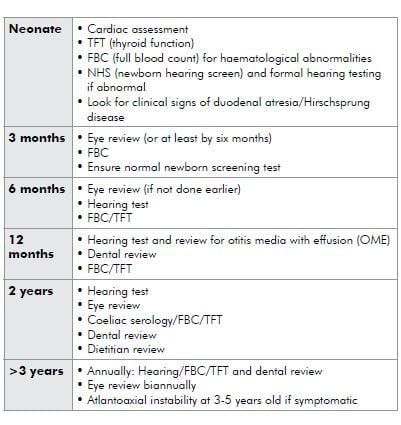

The practicalities of managing children with DS primarily revolve around ongoing medical surveillance for the above associated conditions. As children are affected by different conditions at different ages, surveillance can be tailored to the age group. Different peak paediatric bodies have published surveillance regimes of varying intensity and complexity. I use the following approach:

The road ahead – early intervention services

Early intervention for any child with a disability or developmental difficulties is critical in maximising their cognitive and social potential. Early intervention should be married with medical surveillance and is often as important, if not more so.

Early intervention obviously needs to be tailored to the individual’s needs, but it is not uncommon for DS children to require involvement from speech pathologists, occupational therapists, physiotherapists and dietitians. There is no question that outcome is directly proportional to the amount of early intervention received. Unfortunately, access is not always easily achievable, both from a geographic and financial perspective. Many services need to be accessed via private allied health practitioners. State Down syndrome associations can assist with directing families to both publicly-funded community and private services.

Additional family support and information

There are many different support agencies, networks and resources available for children, parents and families who have a relative with Down sydnrome. Both State and Federal governments and organisations have programs and funding arrangements in place to assist. It can take time and patience to get one’s head around what is available in a particular geographic area for a particular special needs child, regardless of the overriding diagnosis.

There are Down Syndrome Associations in each State and they are an excellent place to start for families with a new diagnosis, or families looking to access more information. A multitude of educational and support materials are available on a state-by-state basis. I recommend families explore state associations in addition to their own home state, as each tends to present a variety of support materials and programs.

The genetics of Down syndrome is important for parents to have at least a basic understanding of, as many issues arise surrounding current and future pregnancies. The Centre for Genetics Education (www.genetics.edu.au) provides excellent fact sheets for parents explaining the genetic basis of Down syndrome. This can supplement consultations with a clinical geneticist and/or genetic counsellor.

Education is obviously an enormous aspect of any child’s development. Needless to say, DS children’s educational needs vary with cognitive level and require appropriate thought and consideration. In New South Wales, Australia, the Department of Education and Training is engaged in the schooling placement process and offers a number of schooling options. This should be paralleled in other States:

- Mainstream classes

- Support classes in mainstream schools

- Special schools (via a regional placement panel)

- Learning Assistance Programs – supporting students with learning difficulties in mainstream classes, regardless of the cause.

Caring for any child with a disability, or indeed any child with a significant medical condition, can be testing even for the most dedicated carer. Individuals can feel overwhelmed, marriages

can strain and siblings can struggle with the necessary time and attention that special needs children require. Managing families as a whole is an important aspect to the overall management of

a child with DS. Respite can be helpful in this process and can be accessed in various community settings. Respite funding is available via Commonwealth Carer Respite Centres (phone 1800 059 059 in Australia).

Summary

Down syndrome is the most common chromosomal abnormality amongst newborns and indeed the most common chromosomal cause of intellectual impairment. Not only do these children face substantial medical and developmental hurdles, their families naturally take on a considerable burden of care beyond normal parenting responsibilities. The initial diagnostic period can be emotionally challenging and confronting, and appropriate supports are critical in the early phases in particular. Those supports then naturally evolve into the provision of ongoing medical surveillance and early intervention services so that children can reach their social and cognitive potential. Healthcare professionals and support organisations can complement each other in guiding parents through the differing care phases of these children.

Leave a Reply