Urogynaecology is the subspecialty in obstetrics and gynaecology that has, in our view, been the most controversial in Australia. Why is it so? Some may think that urogynaecology is nothing but operative pelvic surgery that any Fellow should be able to do.

Others might think the subspecialty is more about creating a niche market for a select few. Others probably wonder what a subspecialty Fellow does for three years during training if the previous two perceptions are true.

A broad review of urogynaecology-related scientific work reveals significant developments and new directions evolving over the past decade. urogynaecologists and basic scientists have carried out important research in many areas that drives the subspecialty towards new and useful knowledge. There has been increased focus on cell biology, tissue physiology and biochemistry of the lower urinary tract, in an effort to understand the pathophysiology of the overactive bladder and lower gastrointestinal (GI) tract, and management of associated conditions.1

Urethral function has received more interest than ever and pathophysiological considerations have shifted from the long-held paradigms regarding bladder neck mobility associated with vaginal prolapse in the genesis of stress incontinence.2 Imaging of pelvic organs made strides in terms of ‘what to image’, qualitative and quantitative standards for imaging and, more importantly, validity and the predictive value of imaging studies in comparison to existing gold standards of treatment.3,4 Also, 3D ultrasound scan technology has enabled us to assess mesh behaviour, erosions and failures to some degree, and the field is continuing to evolve. Paradigm changes also occurred in the treatment of interstitial cystitis and the new approach now places emphasis on a more comprehensive approach to bladder pain syndrome (BPS). The concept of anatomical support and creation of fascial planes influenced the development of a variety of surgical procedures and prosthetic (mesh) kits. The advent of mesh kits also resulted in numerous studies and attracted criticisms towards surgeons for lack of rigour in design and analysis.

In our opinion, the Pacific region has also made significant contributions over the decade, with some leading research and inventions related to the field. Professor Zacharin’s study of pelvic floor anatomy, Professor Petros’ integral theory, the sub-urethral sling procedure and the infracoccygeal sacropexy, were just a few of these contributions. Other major events included the inventions of Perigee and Prosima. Professor Dietz has changed our thinking about visualising pelvic floor structures with ultrasound and his concepts of levator avulsion.5 Subspecialty training programs around the world observed these significant developments within the field and incorporated changes to prepare the future workforce.

RANZCOG in Australia revised its certification training program in 2009 and introduced a more detailed curriculum that placed emphasis on program content and rigour. Current subspecialty training programs typically involve two years of extensive training in an accredited unit and an elective year designed by the trainee based on clinical focus and skill requirements of the individual. Entry and successful participation requires a trainee to have long-term interests in the subspecialty and willingness to teach and actively engage in research. Also, participation in an accredited training program often involves relocations and financial decisions due to the nature of training requirements that do not necessarily place the emphasis on competitive incomes for a Fellow. The training units also face increasing scrutiny in terms of quality of the programs provided. RANZCOG requires not just the number of procedures done, but also research output and a 66 per cent pure participation subsequent to certification as a subspecialist.

The fast-paced developments do attract a lot of interest among general specialists who wish to develop special interest in urogynaecology and provide related services as a part of their practice. While such interest is generally well-received, it is emphasised that general specialists be provided with appropriate training that will cover all aspects of treating urogynaecological conditions, such as assessment, investigations, appropriate treatment choices and follow-up of complications; not just learning to perform procedures. The urogynaecology subspecialty, in this regard, faces challenges in the design and development of ‘appropriate’ training content for specialists who express special interest. As one of the centres that offer ‘hands-on training’ for specialists in urogynaecological procedures, for us the basic question remains the same. Should we or can we be selective in training surgeons who are expected to do high volume pelvic reconstructive surgeries as specialists and how do we even define what a high volume is? Once training is completed, how effectively are we monitoring the surgeons for performance and complications? Should we even monitor? To a great degree, industry does seem to play a major role in the development of different kits, choice of kits and a push for training more general specialists in pelvic reconstructive surgery.

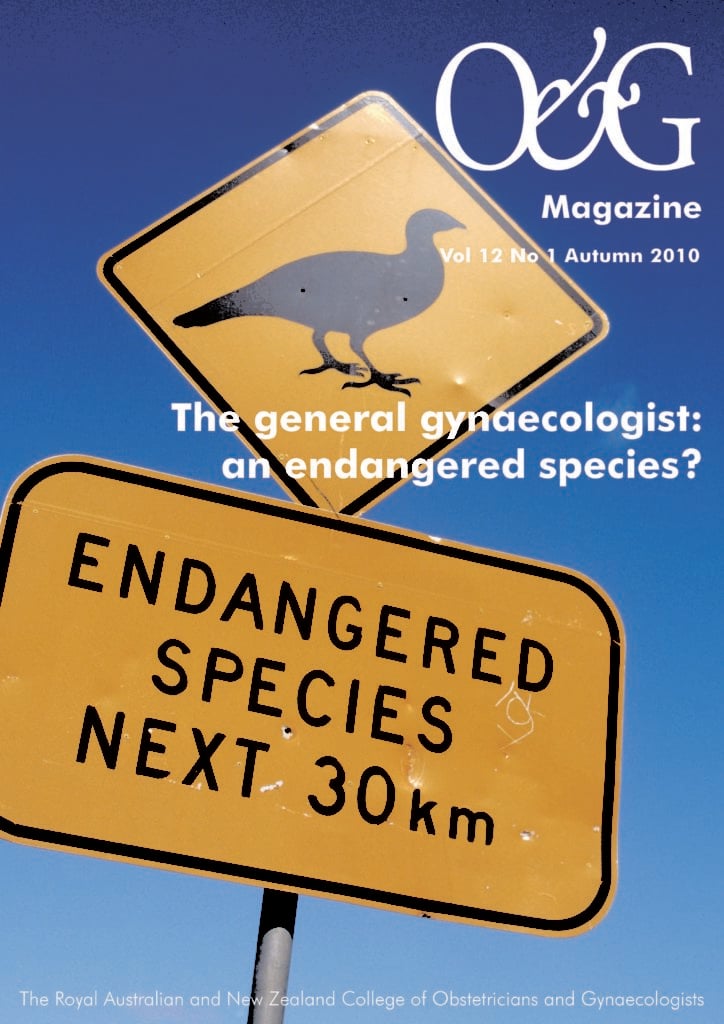

While such questions remain, it is also well-acknowledged that general gynaecologists should be offered training programs that will help them gain a broad understanding of pelvic floor dysfunction encountered in office practice, associated risk factors, appropriate assessment techniques, preventive measures and handling of simple, proven procedures. The subspecialty must strive to design and develop training programs that will impart such skills to specialists and evince interest in urogynaecology, while continuing to find and validate new knowledge with the robust application of research principles and framework. One of the purposes of having a subspecialty is to acquire knowledge, specialised expertise and related training in a specific field that will help one provide the best possible care to a patient in need and that approach should provide the context to define the scope of the specialist and the subspecialist. The caveat ‘what can the general gynaecologist do’ then ceases to exist.

References

- Andersson KE, Arner A. urinary bladder contraction and relaxation: physiology and pathophysiology. Physiol Rev. 2004: 84: 935-986.

- Kamo I, et al. Functional analysis of active urethral closure mechanisms under sneeze induced stress condition in a rat model of birth trauma. J urol. 2006. 176(6 Pt 1): p 2711-5.

- Maglinte DD, Kelvin FM, Fitzgerald K, et al. Association of compartment defects in pelvic floor dysfunction. Am J Roentgenol. 172:439444, 1999.

- Dietz HP, Lekskulchai O. ultrasound assessment of pelvic organ prolapse: the relationship between prolapse severity and symptoms. ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2007 Jun; 29(6):688-5.

- Dietz HP, Lanzarone V. Levator trauma after vaginal delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2005 Oct; 106(4):707-12.

Leave a Reply