Dealing with pain requires an open mind – there is more to the pelvis than the uterus and ovaries.

Despite the fact that management of pain is the first and foremost on Hippocrates’s list of duties for physicians, we’re not doing that well, I would say. A few basic points are worth discussing: first, the concept that pain is a normal experience. In parallel with ‘normal’ menstrual bleeding, there is what can be called ‘normal pelvic pain’. Both concepts are subjective: what’s normal for one individual is not necessarily normal for another. The main reason to emphasise this is that many healthcare providers will have a tendency to project their ‘norms’ on to their patients and get on to the wrong foot from the start, not willing to consider the complaints at hand as ‘abnormal’, or simply insisting on a set of standards, which don’t really exist. For many colleagues, pelvic pain is mostly an expression of endometriosis and the variety of symptoms among patients is simply due to the variety of location and severity and so on. For many of us, endometriosis is pelvic pain, we’re trained to remove it and we expect the patient to come back after surgery stating she has no more pain. I must admit, I was among this group of physicians for a long period of time. I was wrong. Endometriosis does not equal pain; neither does cystitis, haemorrhoids, fibroids and so on. Endometriosis is a stimulus that enters the nervous system and that may eventually contribute to a pain experience or not. Finally, and not surprisingly, gynaecologists have a tendency to focus on the uterus and ovaries, sometimes including the bladder, but rarely any other anatomic structure of the pelvis. When it comes to pain, however, there is certainly more to the pelvis than the uterus.

Current concepts in pain physiology

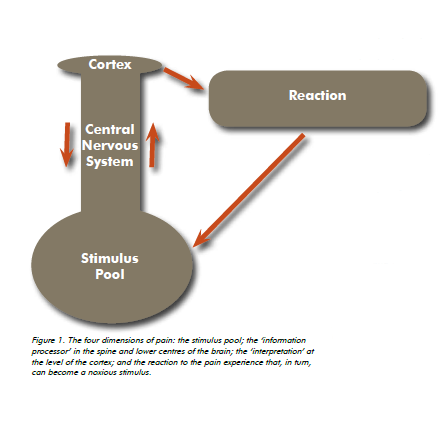

Perceiving pain is the result of a complex sequence of events. All events, external (for example, walking) as well as internal (for example, the filling of the bladder), generate a stimulus. There are thousands of stimuli generated every minute of the day. All stimuli enter our personal information processor, involving the spine and the lower centres of the brain. A multitude of modifiers influence the impact of each stimulus, mainly the co-existence of other events and the influence of the higher centres of the brain. The dominant influence is down regulation: stimuli are minimised and do not result in the perception of pain.

Differences among individuals are the result of differences in genome as well as variability in environmental factors, such as family, religion, country, presence or absence of war and so on. Our genome forms the roots, which grow a ‘neuro-biologic’ tree. Depending on the environment in which the tree grows, it will bear particular somatic fruit: certain individuals are prone to headaches; others tend to develop a sore back and so on.

Our information processor has a few bad habits: convergence and sensitisation. Convergence occurs when stimuli within one dermatome merge and become indiscriminate to source. The pudendal nerve, for instance, emerges from S2, S3 and S4. The S2 dermatome also involves the dorsal aspect of the leg down

to the foot. Patients with pathology involving the pudendal nerve can therefore present with pain along the plantar aspect of the foot (no, they’re not crazy). Sensitisation means that occurrence of one stimulus augments the strength of another. Menstruation, for instance, is a potent peripheral sensitiser. Any noxious stimulus will be perceived as ‘worse’ during menses, even if that stimulus is not within the pelvis. Oestrogen is a potent central sensitiser. Professor Karen Berkeley has spent decades of research demonstrating that oestrogen enhances the strength of noxious stimuli through direct influence on the brain. Her landmark publication The Pains of Endometriosis is a real eye opener.

Last, but not least, there is ‘the fourth dimension’: any pain experience will generate a musculo-skeletal response, a variation on the flight reflex: if it hurts, run away. Stimuli originating within the pelvis and resulting in pain will cause the pelvic floor muscles to contract. When a noxious stimulus persists, it is possible for the pelvic floor muscles to contract abnormally and thus become a further noxious stimulus.

As a result of the above concepts in pain physiology, we should understand there is no such thing as ‘endometriosis pain’, let’s just call it pelvic pain, maybe the presence of endometriosis is a contributing factor. We should accept that the intensity of pain is variable from one day to another, without necessarily any of the stimuli being ‘worse’. The offending stimulus may be ‘better’ and still the perception of pain is more intense. We should understand that any and every bodily system participates in the generation of the pelvic pain experience and we should therefore be willing to revisit a diagnosis we thought was watertight.

Once we understand these concepts, we’re ready to examine the patient complaining of pelvic pain.

Physical examination of the patient with pelvic pain

With growing experience in dealing with patients complaining of pelvic pain, I have come to the conclusion that the uterus and ovaries are not the main stimulus generators resulting in pelvic pain. It is, I believe, the musculoskeletal system that generates the largest pool of stimuli, eventually contributing to the perception of pain. Unfortunately, most of us have not been exposed to examination of the musculoskeletal system during our training. It takes some effort to include a minimum clinical examination and discern features that could potentially be a major contributor to the pain experience such as scoliosis, sacro-iliac joint tenderness and so on. At the least, a referral to a rheumatologist, sport physician, osteopath or physiatrist would be in order. Where we do have a major role to fulfil is in the identification of pelvic floor muscle dysfunction and pudendal nerve pathology. There is no other specialist to refer the patient to. We need to take on that responsibility. The levator and obturator internus muscles should be palpated during rest and during isometric contraction. If pain is generated with gentle digital pressure during isometric contraction, then the patient is said to have ‘myalgia’, which is essentially stating the muscle hurts. The pudendal nerve runs within the Alcock canal, which stretches from the ischial spine to the descending ramus of the pubic bone. The Alcock canal is formed by a duplication of the obturator internus fascia below the linea alba, site of insertion of the levator ani. This anatomic relationship immediately highlights the intimate relationship between the pelvic floor muscles and the pudendal nerve.

Pressure below the ischial spine, which corresponds to the entry into Alcock canal, sometimes reproduces the pain that the patient is complaining of (either immediately or with some delay). This is called ’Tinel’s sign’, after the French neurologist who described how pressure at the entry of the carpal tunnel reproduces pain in patients with carpal tunnel syndrome. Some will say that the presence of a ‘Tinel’s sign’ at the entry of Alcock canal is an indicator of pudendal nerve entrapment. That correlation has not been subjected to scrutiny yet.

The objective of the examiner is to evaluate all major body systems (skin, nerves, vessels, muscle, bone, viscera) and to form a composite image of the stimulus pool for each particular patient, which I call a ‘vario-gram’. This sort of exercise will avoid focusing on one and only one stimulus as the culprit for the pain syndrome. As for the term ‘vario-gram’, it emphasises the notion of variability of symptoms. This variability means symptoms and findings can change at any time. It also means treatment, such as resection of endometriosis, will not necessarily result in the elimination of all symptoms.

Treatment of pelvic pain

Stating that treatment of pelvic pain should be a multidisciplinary effort must sound like a broken record by now. I prefer to say the gynaecologist should keep the driver’s seat, but he/she needs to create a multidisciplinary mindset in his/her approach to treating patients. However, we are not trained to administer treatment modalities such as those mastered by the osteopath, physiotherapist, acupuncturist and psychologist. Complex pharmacological regimens also require input from other specialists and we should refer patients found to have auto-immune or other conditions with a pain component to the appropriate specialist. A multidisciplinary network does need to be in place when dealing with patients presenting with abnormal pelvic and perineal pain.

Laparoscopy and resection of endometriosis or other intervention, does remain an important part of our armamentarium in the fight against abnormal pain. Removing the noxious stimuli, endometriosis and others alike, results in marked improvement for the patient in the majority of cases. By no means should my position be interpreted as the demise of laparoscopy for the management of endometriosis – certainly not. On the other hand, a laparoscopy every other year is clearly not the answer to chronic pelvic pain.

In an ideal world, the gynaecologist is able to discern the various aspects that enter into the equation early on in the process and is therefore in a position to formulate an appropriate treatment plan. As the equation is complex, the task becomes far more achievable from the moment collaboration occurs between two or three individuals, such as a gynaecologist, physiotherapist and osteopath. The skill sets of these health-care providers are truly complementary and therefore the chance of a better understanding of the patient’s status greatly increases. It is difficult to identify and differentiate between signs such as myalgia, muscle over-contraction, wind-up, trigger point, Tinel’s sign, tissue pliability, cervical motion tenderness, hyper-algesia and so on. A built-in second opinion is a valuable tool in the management of patients with abnormal pelvic pain, especially if the condition has been long-standing and refractory to treatment.

Introducing medications such as Amitriptyline and Neurontin, identifying and treating painful scars, infiltrations of the pelvic floor muscles with botulinum toxin, performing pudendal nerve blocks and so on, are modalities that contribute to the treatment of patients with abnormal pelvic and perineal pain. These modalities can be mastered by gynaecologists, if an interest in treating abnormal pelvic and perineal pain exists. However, it should also be emphasised, for instance, that injecting botulinum toxin is not a treatment per se. It is the physiotherapeutic re-education of the pelvic floor muscles in this instance, which is important. Botulinum toxin is a facilitator of that. The same applies to a number of other treatment modalities: they all need to form part of a treatment program and are rarely self-sufficient.

References

Berkeley K, Rapkin A, Papka R The Pains of Endometriosis Science 308, 1587-9, 2005.

Howard F. Chronic Pelvic Pain Obstet Gynecol, 101, 594-611, 2003.

Gillett WR, Jones D. Chronic pelvic pain in women Expert Rev Obstet Gynecol, 4, 149-163, 2009.

Leave a Reply