One of the most complex and challenging complaints facing a gynaecology consultant is dyspareunia. Painful intercourse is a multifactorial complaint and we have to approach the problem in a logical and systematic manner in order to arrive at the aetiology of the pain.

Dyspareunia is a difficult subject for women to discuss with a healthcare provider and often goes unreported1; however, the incidence is reported to be as high as 20 per cent.2,3 There is certainly nothing new about this complaint, but there are some new approaches being developed to help clinicians with the diagnosis and treatment of dyspareunia. It is tempting to attribute sexual pain to emotional and psychological issues and we cannot discount their impact, but the majority of cases have a physical basis. A concise and effective way4 to approach your patient is to divide the aetiologies into local causes (vulvar dermatoses, vaginitis, pelvic floor muscle dysfunction, obstetric trauma and so forth) and referred pain (disease in pelvic viscera, prolapse, neuropathy). Many women will have more than one cause of the pain and almost all will have psychosocial repercussions that impact on their relationships.

As with all pain disorders, it is necessary to obtain a detailed history of the pain, including onset, timing, quality, what makes it better or worse, associated symptoms and referred pain. History alone will help identify a cause in many cases. Women with vulval disease report itching, pain is superficial and worse overnight, and symptoms may be relieved by steroids. Women with a neuromuscular component to their pain will complain of stabbing, an electric or burning sensation, the pain will be gradual and chronic, often worse in evening and relieved by rest. When there is a deep dyspareunia, pain is localised to the pelvic viscera due to endometriosis, pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) or ovarian or uterine pathology.5

Associated symptoms, such as vaginal discharge, urinary frequency or incontinence and bowel dysfunction or faecal incontinence, are important to elicit. A lack of arousal accounts for pain due to a lack of lubrication so a sexual and relationship history is required.6 Medical problems such as asthma, psoriasis and diabetes can contribute as well as obstetric/gynaecologic history of trauma, lactation or menopause. A medication history is important as many women have tried multiple topical medications to attempt to relieve the pain. Some of these are common causes of contact dermatitis and include: benzocaine, diphenhydramine, neomycin, steroids and imidazoles as well as additives in creams such as ethylenediamine, parabens, chlorcresol and benzyl alcohol.6

Examining your patient can be challenging and may have to occur in stages. An abdominal exam can identify point tenderness, which can aid in the diagnosis of pelvic pathology. A visual exam can often point you in the right direction immediately. Look for skin fissures, discolouration, ulcers, changes in the anatomy and architecture of the vulva, erosions, erythema, excoriations and oedema. A sensory examination with a swab at the introitus can elicit neuropathic pain, which may persist after removal of the swab. A speculum exam is often impossible with dyspareunia, but a gentle digital exam may be acceptable to the woman. This can help localise the pain and the levator ani muscle can be assessed for tone, strength and tenderness. A speculum exam may be attempted, but in some cases may only be achieved after treatment with pelvic floor trainers.

The initial diagnostic studies are simple. Swabs should be taken of any vulvar ulcer, a high vaginal swab is necessary to rule out vaginitis and skin biopsy is indicated by the findings of a lesion on vulvar examination. Rarely is a pelvic ultrasound of any benefit in diagnosis unless there was a specific finding on abdominal or bimanual exam such as adnexal or uterine mass. Diagnostic laparoscopy may be used to exclude endometriosis when a patient complains of a deep dyspareunia.

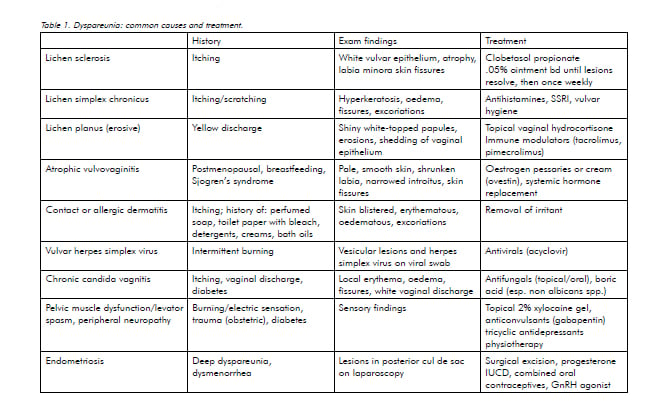

Treatments for dyspareunia are as varied as the diagnoses. Local causes such as vulvar dermatoses and infections require localised or topical treatment. Pelvic floor dysfunction requires intense physiotherapy to retrain the pelvic floor muscles.7,8 This includes self-exploration and the use of graduated dilators with relaxation techniques, including the partner only when the woman is comfortable. Advances in this area include biofeedback and the use of botulinum toxin injected into the levator ani muscles to decrease muscle bulk and activity in order to allow easier use of vaginal dilators.9,10,11 Referred pain, such as neuropathic pain and deep pelvic pain that cannot be treated with hormonal treatment or surgery, can often be treated with anticonvulsants and antidepressants.12 Table 1 provides many of the causes of dyspareunia and includes diagnostic clues from the history and examination as well as recommended treatments.13,14

Dyspareunia is a non-specific symptom for a multitude of complex gynaecological problems. It often creates frustration in both the patient and the clinician, and treatment in many cases is not simply medical or surgical, but may require a long process of physical therapy. However, when time is taken to really tease out the underlying cause of the dyspareunia and treat it accordingly, it can be satisfying for the clinician and life-changing for your patient and her partner.

References

- Latthe P, Latthe M, Say L, Gulrnezoglu M, Khan KS. WHO systematic review of prevalence of chronic pelvic pain: a neglected reproductive health morbidity. BMC Public Health 2006; 6: 177-83.

- Danielsson I, Sjoberg I, Stenlund H, Wikman M. Prevalence and incidence of prolonged and severe dyspareunia in women: results from a population study. Scand J Public Health 2003; 31: 113.

- Jamieson DT, Steege JF. The prevalence of dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, pelvic pain and irritable bowel syndrome in primary care practices. Obstet Gynecol 1996; 87: 55.

- Bradford J. Vulval pain and entry dyspareunia: a new approach to old problems. Presented at: Australia New Zealand Vulvovaginal Society International Conference; 2010 November 12-14; Queensland, Australia.

- Latthe P, Mignini L, Gray R et al. Factors predisposing women to chronic pelvic pain: systematic review. BMJ 2006; 332: 749.

- Howard JR. Helping People with Sexual Problems. Melbourne: IP Communications; 2010. p. 171-186.

- McGuire H, Hawton K. Interventions for vaginismus. Cochrane database Syst Rev 2003.

- Crowley T, Goldmeir D, Hiller J. Diagnosing and managing vaginismus. BMJ 2009; 338: b2284.

- Vancaille T. Botulinum Toxin: what role in entry dyspareunia. Presented at: Australia New Zealand Vulvovaginal Society International Conference; 2010 November 12-14; Queensland, Australia.

- Shafik A, ElSibai O. Vaginismus: results of treatment with botulinum toxin. J Obstet Gynaecol 2000; 20: 300.

- Ghazizadeh S, Nikzad M. Botulinum toxin in the treatment of refractory vaginismus. Obstet Gynecol 2004; 104: 922.

- Steege JF, Zolnoun DA. Evaluation and treatment of dyspareunia. Obstet Gynecol 2009; 113: 1124.

- Ferrero S, Ragni N, Remorgids V. Deep dyspareunia: causes, treatments and results. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2008; 20: 394.

- Harris N. Use of neuropathic pain relievers. Presented at: Australia New Zealand Vulvovaginal Society International Conference; 2010 November 12-14; Queensland, Australia.

very well maintained blog . and it is useful for people suffering Dyspareunia