Once adequately identified, obstetric anal sphincter injuries – a surprisingly frequent complication of vaginal birth – generally respond well to treatment.

Third and fourth degree perineal injuries, these days commonly abbreviated as OASIS (obstetric anal sphincter injuries), are a particularly unpleasant complication of vaginal birth, due to the risk of long-term morbidity such as anal incontinence (up to 25 per cent), perineal discomfort and dyspareunia (up to ten per cent) and, rarely, recto-vaginal fistula.1,2 Third degree perineal injury is partial or complete disruption of the muscles that make up the anal sphincter complex, the external anal sphincter (EAS) and the internal anal sphincter (IAS), and either or both of these may be involved. These tears are commonly subclassified as:

- 3a – no more than half of the EAS is disrupted

- 3b – more than half of the EAS is disrupted

- 3c – both the EAS and the IAS are completely disrupted

Fourth degree injury is characterised by sphincter disruption and tearing of the anal epithelium.

Such injuries are now surprisingly common, particularly in first births. Benchmarking data from the Australian Council on Healthcare Standards (ACHS) reports a third-degree tear rate of 4.3 per cent in young women having their first baby (the ‘selected primigravida’), though this reported rate is higher in public hospitals and lower in private hospitals, a difference that has been described elsewhere.3 Fortunately, the rate of fourth degree tear in primigravid deliveries is reported as considerably less than 0.5 per cent. The risk of OASIS is lower in multiparous women, contributing to an overall reported rate of about one per cent for all births in Australia. It is important to note that studies employing endoanal ultrasound in the postnatal period have suggested that as many as a third of women will sustain an unrecognised anal sphincter injury after their first vaginal birth.4,5

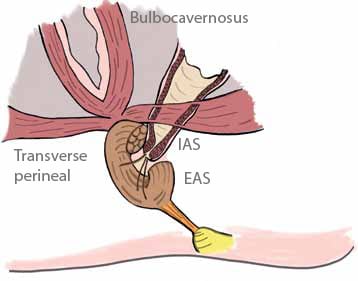

Anatomy of the perineum

The anatomy of the perineum is shown in Figure 1. Deep to the perineal skin is the perineal body, located between the fourchette and anus. It is composed primarily of the intersection of the transverse perineal muscles and the bulbocavernosus, with some deeper fibres from the puborectalis muscle and the IAS. The anal sphincter complex lies inferior to the perineal body. The EAS is composed of striated skeletal muscle, whereas the IAS is formed by smooth muscle, continuous with the muscle of the colonic wall. The IAS is largely responsible for the baseline tone of the sphincter and thus passive anal continence.

Risk factors

A number of risk factors are now well recognised, although their value in both prediction of injury, and indeed prevention of sphincter damage, is limited.6 The list is as follows:

- Large baby (4kg or more birthweight)

- First vaginal delivery

- Instrumental delivery, particularly with forceps

- Occipito-posterior position

- Second stage duration more than one hour

- Induced labour

- Epidural anaesthesia

- Shoulder dystocia

- Midline episiotomy

It scarcely needs to be pointed out that little can be done about such factors as the size of the baby, the position of the fetal head or birth order. Prolonged second stage goes hand in hand with instrumental delivery and use of epidural anaesthesia is common. The technique of episiotomy, however, may be a factor that can be modified to reduce the risk of sphincter disruptions. ACHS data for young women having their first vaginal birth reveal that about 27 per cent will have an episiotomy with no associated tear, with an additional six per cent having an episiotomy complicated by a tear. A study has revealed that the greater the angle of the episiotomy away from the midline, the lower the rate of sphincter injury.7 Thus, if episiotomy is required and sphincter disruption is a high risk (large baby, malposition, prolonged second stage), then the cut should be made as laterally as possible.

Identifying sphincter injuries

It is important not to miss a third or fourth degree perineal injury. All women should have a careful examination after vaginal birth as this can double the detection rate of OASIS and potentially reduce the risk of long-term morbidity.8 It is important to explain to women the purpose of examination and the reasons it is being performed. Evaluation requires good exposure and lighting, and analgesia if required. Rectal examination should be performed whenever any perineal injury is apparent, as ‘buttonhole’ injury to the rectal mucosa has been reported even when the sphincter complex appears to be intact. Careful clinical examination has been shown to be as accurate as endoanal ultrasound in the diagnosis of sphincter injury.9

Repair of third and fourth degree tears

If a sphincter injury has been diagnosed, it is important that someone experienced in the management of such injuries becomes involved in the repair. This is usually an obstetrician or suitably experienced registrar who, if not performing the repair directly, at least supervises the repair carefully. Partial sphincter injuries (that is, those classified as 3a injuries) may be repaired in the delivery suite, provided there is good exposure and lighting, and analgesia is sufficient for a good result and for the woman’s comfort. However, most institutions now recommend that repair of more severe injuries should be performed in an operating theatre setting for optimal results.

The repair procedure should be covered with antibiotics. Although there are no formal trials of antibiotic cover for such repairs, infection is a well-known risk for wound breakdown and fistula formation and strenuous efforts should be made to avoid this.10,11 Recognised regimes include single intravenous doses of both cephazolin 1g and metronidazole 500g, or a single intravenous dose of ticarcillin-clavulanate 3.1g. Where penicillin allergy is known or suspected, then single intravenous doses of both lincomycin 600mg and gentamicin 240mg may be considered. The ends of the sphincter need to be identified, and this is not necessarily easy. Often an end will retract into the mass of perineal muscles and can be difficult to identify, hence the benefits of experience in repair. Adequate analgesia allows relaxation of the sphincter muscle and reduces tension at the time of repair. There is considerable debate about the use of either ‘end-to-end’ repair or ‘overlapping’ repair of the sphincter. To say that there is disagreement about the merits of each method of repair is an understatement. This debate is well summarised in the RCOG Green Top Guideline8, and we précis this here:

Review of trials involving a relatively small number of women (less than 300 in total) revealed no differences in perineal pain, dyspareunia, flatus incontinence or faecal incontinence between the two methods of repair at one year post-delivery. However, the ‘overlap’ repair was associated with a lower incidence of faecal urgency symptoms and a lower ‘anal incontinence score’ in the overlap group. There was no overall difference in quality of life (QoL) scores between women in the two groups. It was conceded that experience of the surgeon was not taken into account by the studies, and so the reviewers can make no recommendation of one method over another. A randomised controlled trial from Canada, published in July of 2010, compared 75 injuries repaired using the ‘end-to-end’ technique with 74 repairs of the ‘overlapping’ type.12 The authors concluded that although end-to-end repair was associated with higher rates of faecal and flatus incontinence, the differences were not significant. It is thus difficult to make a firm recommendation on the method of repair of the sphincter. Perhaps the most important issue is training and experience of the surgeon performing the repair.

Choice of suture material includes such monofilaments as PDS or Maxon, usually in 2/0 size, although there are no studies directly comparing suture materials.13 Correct identification and repair of injuries to the rectal mucosa is absolutely critical to a good result. With retraction and good lighting, the apex is identified and secured with a running 4/0 Monocryl suture or interrupted sutures with the knot tied in the anal canal. This suture continues to the anal verge. The sphincter ends are then identified and repaired. Sutures to the muscle should be interrupted and the knot buried under the transverse perineal muscle layer to minimise discomfort

Immediate postnatal management

Although the use of antibiotic prophylaxis at the time of the repair procedure is clearly indicated, there is less evidence to support the use of antibiotics during the healing phase. However, there is little adverse effect from this practice and infection is a major problem so oral antibiotics such as Augmentin®, or clindamycin where penicillin allergy is a factor, should be considered. As usual, local application of cold packs and oral anti-inflammatory medications may provide additional comfort. Suppositories should be avoided, if only because their use may be blamed by the patient if complications arise.

To reduce straining during defaecation and consequent damage to the repair, agents such as lactulose 20ml morning and night, or a sachet of something like Fybogel two or three times daily may be commenced and used for one to two weeks post-delivery.14 The aim is avoid straining at stool, but not to have a loose stool, which may be cause difficulty with continence. It is important that women remain well-hydrated and shower at least twice a day to improve perineal comfort. Initial referral to a physiotherapist skilled in this area is very beneficial, so that women can be educated about pelvic floor care and specific techniques for defaecation.

Medium-term management

Most maternity services now recognise that third- and fourth-degree perineal injuries are major events for women and careful follow up is important. Fortunately, and provided the injury is correctly diagnosed and promptly managed, most women will make a full and complete recovery with no adverse symptoms or continence difficulties.13,15,16

At the six-week postnatal visit, women need to be carefully questioned about control of flatus and bowel motions, including urgency symptoms. Women are often reluctant to volunteer these symptoms, due to social taboo, and thus ensuring follow up within a clinic where they will specifically questioned is paramount. Heavy vaginal discharge can indicate the presence of a fistula, which can be small and difficult to spot. Urinary continence should be asked about and some assessment made of pelvic floor tone and comfort, including whether intercourse has occurred and any problems associated with it. Women who report ongoing pain or problems with continence need careful review and investigation, ideally with endoanal ultrasound and possibly anal manometry studies. As many as one-third of women who have their sphincter injuries identified and correctly repaired will have persisting defects on endoanal ultrasound examination, but the significance of such a finding remains unclear.17

Sexual dysfunction is common in women with urinary and faecal incontinence, but even without these symptoms there is a high rate of dyspareunia following OASIS. This is often due to scarring and perineal revision may be required at a later date, sometimes with the help of a plastic surgeon to rebuild the perineum with flap grafts. The role of levator spasm and vaginismus is also an important factor especially following a difficult and painful delivery. The role of the pelvic floor physiotherapist for myofascial release of the trigger points cannot be underestimated and it is important to emphasise to the woman that this treatment will take time. Sexual counselling can also be important to help the couple through this difficult time.

Pregnancy after an injury

Women who have had a severe perineal injury will naturally be apprehensive about their next delivery. To date, there are no published prospective studies to offer guidance and this is an area ripe for a large, controlled trial. In general, women who have made an uncomplicated recovery and who have remained asymptomatic can consider vaginal birth subsequently. In terms of the conduct of such a birth, it is worth paying attention to the risk factors previously identified. Consideration should be given to the likely birthweight of the baby and to the potential effect of adverse positions of the head, in particular occipito-posterior positions. If episiotomy is used, to make sure it is a wide lateral one, bearing in mind there is no real evidence that ‘prophylactic’ episiotomy is of value and that routine episiotomy in fact increases the risk of OASIS.

Women who are symptomatic or who experienced transient symptoms after delivery should be offered elective caesarean delivery should they wish.18 It is obviously a regrettable situation if a woman who suffered an extremely unpleasant sphincter tear in her first birth, and who has made a suboptimal recovery and remains symptomatic, is then encouraged to have another vaginal birth only to end up in the same situation or with exacerbation of her symptoms. The RCOG Green Top Guidelines recommend that elective caesarean section should be offered to all women who have sustained an OASIS if they remain symptomatic, experienced transient symptoms following delivery or in whom the endoanal ultrasound shows more than one quadrant affected or abnormal endoanal manometry on testing.8

In the end, we recommend that all women who have a sphincter injury be made aware that the choice for elective caesarean section next time will not be argued over should they wish. Women should be aware that there is little or no high-quality prospective evidence to guide practice in subsequent delivery and patient wishes and satisfaction should be paramount, to try to salvage some dignity and enjoyment of the next birth.

Colorectal treatment of anal incontinence is improving and surgical treatment for faecal incontinence once a woman’s family is complete is now more successful, especially with the use of sacral nerve stimulation even in the presence of anal sphincter defects. Early referral is recommended if conservative treatment with pelvic floor physiotherapy has not relieved her symptoms.

Useful resource: http://www.aafp.org/afp/2003/1015/p1585.pdf.

References

- Donnelly VS, Fynes M, Campbell D, et al. Obstetric events leading to anal sphincter damage. Obstet Gynecol 1998; 92: 955–61.

Sleep J, Grant A, Garcia J, et al. West Berkshire perineal management trial. BMJ 1984; 289: 587–90. - Robson S, Laws P, Sullivan EA. Adverse outcomes of labour in public and private hospitals in Australia: a population-based descriptive study. Med J Aust 2009; 190: 474–7.

- Sultan AH, Kamm MA, Hudson CN, et al. Anal-Sphincter disruption during vaginal delivery. N Engl J Med 1993; 329: 1905–11.

- Thakar R, Sultan AH. Management of obstetric anal sphincter injury. The Obstetrician and Gynaecologist 2003; 5: 72–8.

- Williams A, Tincello DG, White S, et al. Risk scoring system for prediction of obstetric anal sphincter injury. BJOG 2005;

112:1066–9. - Eogan M, Daly L, O’Connell PR, O’Herlihy C. Does the angle of episiotomy affect the incidence of anal sphincter injury? BJOG 2006; 113:190–4.

- Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG). Management of third and fourth-degree perineal tears following vaginal delivery, Guideline No. 29. London: RCOG Press; 2007. Andrews V, Sultan AH, Thakar R, Jones PW. Occult anal sphincter injuries: myth or reality? BJOG 2006;113:195–200.

- Buppasiri P, Lumbiganon P, Thinkhamrop J, Thinkhamrop B. Antibiotic prophylaxis for fourth–degree perineal tear during vaginal birth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;(4):CD005125.

- Sultan AH, Monga AK, Kumar D, Stanton SL. Primary repair of obstetric anal sphincter rupture using the overlap technique. BJOG 1999; 106: 318–23.

- Farrell S, Gilmour D, Turnbull G, et al. Overlapping compared with end-to-end repair of third- and fourth-degree obstetric anal sphincter tears: a randomised controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol 2010; 116: 16–24

- Williams A, Adams EJ, Tincello DG, et al. How to repair an anal sphincter injury after vaginal delivery: results of a randomised controlled trial. BJOG 2006;113: 201–7.

- Mahony R, Behan M, O’Herlihy C, O’Connell PR. Randomised clinical trial of bowel confinement vs. laxative use after primary repair of a third degree obstetric anal sphincter tear. Dis Colon Rectum 2004; 47: 12–17.

- Malouf AJ, Norton CS, Engel AF, et al. Long term results of overlapping anterior anal sphincter repair for obstetric trauma. Lancet 2000; 355: 260–5.

- Fernando RJ, Sultan AH, Kettle C, et al. Repair techniques for obstetric anal sphincter injuries: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol 2006; 107: 1261–8.

- Fitzpatrick M, Behan M, O’Connell R, O’Herlihy C. A randomized clinical trial comparing primary overlap with approximation repair of third degree tears. Am J Obstet Gynaecol 2000: 183: 1220–4.

- Fynes M, Donnelly V, Behan M, et al. Effect of second vaginal delivery on anorectal physiology and faecal continence: a prospective study. Lancet 1999; 354: 983–6.

Leave a Reply