While each country’s health system and environment differs, an international review of the literature can illuminate the homebirth debate.

When The Economist devotes two pages to homebirth, you know something is definitely up. To put this in context, the dumping of Kevin Rudd scored less than a page. The article was triggered by the conviction and jailing of an Hungarian midwife, Agnes Gereb, following the death of a baby in a homebirth gone wrong. The article began:

‘A risky and self-indulgent eccentricity, or a return to natural obstetrics? A medical and political row rages between supporters of homebirth, many of them midwives and expectant parents, and its detractors, many of them doctors. Start telling women where they may or may not give birth, with hints that their choice may endanger their child’s life, and the gloves come off.’

The homebirth feature, running in the first week of April 2010, captured a new spirit of combativeness between the groups. As The Economist put it, ‘many doctors think they are trying to curb a bunch of lentil-munching fanatics,’ while ‘the homebirthers decry grasping, bossy doctors.’ Ultimately, the fundamentals of the issue as seen in the public domain were pinned down nicely:

‘Giving birth at home may be safe most of the time, but when things do go wrong, they are more serious. In hospital more things go wrong because intervention is more common, but the complications are less likely to be lethal or to cause permanent damage.’

Considering that homebirth constitutes less than one per cent of births in Australia, it commands a disproportionate amount of media time and makes the ‘blogosphere’ ring like a bell.

When an American celebrity, former talk-show host Ricki Lake, funded and released a documentary that prominently featured homebirth, ‘The Business of Being Born’, the American Medical Association (AMA) censured her with the support of the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG). The mixture of big medicine and big Hollywood was explosive. Ms Lake delivered her second child at home, ‘in her bathtub’. State legislation purportedly outlawing homebirth was discussed, and the backlash from homebirth supporters was predictable and loud.

Australia had its own celebrity homebirth frenzy when Dannii Minogue embarked on an unsuccessful attempt to deliver her first child at home. As the Sydney Morning Herald put it, ‘Dannii Minogue and her new son are resting in a Melbourne Hospital after the pop star’s plans for a homebirth were scrapped due to complications.’ Ms Minogue had an intrapartum transfer from home to the Royal Women’s Hospital, something that occurs in about a third of planned homebirths.

All of the media coverage at the time prompted Prof Cathy Warwick, general secretary of the UK Royal College of Midwives, to lash out at what she called a ‘calculated campaign against homebirths, intended to scare women into believing it was unsafe’ (reported in The Guardian, 29 December, 2010). When asked during a subsequent radio interview exactly who was spreading the ‘anti-homebirth message’, she memorably replied:

‘Researchers from across the world, who seem to be collaborating with the media … [are] publishing studies which suggest homebirth is not safe and give the impression that hospital birth, on the other hand, is completely safe.’

How does this extraordinary claim stack up? And who is claiming hospital birth is ‘completely safe’? A recent meta-analysis of planned homebirth included peer-reviewed English-language studies from Western countries and assessed a range of intrapartum interventions as well as maternal and perinatal outcomes1. Only 12 studies of suitable quality were identified, though this still allowed comparison of 34 2056 planned homebirths with 20 7551 planned hospital births. The homebirth group underwent fewer interventions (neuraxial anaesthesia, episotomy and operative deliveries) and had a lower rate of reported infectious morbidity, anal sphincter injuries and haemorrhage. However, the overall neonatal death rate was almost three times higher for babies born without congenital anomalies in the homebirth group (0.15 per cent versus 0.04 per cent, OR 2.87, 95 per cent CI 1.32 – 6.25).

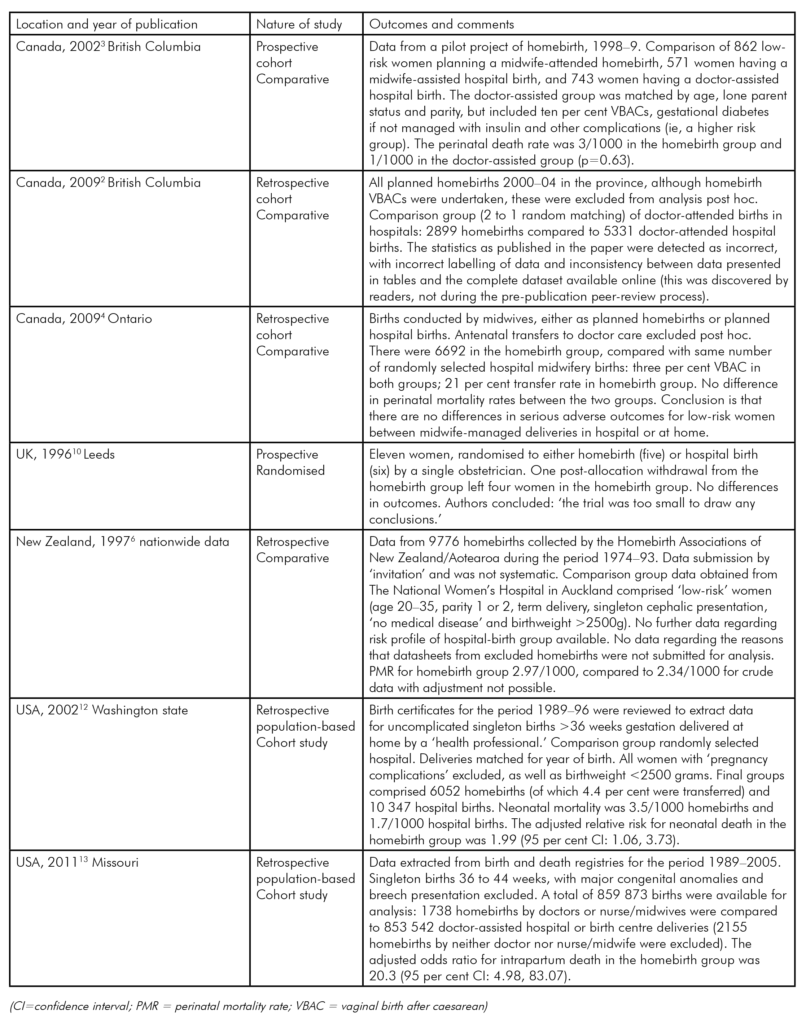

Homebirth accounts for less than two per cent of births in Canada2 although it is supported by the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada (see p55). Canada has many geographical similarities to Australia, with ‘the rugged geography and mixed weather conditions … [presenting] unique challenges for homebirth.’2 In Ontario, two midwives attend homebirths and random practice audits are undertaken by the College of Midwives of Ontario. Three published studies address homebirth in Canada. One compared 6692 midwife-assisted homebirths with the same number of midwife-assisted ‘low-risk’ hospital births2, and reported no difference in perinatal mortality rates between the groups.

Two studies from British Columbia, the first a smaller study from a homebirth pilot program3, the other a larger study covering the period 2000–044, revealed a higher rate of perinatal death in the homebirth group, although this did not reach statistical significance. The second paper, as published4, had major errors in the reporting of statistics including incomplete data and mislabelling of data. These errors were identified by readers, not during the peer-review process, making interpretation difficult.

Homebirth appears to be more common in New Zealand, although accurate incidence data remain unpublished due to the methods by which statistics are collected. Midwives attending homebirths do not require additional training or certification and any midwife can work in independent practice as a lead maternity carer (LMC). The system of care is described as follows:

‘Registered midwives practice autonomously and can choose to birth women in any setting available to them and for which they have an access agreement, for example,

at home, in a primary birthing unit, or in a secondary

or tertiary-level hospital. Midwives are required to give information about the options available in their area to assist [women] to make an informed decision. The choice is driven by the woman rather than the midwife, however, the midwife guides the woman depending on the health of the woman and her baby.’5

A single study, published in 1997, reviewed selected self-reported data from the period 1973–93 and reported a perinatal mortality rate no different from a ‘selected’ comparison group of women delivering in hospital6. No more recent data were available at the time of writing.

The rate of homebirth in the UK is approximately 2.8 per cent7. The joint statement regarding homebirth by the Royal College of Midwives (RCM) and the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG)8, (see p55 for a review), supports homebirth, stating:

‘There is no reason why homebirth should not be offered to women at low risk of complications and it may confer considerable benefits for them and their families.’

Only two studies from the UK – a study of 202 general practitioner homebirths compared to 185 hospital births conducted between 1978–839, and a very small study of 11 women conducted in 199410 – have reported comparative data, so claims that the safety of homebirth in the UK are backed up by data are difficult to support using recent data from the published literature.

Homebirth is rare in the USA, with a rate of approximately 0.6 per cent11, and is opposed by ACOG and AMA. The ACOG statement on homebirth is reviewed in this issue of O&G Magazine (see p56). Two studies of planned homebirths, one from births from 1989 to 1996 in Washington state12, the other from 1989–2005 in Missouri13, both reported increased relative risks for perinatal deaths in the planned homebirth groups. All of the above papers are summarised in Table 1.

It is worth discussing two oft-quoted papers that were not included in Wax and colleagues’ systematic review1, owing to the poor quality of the data available for inclusion in the meta-analysis. The first was by Johnson and colleagues, published in the BMJ in 200514. That paper used the North American Registry of Midwives, a body providing a professional credential for direct-entry midwives who attend planned homebirths. Towards the end of 1999, the Registry made participation in the study mandatory and over 400 midwives duly submitted data on the outcome of homebirths for women due to deliver in the year 2000 in the USA and Canada. These submissions resulted in data from 5418 women planning homebirths being available for study. Comparison data were obtained from the set of all term singleton cephalic births in the USA that year, a cohort of well over three million. A comparison of intervention rates between the planned homebirths and the year’s overall birth cohort revealed the homebirth group had lower rates of ‘intervention’ (episiotomy, instrumental delivery and caesarean section). Recognising that this comparison included high-risk pregnancies, perinatal mortality was compared with a number of published studies of ‘low-risk births’. The rate in the planned homebirths (after exclusion of babies with congential abnormalities) was 1.7 deaths per 1000 births, but studies provided for comparison were published from as long ago as 1969. The most recent comparison group was from a Canadian study using data from the period 1998–9, and the perinatal mortality rate in that study was 1.4/1000 births, considerably lower than the homebirth group under study.

The second paper, published in 2008 by Mori and colleagues15, details a population-based cross-sectional study focusing on ‘booked homebirths’. The study extracted data from published sources and extracted data on perinatal death from national inquiries. The authors begin their conclusion with a stark warning: ‘the results of this study need to be interpreted with caution due to inconsistencies occurring in the recorded data.’ The study found that rates of intrapartum fetal death did not improve over the course of the study period, and that the rate of such deaths was high in women transferred to hospital during attempted homebirth, suggesting in effect that the mortality was counted in the hospital statistics where the women ultimately ended up, rather than in the group who actually delivered at home. Using the authors’ words:

‘Thus, although those women who had intended to give birth at home and did so had a generally good outcome, those requiring transfer of care appeared to do significantly worse and indeed had IPPM rates well in excess of the overall rate. It is not possible to tell from the available data when transfer occurred, that is during pregnancy or at labour onset.’

Ultimately, it seems unlikely that any data will have any impact at all on the debate regarding homebirth. The reason for this is well-illustrated in an academic editorial from the Journal of Perinatal Education, published in 2010:

‘For me, the decision to give birth at home was not only a rational, evidence-based one, it was also an emotional, even instinctive one. I knew in the core of my being that I could give birth without drugs and without routine interventions – after all, hadn’t millions of women been doing so for eons?’16

In contrast, Chervenak and colleagues17 appeal to the ethical principles of patient autonomy and beneficence (acting to serve the best interests of the patient) to argue:

‘The immutable truth is that planned homebirth imposes unnecessary increased risk of neonatal mortality and morbidity and perinatal mortality. The pregnant woman is ethically obligated to prevent these clinical risks by accepting hospital-based delivery.

‘The obstetrician’s ethical and clinical obligations to the pregnant, fetal, and neonatal patient regarding planned homebirth include an adequate disclosure of neonatal mortality and morbidity risks and perinatal mortality risks specific to healthcare in the United States, directive counseling in the form of recommending against planned homebirth.’

I leave the last word to The Economist:

‘A definitive statistical answer to the relative perils of home and hospital births is unlikely. Randomized trials, which are the gold standard in medical research, will be tricky to impossible: women are unlikely to accept a researcher’s arbitrary instruction about where they should give birth. As with many other aspects of child-rearing, birth will come down to parental disposition – whether for a hospital’s bright lights and plentiful pain relief, or for the familiar comforts of home.’

Table 1. Summary of homebirth studies in Canada, the UK, New Zealand and the USA:1990–2011.

References

References are available from the author upon request.

[…] quickly forgot that she was one of their own and began a media campaign to label midwifery as “risky and […]

[…] quickly forgot that she was one of their own and began a media campaign to label midwifery as “risky and […]

[…] quickly forgot that she was one among their very own and commenced a media marketing campaign to label midwifery […]