Cervical neoplasia in pregnancy is often an emotionally charged, challenging situation in which the risks of all the various options available to the woman need to be considered and carefully explained.

Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and pregnancy

Five per cent of pregnant women will develop abnormal cervical cytology. The assessment and management of these women can present unique challenges. There is no evidence to suggest that the natural history of cervical neoplasia is altered by pregnancy and, therefore conservative management of non-invasive cervical lesions is considered safe. 1 Biopsy and treatment can usually be safely delayed until after delivery.

Principles of management

The primary task of the colposcopist is to exclude invasive cervical disease. This is not always easy since the physiological changes of pregnancy make colposcopic assessment difficult. In addition, fewer women are now undergoing colposcopy in pregnancy. This is most likely due to a decrease in opportunist cervical screening in the first trimester, and the recognition that colposcopic assessment can be deferred until after delivery for most women with low-grade squamous abnormalities. Fewer colposcopists have extensive experience and expertise in colposcopic assessment in pregnancy and gynaecologists are advised to seek out the opinion of an expert colleague if they have concerns.

Referral for a colposcopy in pregnancy will usually follow similar guidelines as for the non-pregnant woman (see Table 1).1,2 The asymptomatic pregnant woman with cervical cytology suggestive of a productive HPV infection does not require immediate investigation and subsequent management can be safely postponed until after delivery.3 However, anxiety in the pregnant woman may lead to referral for reassurance. Several large series confirm that regression rates are high for low-grade abnormalities in pregnancy and that asymptomatic woman with such Pap smears are very unlikely to harbour occult invasive disease.3

Women with cervical abnormalities suggestive of high-grade squamous lesions do require colposcopic assessment to exclude invasive cervical cancer. The clinician needs to be reminded that a small percentage of women with cervical cytology suggesting a high-grade squamous abnormality will harbour invasive cervical cancer. Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) 2 and 3 can be managed conservatively during pregnancy, but most series suggest a high likelihood of persistence postpartum and treatment is usually required after the pregnancy is completed.

Table 1. Management of an abnormal Pap test during pregnancy.

| Pap smear results | Suggested management |

| PLGSIL or LGSIL | Women should be managed in a similar manner as for the non-pregnant women with a repeat Pap test in 12 months |

| High-grade squamous lesions and possible high-grade squamous lesions | Refer to colposcopy/exclude invasive disease |

| All glandular lesions | Refer to colposcopy |

| Concerning cervical appearance/persistent postcoital bleeding. | Refer to colposcopy |

It is also important to remember that a woman with unexplained persistent bleeding in pregnancy, especially postcoital, should have a speculum examination, cytology and colposcopy, if warranted.

Advice for the colposcopist

A significant degree of experience and technical expertise is required to perform colposcopy in pregnancy. The cervix is hypertrophied and hyperaemic and there is markedly increased vaginal laxity. Women should be reassured concerning the safety of colposcopy in pregnancy and, as with any surgical procedure, consideration should be given to the likely challenges of the examination before proceeding. A large (broad and long) Cusco speculum is usually necessary and retraction of the vaginal walls, using a glove finger or condom with the end removed, is usually more comfortable for the women than a vaginal wall retractor.

There are several pitfalls for the less experienced colposcopist. Deciduosis in pregnancy can have an appearance suggestive of malignancy and the features of squamous metaplasia may be exaggerated, as are vascular changes. The goal is to exclude malignancy and this may or may not require a targeted biopsy. Biopsy is considered relatively safe in pregnancy, but is not necessarily considered part of standard management. Cervical biopsy can usually be avoided in pregnancy and the experienced clinician will be more comfortable with making a ‘clinical’ diagnosis of exclusion of invasive disease. A second opinion from a more experienced colleague can be most reassuring for the clinician and the patient, and should be sought whenever the colposcopist is uncertain about the appearance of the cervix.

The diagnosis of a frank malignancy must be confirmed by target biopsy. The more challenging situation for the colposcopist is when early invasive disease is suspected. In this situation a larger biopsy is required, which may take the form of a wedge biopsy, needle diathermy or knife cone, or diathermy loop excision. Many surgeons advocate use of additional haemostatic sutures or cerclage to reduce the significant risk of haemorrhage and subsequent pregnancy loss. These procedures are usually carried out under general anaesthesia, in hospital. Many authorities suggest that such surgery is performed between 12 and 20 weeks, but this advice is based on practices that predate the widespread use of ultrasound for pregnancy dating and viability. The precise risks for the mother and pregnancy are difficult to define, with only small case series available with varying results, but obviously pregnancy loss and significant haemorrhage can occur.4

Cervical ACIS in pregnancy

Rarely a woman is discovered with adenocarcinoma in situ (ACIS) either on cytology or biopsy in pregnancy. Cytological interpretation and colposcopy have limited roles in the management of the non-pregnant women with ACIS and the physiological changes of pregnancy only heighten the deficiencies of these tools. Australian data suggest that at least 16 per cent of women with ACIS on Pap will harbour an invasive cancer, the majority cervical. Only a proportion of these lesions will be obvious at colposcopy.5 Guidance as how to best care for women in this situation is scarce, and care has to be individualised. Expert cytologic review of the referral Pap smear and biopsies may be most helpful prior to proceeding to excisional procedures in pregnancy. A large excisional biopsy may be required in the second trimester in order to determine the extent of the lesion and inform subsequent care, or this may be delayed until the postpartum period, depending on the gestation the diagnosis is made.6,7

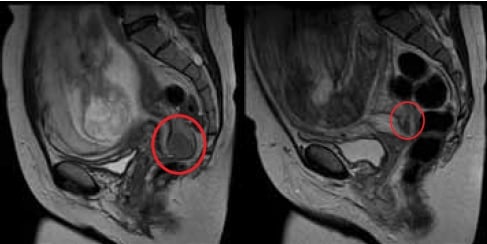

MRI image of cervical squamous cell carcinoma (ringed) diagnosed 18–20 weeks (left) and taken at 34 weeks after three courses of neoadjuvant chemotherapy (right). Images courtesy Robin Harle, Royal Hobart Hospital.

Key points

- Colposcopy in pregnancy may be difficult.

- The main aim of colposcopy in pregnancy is to exclude invasive cancer.

- Seek a second opinion when there is uncertainty about the diagnosis.

- Cervical biopsy is not usually necessary in pregnancy.

- Treatment of CIN2/3 should be deferred until after pregnancy.

Invasive cancer of the cervix in pregnancy

When invasive cervical cancer is suspected on Pap smear or colposcopy or confirmed by biopsy in the pregnant woman, the further assessment and management should be carried out by a certified gynaecologic oncologist.The incidence of invasive cervical cancer in pregnancy is around 1/10 000 and is declining. The gestational age at diagnosis, tumour type, stage and extent of disease and the woman’s wishes will influence advice and care. A recent international consensus meeting agreed that: ‘the limited experience with an invasive cervical cancer diagnosis in pregnancy renders every treatment proposal other than established standard therapy for the non-pregnant patient experimental.’8 Certainly, when continuation of the pregnancy is desired, women should be informed of the ‘experimental nature’ of the cancer treatment and associated risks for her and the pregnancy.

Women with FIGO stage IA1 (confined to the cervix with <3mm invasion) disease can be treated by a shallow cone biopsy in the second trimester.9 For more advanced disease, diagnosed in the first or second trimesters, staging is advised. Pelvic examination remains the basis of FIGO staging for cervical cancer, however, other techniques may be considered to inform on the extent of disease and assist decision-making. Pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is widely used in pregnancy and thought to be safe. Although this will inform of the size and local extent of the tumour, MRI is a poor predictor of lymph node status. Since lymphatic spread is a major determinant of prognosis it has recently been proposed that when pregnancy-sparing treatment is preferred, pelvic lymphadenectomy (either extra peritoneal or laparoscopic) should be considered in the second trimester to define lymph node status.9,10 It is also suggested that sentinel node biopsy can be safely performed in pregnancy and this may play a role in the future.10 For high-risk node positive disease it is then advisable to terminate the pregnancy via hysterotomy and treat the women aggressively with standard chemoradiation.

For women with operable node negative cancers (FIGO ≤IB1: confined to the cervix and less than 4cm is diameter) there are several options. Trachelectomy has been performed in pregnancy, although associated with significant haemorrhage and pregnancy loss. Most frequently, a radical caesarean hysterectomy is considered once fetal maturity is reached.10,11 The use of neoadjuvant (NACT) platinum chemotherapy is reported in the literature to shrink disease and theoretically minimise metastatic spread while awaiting fetal maturity.12 Timing of the delivery should be decided in conjunction with neonatal and obstetric advice.

NACT may also be considered for more bulky higher stage disease (≥IB2) while awaiting fetal maturity, subsequent caesarean delivery and definitive treatment with chemoradiation. Vaginal delivery is seldom considered an option unless the cervix is free of tumour. Fatal recurrences in episiotomy scars have been reported.

Most gynaecologic oncologists rarely encounter pregnant women with cervical cancer. It is often a difficult situation in which the risks of all the various treatment options available need to be fully considered and carefully explained. Broad multidisciplinary discussion involving histopathologists, oncologists, neonatal and obstetric colleagues is important to assist the lead clinician and the individual woman.

Key points

- When invasive cervical cancer is suspected in the pregnant woman, the further assessment and management should be coordinated by a certified gynaecologic oncologist.

- Discussion across multiple disciplines is frequently necessary to fully inform the women of her choices.

References

- Flannelly G. The management of women with abnormal cervicalcytology in pregnancy. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol.2010;24(1):51-60.

- Screening to Prevent Cervical Cancer: Guidelines for the Managementof Asymptomatic Women with Screen Detected Abnormalities. AustralianGovernment. NHMRC ISBN: 0 642 82714 1.

- Wetta LA, Mattthews KS, Kemper ML et al. The Management of CervicalIntraepithelial Neoplasia During Pregnancy: Is Colposcopy necessary? JLow Genit Tract Dis 2009; 13(3): 182-185.

- Demeter A et al. Outcome of pregnancies after cold-knife conizationof the uterine cervix during pregnancy. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol.2002;23(3):207-10.

- Mitchell HS. Outcome after a cytological prediction of glandularabnormality. ANZJOG 2004 Oct;44(5):436-40.

- Lacour RA, Garner EI, Molpus KL et al. Management of cervicaladenocarcinoma in situ during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol.2005;192(5):1449-51.

- Griffin D, Manuck TA, Hoffman MS. Adenocarcinoma in situ of thecervix in pregnancy. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;97(2):662-4.

- Amant F, Van Calsteren K, Halaska MJ et al. Gynaecological Cancersin Pregnancy: Guidelines of an International Consensus Meeting. Int JGynaecol Cancer. 2009; 19: S1-S12.

- Yahata T, Numata M, Kashima K et al. Conservative treatment of stageIA1 adenocarcinoma of the cervix during pregnancy. Gynecol Oncol.2008 Apr;109(1):49-52.

- Amant F, Van Calsteren K, Halaska MJ, Beijnen J, et al. GynaecologicalCancers in Pregnancy: Guidelines of an International ConsensusMeeting. Int J Gynaecol Cancer. 2009; 19: S1-S12

- Amant F, Brepoels L, Halaska MJ, Gziri MM, Calsteren. Gynaecologic Cancer complicating Pregnancy: An Overview. Best Pract Res ClinObstet Gynaecol. 2010 Feb;24(1):61-79.

- Li J, Wang LJ, Zhang BZ et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy with paclitaxel plus platinum for invasive cervical cancer in pregnancy:two case report and literature review. Arch Gynecol Obstet.2011;284(3):779-83.

Leave a Reply