The management of single fetal death in a twin pregnancy can be difficult for any obstetrician.

Perinatal mortality in twin pregnancies is approximately five times higher than in singleton pregnancies. If both fetuses die the management is straightforward: delivery by the most appropriate means. Death of one of a twin pair is more challenging. The sequelae for the surviving co-twin may be significant, with risks of demise, premature delivery with its consequences and the risk of neurological impairment. Chorionicity, amnionicity, gestation and potential causation must all be considered when determining appropriate management.

Prevalence

’Vanishing twin‘ is a term that has been used to describe the spontaneous loss of a twin during the first trimester. Around 23 per cent of twin pregnancies diagnosed by ultrasound at six-weeks gestation will be singleton pregnancies by 12 weeks. Bleeding or mild cramping may be noticed in the first trimester, but there are no longer term implications for the pregnancy. Grief for the lost twin may be significant and may need to be addressed.

The loss rate for a single twin during the second and third trimesters varies widely in reported series from 0.5 per cent to 11.6 per cent. Although monochorionic (MC) twins account for 30 per cent of all twin pregnancies they account for most of the fetal losses and the vast majority of adverse neurological outcomes. In several recent series, where accurate data is available, the loss rates for MC versus dichorionic (DC) twins has been reported as 3.9 per cent versus 1.3 per cent, 11.6 per cent versus 5.0 per cent and 6.5 per cent versus one per cent, respectively.

Aetiology

The aetiology of single fetal loss in a twin pregnancy varies by placentation and may be iatrogenic or spontaneous in nature.

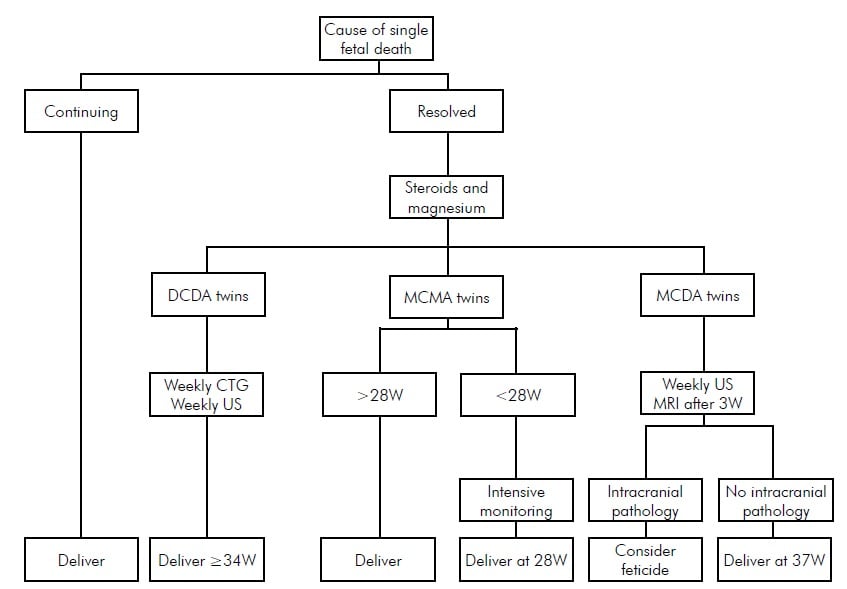

A flowchart outlining treatment guidelines.

Fetal reduction

Single fetal loss in a twin pregnancy may be a consequence of either selective or multifetal pregnancy reduction. The former is performed for a fetal abnormality. The latter may be performed either because it is deemed medically unsafe to proceed with a twin pregnancy or because the parent(s) are unable to cope with a multiple birth.

Dichorionic diamniotic twins

Spontaneous single fetal loss in dichorionic diamniotic (DCDA) twins is usually a consequence of growth restriction, frequently unrecognised. The risk of fetal death increases with the degree of growth discordance, particularly when discordance exceeds 30 per cent.

Pre-eclampsia may result in the loss of one twin only – indeed, loss of the twin is often associated with a short-term improvement in the condition.

Other obstetric complications may result in the demise of only one of a twin pair: placental abruption, gestational diabetes, fetal abnormalities, intrauterine infections and cord accidents.

Monochorionic diamniotic twins

Twin-twin transfusion (TTTS) accounts for at least 50 per cent of all single MCDA twin deaths. Even with extensive and careful surveillance, the risk of sudden fetal death in the third trimester in these pregnancies is 1.2 per cent to six per cent, depending on the level of surveillance. Many have advocated planned early delivery to avoid this complication, but it is controversial.

Selective fetal growth restriction, particularly of the Gratacos type 2 and 3 variants, accounts for significant numbers of fetal deaths in MCDA twins.

Fetal anomalies, which are much more frequent in MC twins than either DC twins or singletons and include particularly cardiac and neurological abnormalities, account for a large proportion of MCDA single twin deaths. Most MC twins, although monozygotic, are discordant for fetal abnormalities.

Twin reversed arterial perfusion (TRAP) sequence is a rare complication of MCDA twins, but whether an acardiac twin can be counted as a fetal death is dubious.

Cord ligation to treat a fetal abnormality or TTTS is obviously lethal to the targeted twin. The procedure isolates the circulation of the co-twin and eliminates the risk of subsequent injury to the survivor. Clinical circumstances will determine if there may have been a pre-existing insult to the fetus.

Laser ablation of communicating vessels to treat TTTS not infrequently results in the demise of one of the twins. If the laser treatment has been successful, the placenta has been effectively dichorionised and there is again no risk of subsequent injury to the survivor, but there may be concerns about a pre-existing insult to the fetus.

Monochorionic mono-amniotic twins

Cord entanglement in monochorionic monoamniotic (MCMA) twins accounts for more than 50 per cent of all losses and may involve one or both twins.

Fetal abnormalities, particularly cardiac and neurological, complicate approximately 25 per cent of all MCMA twins. The abnormalities are frequently lethal, but the twins are usually discordant for the abnormality.

TTTS is less common in MCMA than in MCDA twins, but still contributes to fetal loss.

The same concerns about cord ligation and laser treatment apply to MCMA twins as to MCDA twins.

Complications of fetal death of a twin

Death of the co-twin

The risk of co-twin death following death of a twin after 20 weeks gestation is 12 per cent (95 per cent CI 7-18) for MC twins and four per cent (95 per cent CI 2-7) for DC twins. In a careful systematic review, where there was comparative data, the odds of MC co-twin death were six times higher than DC twins following a single in utero twin death: OR 6.04 (95 per cent CI 1.84-19.87).

Neurological sequelae

Chorionicity is the prime determinant of outcome when one twin dies. DC twins do not share a circulation and so are haemodynamically independent.

MC twins share a circulation with varying combinations of arterio-arterial (AA), arterio-venous (AV) and veno-venous (VV) anastomoses. Death of a MC twin may damage the co-twin by one of two mechanisms. The ’thromboplastin theory‘ proposes that the passage of thrombotic material from the dead to the surviving twin results in thromboses and subsequent neurological injury. The ’ischaemic theory‘ postulates that, immediately before it dies, the twin becomes profoundly hypotensive and partially exsanguinates its co-twin via placental anastomoses, resulting in a period of anaemia, hypotension and hypoperfusion for the twin that eventually survives. There is evidence for both theories, although the latter is probably the more likely explanation in the majority of cases. The neurological injuries may be seen from as early as six days to as late as six weeks after the fetal death. These changes include periventricular leucomalacia, multicystic encephalomalacia, porencephaly, hydrancephaly and microcephaly.

Preterm delivery

The risk of delivery before 34 weeks is higher for MC twins than for DC twins: 68 per cent (95 per cent CI 56-78) versus 57 per cent (95 per cent CI 34-77).

It is difficult to determine the average time between fetal death and the onset of labour as the timing of fetal death is rarely known with any precision. Labour often occurs spontaneously two to three weeks after the recognition of a fetal death, but may occur almost immediately — such as following a placental abruption – or may be delayed for many months.

The timing of iatrogenic preterm delivery is guided by the considerations described in the management discussion below.

Management

Again, the nature of the placentation determines precise management. In all circumstances consideration should be given to the use of corticosteroids to promote fetal lung maturity and magnesium sulphate for neuroprotection. A neonatal paediatric consultation should be arranged and close discussion between the parents, obstetrician and paediatrician over subsequent weeks is essential.

If the live twin is leading, well grown and is in a cephalic presentation, then vaginal delivery may be considered. If the live twin is malpresenting or is growth restricted, or if the dead twin is leading, caesarean section is preferred. Many parents prefer caesarean section regardless of these considerations and this obviously needs to be discussed, taking into account the whole circumstances of the couple.

The development of a coagulopathy if a dead fetus is retained for more than four weeks is remarkably uncommon if the co-twin remains alive. Nevertheless, consideration should be given to perform weekly fibrinogen levels with a platelet count and a partial thromboplastin time after four weeks of confirmed fetal death. A full coagulation screen should be performed before regional analgesia or delivery.

The loss of a twin at any stage of pregnancy is devastating for parents. The psychological issues related to grieving for the lost twin while preparing for the birth of the surviving twin may be profound. The thought of still carrying the retained dead twin and the uncertainty regarding long-term outcome compound the stress of losing a twin. Extensive counselling is often required.

Dichorionic diamniotic twins

Delivery should be delayed until at least 34 weeks gestation, provided there is no obvious continuing pathology that may cause demise of the surviving co-twin. Careful monitoring with serial ultrasound assessments of growth and Doppler blood flow studies as well as regular cardiotocography should be undertaken.

Monochorionic diamniotic twins

When fetal death has been identified in one of an MC twin pair, the neurological injury has already been inflicted. If the fetus has survived that insult, delivery should be delayed as long as possible. This will give the greatest chance of detecting any intracranial pathology. Weekly ultrasounds should be performed, looking for evidence of the changes detailed above. Fetal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has improved detection of these changes. An MRI three weeks after the fetal death is diagnosed is recommended. If intracranial pathology is detected, further neonatal paediatric consultation should be arranged. Many parents will then opt for late feticide when the option is legally available. Some reassurance can be offered to parents if the fetal MRI and serial ultrasounds remain normal for many weeks after the fetal death, but a guarded prognosis is strongly advised.

Doppler assessment of the fetal middle cerebral arteries may indicate anaemia in the surviving co-twin, particularly if it has been performed close to the time of fetal demise. The presence of fetal anaemia in the surviving co-twin is, not surprisingly, associated with a significantly poorer prognosis. The use of a ’rescue‘ fetal blood transfusion has been attempted in several centres, with varying results. It could be considered if fetal demise is of very recent origin and fetal anaemia is evident in the co-twin, but it is unlikely to be of any great value given the timing of causation of these neurological injuries.

Monochorionic monoamniotic twins

The majority of deaths in MCMA twins involve the death of both twins. Occasionally a single MCMA twin may survive the death of its co-twin. The rarity of this circumstance makes it difficult to offer specific advice, but it must be noted that the rate of neurological sequelae in these survivors is extremely high. It may be appropriate, if the death occurred at a very preterm gestation, to delay delivery to allow administration of steroids and magnesium sulphate. Delivery by 28 weeks gestation would be reasonable in these circumstances, although it may be too early at that stage to detect intracranial pathology.

Conclusion

The management of single fetal death in a twin pregnancy can be difficult for any obstetrician. Identification of the cause, monitoring the surviving co-twin, deciding the appropriate time and mode of delivery and counselling in potentially very difficult circumstances can be challenging. Knowledge of the chorionicity is essential to any decision-making process and almost entirely determines the outcome.

Further reading

Dickinson JE. Monoamniotic twin pregnancy: a review of contemporary practice. ANZJOG 2005; 45: 474-478.

Hack KEA, Derks JB, Elias SG et al. Increased perinatal mortality and morbidity in monochorionic versus dichorionic twin pregnancies: clinical implications of a large Dutch cohort study. BJOG. 2008; 115: 58-67. Mahony R, Mulcahy C, McAuliffe F et al. Fetal death in twins. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2011; 90: 1274-1280.

National Collaborating Centre for Women’s and Children’s Health. Multiple pregnancy: the management of twin and triplet pregnancies in the antenatal period. 2011. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Ong SSC, Zamora J, Khan KS, Kilby MD. Prognosis for the co-twin following single-twin death: a systematic review. BJOG. 2006; 113: 992-998. Whittle MJ. Management of a dead twin. The Obstetrician and

Gynaecologist. 2002; 4 (1): 17-20.

Thank you for touching a very important issue and for the scientific information provided.

great job

Thank you much nice info

Very useful information, thanks

Thank you much for this important information

Very nicely presented this information,

Thanks a lot..

Women giving birth to multiples can have babies who are all identical, all fraternal, or a mixture of both. Identical twins or triplets result when a single egg is fertilized that later divided into two or three identical embryos. Identical twins are of same-sex, have the same genetic identity, and are exactly the same. Fraternal twins or triplets. Fraternal twins develop when separate eggs are fertilized by separate sperms. It’s not necessary that fraternal twins or triplets will resemble each other.

Thank you very much for all this information. Lost twin yesterday. Still in womb. Scan this morning to evaluate situation.

Currently managing such a case.. information was helpful.

Thank for the information