Carcinomas of the vulva and vagina are some of the most uncommon. This article discusses diagnosis, staging and treatment options.

Carcinoma of the vulva is uncommon in Australia, with 280 new cases being diagnosed each year or two women per 100 000. It accounts for less than one per cent of all cancers in women. It usually occurs in women between the age of 55 and 75 years old and is associated with irritant conditions such as lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. In younger women it is associated with human papilloma virus (HPV) infection and smoking.

Diagnosis

Vulvar cancers usually present as a raised lump or ulcerated area. In making the diagnosis it is preferable that either a Keyes punch biopsy or a small wedge biopsy, including adjacent normal skin, is performed. Excising the entire lesion may compromise the patient’s care, either by making the site of the lesion difficult to detect due to superior healing of the area or limiting the use of sentinel groin node detection. This is especially true of the smaller lesions. As vulvar carcinoma is often associated with cervical carcinoma (ten per cent), cervical cytology should also be performed at diagnosis.

Management

Surgery remains the key for localised disease. Obtaining a 1cm surgical margin and dissecting down to the inferior fascia of the uro-genital diaphragm is uncommonly associated with recurrence, whereas if the margin is less than this up to 50 per cent will recur locally. The risk of groin node metastases is related to depth of invasion (see Table 1). Usually the ipsilateral nodal group is at risk, except for lesions that involve midline structures such as the anterior labia minora or clitoris, in which case both groins are at risk and need to be assessed.

If the groin nodes are negative then the survival rate is very high. The number of positive groin nodes remains the single most important prognostic factor. The presence of a single nodal metastasis of less than 5mm in diameter still carries a good prognosis compared to more than two groin nodes involved or extracapsular spread of the metastases from the node, where prognosis falls to a 50 per cent five-year survival. Pelvic nodal metastases, the next echelon of nodal spread, are associated with an 11 per cent five-year survival.

Adjuvant radiotherapy to the groin and pelvic nodes is utilised with more than two positive nodes. Where it is not possible to achieve local vulvar clearance, it may also be used in an adjuvant setting or in advanced disease it may the primary treatment modality followed by resection of residual disease. The morbidity associated with radiation to the vulva requires a skilled radiation oncologist to nurse the patient through her treatment; frequently with breaks in the treatment so she can tolerate the complete course.

Sentinel groin node biopsy in vulvar cancer

The standard of care for vulvar lesions of greater than 1mm invasion and in the absence of obvious nodal metastases is a radical vulvar excision achieving at least a 1cm margin, together with either ipsilateral or bilateral groin node dissection, depending on the location of the tumour. As with breast cancer, the concept of detecting the sentinel node in the groin is highly attractive, because of the high morbidity associated with complete node dissection. However, with lesions less than 4cm in size up to 80 per cent of nodes will be negative. The confounding factor is that 90 per cent of women will die if they recur in an undissected groin. So what false negative rate do you accept and at what risk to your patients?

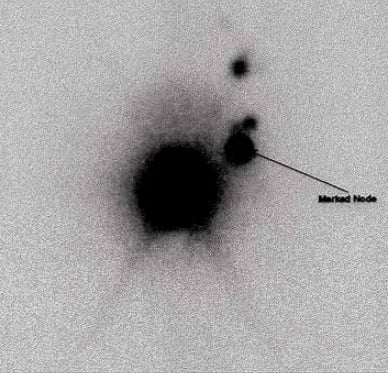

The technique involves the injection of technetium 99-labelled albumin colloid around the lesion then performing scintigraphy with a gamma scan to determine the first draining inguinal lymph node. Vital blue is often used, again injected around the lesion at time of surgery, to assist with identification of the sentinel node together with the use of a handheld gamma probe. It should be reserved for patients with tumours of less than 4cm diameter and in whom no suspicious inguinal lymph nodes are present.

| Depth of invasion | Percentage risk of groin node involvement |

| <1mm | 0 |

| 1.1-3mm | 8 per cent |

| 3.1-5mm | 26 per cent |

| >5mm | 35 per cent |

Carcinoma of the vulva.

Gamma scan one hour post injection of Technichium into the vulva.

Two large studies have shown a false negative rate of 5.9 per cent and 6.9 per cent, while other institutions trying to replicate these studies have reported a 17 per cent false negative rate. It is fair to say this technique is not universally applied in all Australian institutions, but some do use sentinel lymph node examination alone. Some studies have looked at patient reaction to the risk of death associated with recurrence in an undissected groin and suggest patients would not be prepared to expose themselves to that risk, instead opting for a traditional full groin node dissection.

Staging in vulvar cancer

The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) staging was modified, in 2009, to improve the prognostic groupings in terms of survival and to add further sophistication to the staging to reflect the significance of lymph node morphology (see Table 2). Several studies have confirmed that, in comparison to the 1988 staging system, the introduction of differentiation between the number of nodes involved and the presence of extra-capsular spread does stratify survival more accurately.

Carcinoma of the vagina

This is an uncommon cancer, accounting for less than 0.5 per cent of all cancers affecting women. Squamous cell carcinoma is the most common, although clear cell carcinoma secondary to maternal diethylstilbestrol (DES) exposure is probably the most well known among gynaecologists. Survival is not as good as it is for cervical carcinoma with a 70 per cent five-year survival for stage I disease through to 18 per cent for stage IV disease.

The precursors of vaginal carcinoma are not well known – vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia (VAIN) is thought to account for at most five per cent, although approximately 30 per cent of women with a diagnosis of vaginal carcinoma have a history of pre-invasive or invasive cervical carcinoma treated within five years of diagnosis. In the author’s limited experience, VAIN needs to be respected and treated aggressively, particularly in more mature women in whom, if it develops into vaginal carcinoma, it is often resistant to chemoradiation. Prior pelvic irradiation is also a risk factor.

Given that screening is inappropriate for primary detection of this disease, the current screening recommendation is for vaginal vault smears in women with a past history of cervical dysplasia on a two-yearly basis post hysterectomy.

Presentation is usually with either screen detection or painless vaginal bleeding. Most lesions are confined to the upper posterior vagina, but are often missed because of masking of the lesion by the blades of the speculum. In patients who have persistent high-grade smears, but negative colposcopy, an examination of the entire vagina with Lugo’s iodine under general anaesthetic may be appropriate. In postmenopausal women, the use of vaginal oestrogen before the procedure may aid visualisation of the lesion.

Management

The care of patients is very individualised and best done in an oncological centre. Given the incidence of pelvic nodal metastases may be as high as 28 per cent and groin node metastases in the order of 30 per cent in patients with lower-third vagina disease, it is important to treat each case on its merits. Younger patients may benefit from surgery, if possible, otherwise radiotherapy using a combination of pelvic radiation and brachytherapy is widely used. Concurrent cisplatin is the standard in most units.

Post-treatment vaginal stenosis either due to surgery or concomitant radiotherapy remains the largest difficulty for most patients wishing to preserve sexual function. However, bowel and bladder toxicity remain real problems given the high dose of radiotherapy delivered. Survival is poorer than that found with cervical cancer.

Diethylstilboestrol exposure

The use of diethylstilboestrol (DES), a synthetic nonsteroidal oestrogen first synthesised in 1938, is a fascinating story, beginning with its use in prostate cancer in 1941. It was always used in tablet form varying in dose from 5–125mg, not as an injectable as progestogens were. Its initial indication for usage was gonorrheal vaginitis, atrophic vaginitis, menopausal symptoms and postpartum lactation suppression to prevent breast engorgement. In 1947, it was approved for use in pregnancy to prevent miscarriage although it had been used off label for the same indication since the early 1940s. It was recommended to be used at 5mg per day then increased ultimately to 125mg per day by the 35th week of pregnancy. Studies in the 1950s showed that it did not prevent miscarriage, but nevertheless was still prescribed.

In 1970, Herbst and Scully reported on seven young women aged between 15 and 22 years old with clear cell carcinoma of the vagina. All were the child of a woman who had been prescribed DES in pregnancy. The risk of clear cell carcinoma of the vagina was estimated to be one per 1000, with 70 per cent being diagnosed as stage I vaginal adenocarcinomas. This represents a 40-fold increase in risk and is the only known transplacental carcinogen. Other changes occur such as vaginal adenosis in 45 per cent of women and structural changes such as the so called cockscomb, transverse vaginal septum, cervical hypodysplasia or other such changes, in 25 per cent of women. Exposure after 22 weeks was associated with insignificant change.

More recently a report by Hoover et al has suggested that first-generation exposure is associated with infertility, preterm labour, first and second trimester miscarriage, pre-eclampsia, stillbirth and early menopause as well as a higher risk of breast cancer. In males it can be associated with testicular cancer, infertility and urogenital abnormalities in development, such as cryptorchidism and hypospadias.

Women exposed to DES are recommended to have annual colposcopy and vaginal cytology.

Further reading

Hacker NF et al. Individualization of treatment for Stage 1 squamous cell vulvar carcinoma. Obstet Gynecol 1984; 63: 155-162.

Van der Zee et al. Sentinel node dissection is safe in the treatment of early stage vulvar cancer. J Clin Oncol 26:884-89, 2008.

Sentinel node biopsy in patients with vulvar cancer : A Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) study. Levenback CF et al, J Clin Oncol 2009: 27-15s (suppl; abstr 5505).

Herbst , AL, Scully RE Adenocarcinoma of the vagina in adolescence Cancer 1970;25: 745-751.

RN Hoover, et al. Adverse health outcomes in women exposed in utero to diethylstilbestrol. N Engl J Med 2011, 365 (14): 1304-14.

Leave a Reply