Several problems face a standards and training body, such as RANZCOG, in determining what to do with its ageing cohort of Fellows.

The population of Australia topped 21.5 million at the most recent census in 20121, and in 2006, 14.3 per cent of working specialists were over the age of 60 (see Table 1), and data from RANZCOG has and data from RANZCOG has physician workforce was 65 years or older.2

Questions raised about this cohort of Fellows include the following:

- Should they be compelled to retire at a certain age, from some practice, for example, complex surgery, or from all practice?

- Should they be treated differently from younger Fellows, and assessed for CPD in alternative ways?

- Should they be re-certified in the same way as a younger Fellow, as they are practising Fellows of the College, and given that the public has certain expectations of what a specialist O and G can do?

- Should they look to redefine their careers to promote their longevity in the workforce?

Retirement from practice

In the past, it has been traditional for specialist O and Gs to retire at around age 65. Until recent times, hospitals had regulations stipulating that senior consultants had to retire at this age.Since the advent of anti-discrimination legislation and the fact that the average ages of male and female mortality have risen to their highest levels in history1, it now seems likely that many practitioners will work past the age of 65. Coupled with this is the fact that many practitioners do not want to retire, and some may not be in the financial position to do so, given that their nest egg for retirement may have been significantly eroded by the global financial crisis of 2009–10. Thus it seems reasonable to suspect that the cohort of ‘baby boomer’ O and Gs within RANZCOG will continue to work until their late 60s or early 70s. A recent article from the USA highlights the problems inherent in re-credentialing an 80-year-old practitioner for O and G privileges.3

Table 1. Specialists, 1986-2006.

| 1986 | 1996 | 2006 | |

| Total (no.) | 8 973 | 14 950 | 18 259 |

| Rate per 100,000 persons(a) | 57.7 | 84.2 | 92.0 |

| Proportion who were (per cent): | |||

| Female | 16.3 | 24.5 | 28.7 |

| Born overseas | 34.1 | 35.3 | 41.6 |

| Recent arrivals(b) | 3.5 | 5.5 | 8.6 |

| Aged 60 and over | 11.4 | 11.5 | 14.3 |

| Working part time | 10.7 | 13.2 | 17.1 |

(a) Rates calculated using 2006 Census usual resident count.

(b) Recent arrivals are persons who were born overseas and arrived in the five years prior to the relevant Census year.

Source: ABS 2006 Census of Population and Housing.

It is impossible to generalise about the calculation of an individual’s ‘use by’ date, given that humans age in such variable ways. There is no question, however, that as we age our cognitive and physical abilities decline. The problem here can be that doctors do not have the insight to realise their performance is deteriorating.4 It is important also to realise that it is not ageing alone that causes deterioration in performance. Drag et al5 showed that 78 per cent of surgeons aged 60–64 performed within the range of younger surgeons on computerised cognitive testing; 38 per cent of surgeons aged 70 and older compared favourably with the younger surgeons. The authors concluded that older age does not necessarily inevitably preclude cognitive proficiency.

Choudhry et al, in a systematic review on the relationship between the length of clinical experience and quality of care, concluded that physicians who have been in practice the longest may be at risk for providing lower quality care6, which begs the question as to how CPD programs for ageing Fellows should be structured.

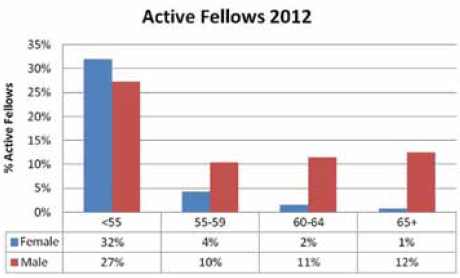

Table 2. Proportion of active Fellows by age bracket.

The problem for a regulatory bodies, such as the Medical Board of Australia (MBA) and RANZCOG, is the variability of practice from doctor to doctor that occurs, such that to make a blanket rule for all practitioners of a certain age is likely to be unfair. In 2009, the MBA introduced mandatory reporting requirements, and Section 140 (c) of National law defines ‘notifiable’ conduct as when a practitioner:

‘placed the public at risk of substantial harm in the practitioner’s practice of the profession because the practitioner has an impairment;’7

Given that it is impossible to generalise, it seems reasonable that consultant O and Gs:

- need to be aware of the ageing process;

- refrain from practice if impaired physically or mentally;

- must ensure a smooth handover of patients under their care on retirement;

- not ignore the ‘shoulder tap’ from a colleague about their performance; and

- recognise their reporting obligations to the Medical Board of Australia with respect to unsafe practice.

Continuing recertification

How then to approach the problem of recertification? Given that it seems clear practice abilities wane with age and that different O and Gs will redefine their scope of practice as they age, it would seem reasonable for RANZCOG to consider the following:

- That appropriate CPD programs be modified or developed to cater for this cohort of practitioners within the College and their varied scopes of practice.

- That an annual health check be done, by the practitioner’s usual medical attendants, with a confidential report being supplied to the College, prior to a practitioner being re-certified. This report should include a letter from the practitioner’s GP detailing any chronic medical conditions likely to affect performance, and should include annual ophthalmic examinations and a hearing test.

That a formal performance review, possibly including a practice visit (this could replace the need for CPD and maintenance of a log book) be carried out. This is in line with suggested policies of other colleges in this area.8 The main problem with this is in designing an equitable system, and resourcing that system, as it would inevitably rely on those doing the practice visits giving their time pro bono.

It would seem reasonable that the work profile of senior staff could change once they reach 60 years of age. At this time, it may be prudent to excuse a senior O and G from the ‘on call’ roster, given that they may be more prone to the effects of fatigue and may not recover as well from a disturbed night’s sleep.

Senior clinicians have a wealth of experience, which should be utilised more than it is. Given that new Fellows of RANZCOG are exposed to less clinical material during their training than in previous times, it seems obvious that senior O and Gs should be more involved in mentoring junior consultants. There are many informal examples of this happening, with senior consultant O and Gs, for example, assisting at complex surgery, but these sorts of arrangements could be extended to labour ward coverage, assistance with operative vaginal birth and other areas of practice as deemed necessary by the junior consultant.

This could happen hand in hand with a phased withdrawal from surgery and a decrease in the complexity of cases done as first operator by the senior consultant. Hospitals and health jurisdictions should be looking to create employment opportunities for such senior staff, or to redefine their clinical roles.

Academic O and G is at a low ebb in Australia at present, and senior staff provide an excellent resource to develop expanded roles in teaching of registrars, resident, medical officers and medical students. Other areas of potential involvement could include research, administration, medico-legal work, medico-political advocacy, College work and hospital governance.9

A career change for ageing doctors?

Christine Jorm, in her recent book Reconstructing Medical Practice10, reviews extensively the problems faced by those in specialist medical practice, areas such as professionalism, and explores why doctors have become alienated from the healthcare system. It seems clear from this book that senior doctors have an opportunity to act as a catalyst for change in how medicine is practised in future. Some reasons for this are the following:

- Senior staff are widely experienced and are often vocal advocates about systems of healthcare, and are less fearful of being ‘punished’ by the health system, for example, by a state department of health, for speaking about a systemic problem in healthcare, and have ‘nothing to lose’.

- They are often respected within their hospitals and their opinions acknowledged.

- They are in a position to influence junior staff, who can also act as agents for change.

- It is a desirable attribute in a RANZCOG Fellow that they actively contribute to their hospital to ensure that patient outcomes and systems of care are the best they can be.11

Therefore, as doctors age, there is an opportunity to engage senior doctors in hospitals. This may be a need to encourage career changes in some of these clinicians and health jurisdictions and universities should look to canvass interests of senior doctors in undertaking teaching, mentoring, research and clinical roles in hospitals, given the dire shortage of clinical academic staff in O and G nationally.

RANZCOG, as the standards and training body overseeing these ageing practitioners, needs to develop reasonable and realistic processes for re-certification of older practitioners; to ensure they are continuing to do CPD appropriate to their current scope of practice; and needs to actively develop programs in this area. It also needs to publicise ageing as an issue confronting the College and attempt to introduce sensible regulation in this area, to

pre-empt anything done by an external regulator.

The College also has an obligation to act as an advocate for older practitioners, to educate the public that age may be no barrier to successful, safe practice and to work constructively with health jurisdictions to look creatively at ways that older doctors can look realistically at a career change, from, say, a busy private practice in O and G, to a career in public medicine, entailing clinical work, teaching, mentoring and research. Doing this may usefully prolong a Fellow’s career span, and will do much to improve the teaching of registrars, residents and medical students.

Summary

Ageing doctors need to be cognisant of the ageing process and their waning powers and should listen to advice of colleagues, friends and spouses about when to retire. They should have an opportunity to re-structure their working life to work ‘smarter’ and in a different scope of practice. They need to influence their professional bodies to develop reasonable systems of re-certification and clearly need to work hard to spend their accumulated superannuation before the Gen Y children inherit it all!

References

- Census data at http://www.abs.gov.au/websitedbs/censushome.nsf/home/census?opendocument&navpos=10 .

- Lobo Prabhu SM, Molinari VA, Hamilton JD,Lomax JW. The aging physician with cognitive impairment: approaches to oversight, prevention and remediation. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2009;17:44554.

- Porreco R AJOG 206(3) p183-186 2012.

- Adler RG, Constantinou C. Knowing—or not knowing—when to stop: cognitive decline in ageing doctors. Med J Aust 2008;189:622-4.

- Drag LL, Bieliauskas LA, Langenecker SA,Greenfield LJ. Cognitive functioning, retirement status and age: results from the cognitive changes in retirement among senior surgeon study. J Am Coll Surg 2010;211:303-7.

- Choudhry NK, Fletcher RH, Soumerai SD. Systemic review: the relationship between clinical experience and quality of healthcare. Ann Intern Med 2005;142:260-73.

- Medical Board of Australia Guidelines for mandatory notifications 2009.

- Collier N Avant Surgeon 2011.

- Waxman B MJA 2012-08-30.

- Jorm C Reconstructing Medical Practice Gower Press 2012.

- RANZCOG statement ‘Attributes of a RANZCOG Fellow’ C-Gen 19 at www.ranzcog.edu.au/statements .

Leave a Reply