The aetiology of stillbirth and neonatal death in New Zealand.

Perinatal death, the death of a baby from 20 weeks gestation in utero through to the first 28 days of life, is a tragic event that is unfortunately far too common. The devastation associated with a perinatal loss cannot be overstated; firstly for the family, but also for the caregivers involved. Despite our best efforts, perinatal death occurs in around one in 100 babies born in New Zealand (NZ). This rate is comparable to other first-world countries, with rates of neonatal death slowly dropping over time with better neonatal interventions, while international rates of stillbirth seem to have remained static.

When the unthinkable happens, we strive for answers – why? All too often the answer seems to be ‘I don’t know’. In 2006, in acknowledgement of the lack of audit into perinatal and maternal mortality in NZ, the Perinatal and Maternal Mortality Review Committee (PMMRC) was created.1 Their annual reports provide an in-depth analysis of known causes and associations with perinatal death in NZ. This valuable tool can highlight areas in need of further research or areas of care that can be improved, with the ultimate aim of reducing perinatal death.

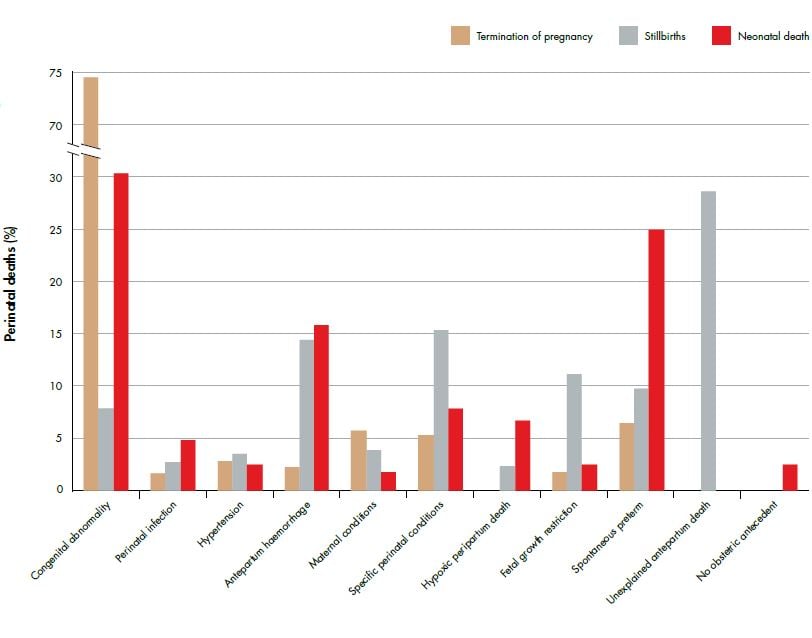

NZ data are consistent with international data and show that the leading cause of perinatal death is congenital abnormality (see Figure 1).2 This is followed closely by spontaneous preterm birth (accounting for 25 per cent of all neonatal deaths) and unexplained stillbirth (accounting for 28 per cent of all stillbirths). Two further primary causes are antepartum haemorrhage (15 per cent of all stillbirths and neonatal deaths) and fetal growth restriction (12 per cent of all stillbirths).

Figure 1. Relative distribution of fetal and neonatal deaths by perinatal death classification (PSANZ-PDC) 2011. Ref 2

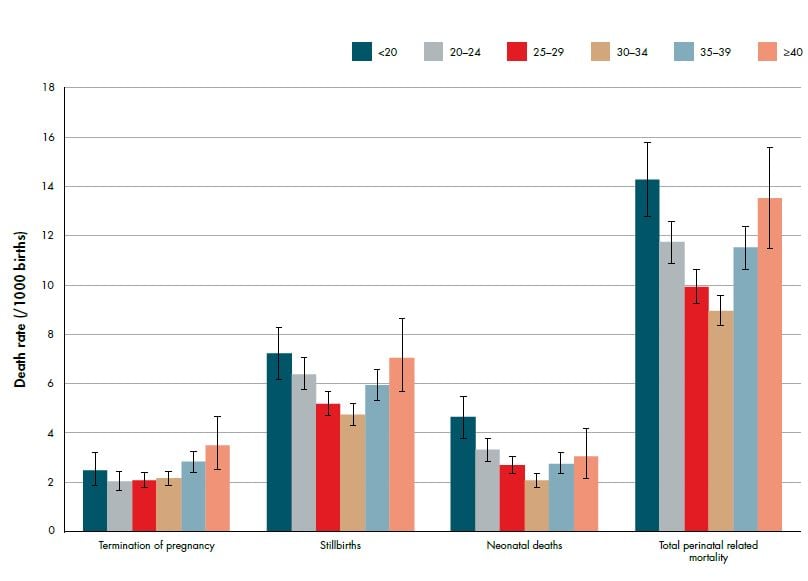

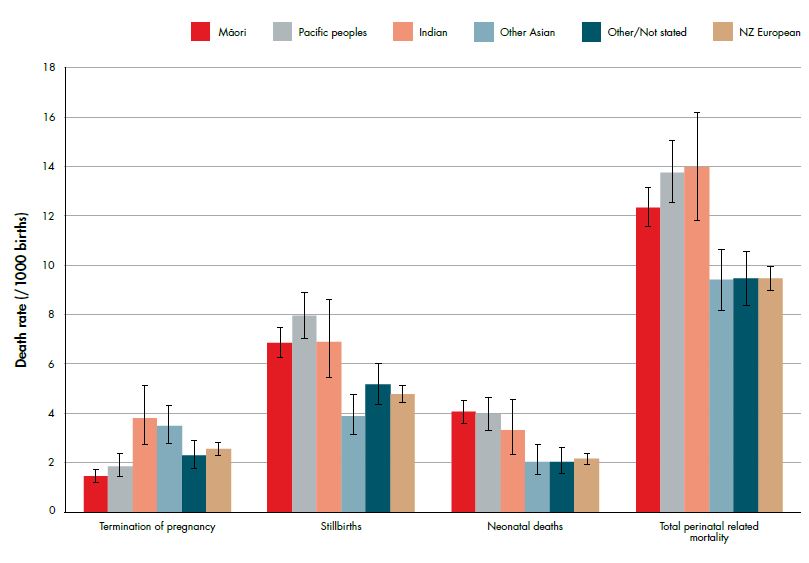

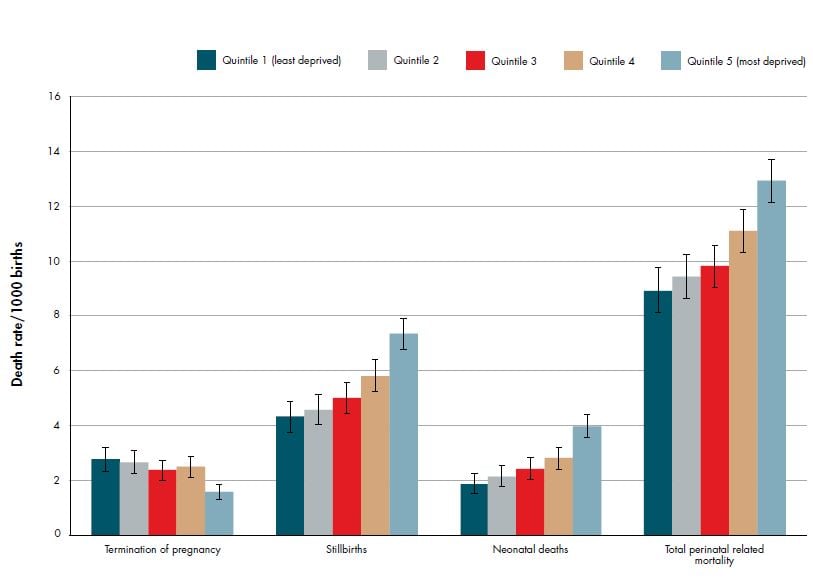

Perinatal death has strong demographic associations with extremes of maternal age (see Figure 2), Maori, Pacific and Indian ethnicity (see Figure 3) and low socioeconomic status (see Figure 4). Additionally, half of perinatal deaths occur among overweight and obese mothers (a quarter occur in women who are obese, BMI ≥30). Smoking and vaginal bleeding in pregnancy are each overrepresented among perinatal deaths (33 per cent and 31 per cent, respectively), against a background rate where approximately 15 per cent of all pregnant women smoke (although this varies substantially by ethnicity) and five per cent experience an antepartum haemorrhage (vaginal bleeding >20 weeks of pregnancy) during pregnancy.2,3 Importantly, obesity, ethnicity, smoking and low socioeconomic status are strongly interrelated. NZ research suggests, in late stillbirth, obesity remains a significant risk factor even after accounting for other socio-demographic factors including ethnicity and socioeconomic status.4

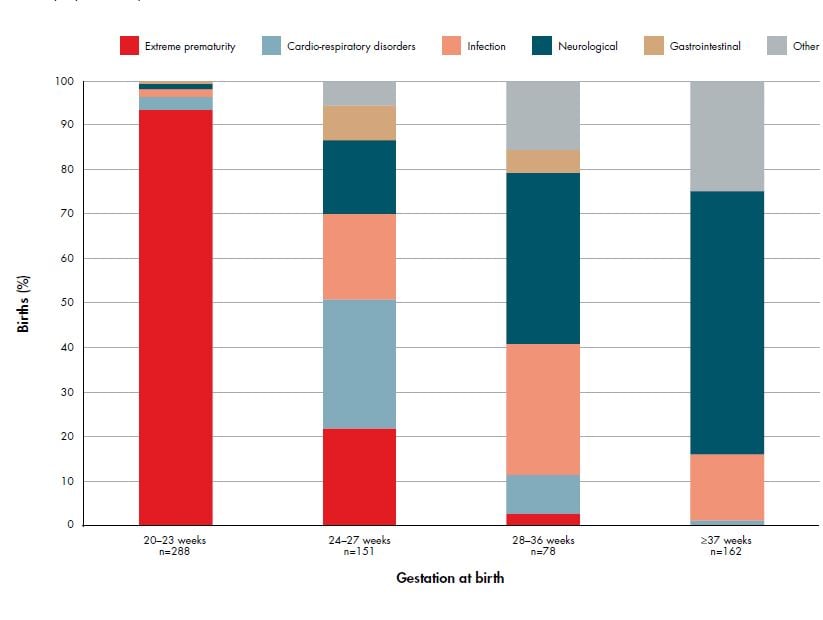

Figure 2. Distribution of neonatal death classification (PSANZ-NDC) among neonatal deaths without lethal congenital abnormality by gestational age group 2007–11. Ref 2

Figure 3. Perinatal related death rates (per 1000 births) by maternal age (with 95 per cent CIs) 2007–11. Ref 2

Unfortunately, over a quarter of all stillbirths are still classified as unexplained.2 This high rate can be partly explained by the low uptake of postmortem examinations; despite being offered to 90 per cent of families who experience a perinatal death, only 37 per cent agree to a postmortem and in approximately ten per cent of cases postmortem is not offered. The PMMRC have assessed postmortem usefulness and found that information gained from this investigation changed the clinical diagnosis and subsequent parental counselling in 24 per cent of assessed cases, highlighting the importance of postmortem in perinatal death assessment.

Excluding congenital abnormality, the most common antecedent in neonatal deaths is preterm birth: 46 per cent of all neonatal deaths occur among babies born <24 weeks gestation and 69 per cent among babies born at <28 weeks gestation (see Figure 2). Importantly, the highest rate of perinatal death due to preterm birth has been observed among women <20 years of age, highlighting again the high-risk nature of teenage pregnancies. Ongoing research into the aetiology and prevention of preterm birth is complex, but has the potential to substantially reduce perinatal mortality rates.

The association between young maternal age and perinatal death is likely confounded by high teenage smoking rates, where smoking is consistently associated with fetal growth restriction, preterm birth, placental abruption and perinatal death. 2,5,6 Additionally, smoking rates vary substantially by ethnicity: one-third of Maori women smoke during pregnancy compared with ten per cent of NZ European and one per cent of Asian women.7 Smoking is one of the few modifiable risk factors for perinatal death.

Figure 4. Perinatal related death rates (per 1000 births) by maternal ethnicity (prioritised) (with 95 per cent CIs) 2007–11. Ref 2

Figure 5. Perinatal related death rates (per 1000 births) by deprivation quintile (NZDep2006) (with 95 per cent CIs) 2007–2011. Ref 2

Antepartum haemorrhage is the primary attributed cause of 15 per cent of neonatal deaths and stillbirths, but is reported in a quarter of stillbirths and over a third of neonatal deaths. When there has been vaginal bleeding after 20 weeks gestation, there is also an increased risk of both fetal growth restriction3 and preterm labour.8 These pregnancies should be considered high risk and monitored closely for signs of preterm labour as well as fetal growth and wellbeing.

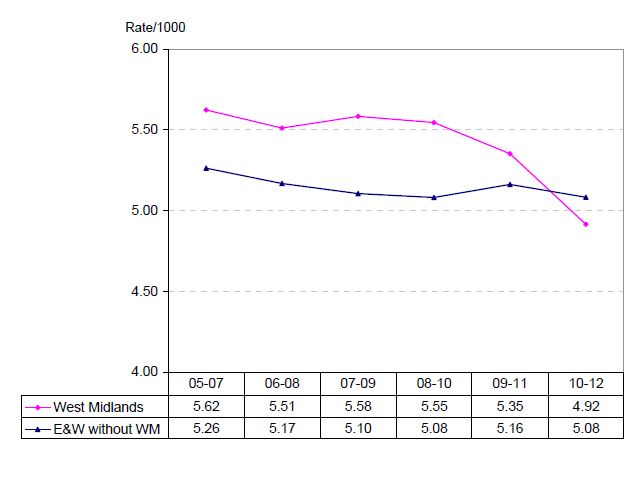

An area where intervention has the potential to change stillbirth rates is antenatal identification of growth-restricted fetuses. In infants without congenital abnormalities, 40 per cent of singleton stillborn infants born after 24 weeks gestation are small for gestational age (SGA) defined as a birthweight <10th customised birthweight centile. However, less than a quarter of these SGA stillborn infants are identified antenatally. Antenatal detection and timely management and delivery of SGA fetuses has been shown to reduce perinatal morbidity and mortality.9 Recent NZ Maternal Fetal Medicine guidelines on the management of suspected SGA have recommended the use of customised antenatal growth charts to aid in antenatal detection of SGA pregnancies.10 Customised birthweight centiles that account for maternal characteristics (such as height, weight and ethnicity) have been shown to better identify babies that are at increased risk of perinatal morbidity and mortality compared with standard population birthweight charts.11,12 The implementation of antenatal customised growth charts in Adelaide, South Australia, led to a 50 per cent increase in antenatal detection of SGA pregnancies among low-risk nulliparous women (from 25 per cent to 50 per cent).13 Recent data from the UK have shown in the regions with widespread use of antenatal customised growth charts, there has been an increase in antenatal detection of SGA infants from 28 per cent to 33 per cent and there has been a significant reduction in SGA stillbirths.14 This trend has not been observed in areas that do not routinely use customised antenatal growth charts (see Figure 6). These observational data suggest that use of customised antenatal growth charts may be of benefit, but data from randomised controlled trials are required to confirm this.

Figure 6. Stillbirths in the West Midlands and the rest of England and Wales. Program of routine antenatal customised growth surveillance implemented in 2009 (3yma = three year moving average). Ref 14

Reasons for the association between obesity and stillbirth are unclear. It has been observed that obesity has an association with SGA as well as LGA infants when using customised birthweight centiles.3,15,16 This is a clinical challenge as SGA is more difficult to detect among obese women.17 Other associations suggested for higher stillbirth rates among obese women include possible reduced perception of fetal movements. Maternal perception of reduced fetal movements in late pregnancy is associated with an increased risk of stillbirth and obese mothers may be less able to assess movements due to increased abdominal girth.18

Maternal sleep practices have also been investigated as a possible risk factor for stillbirth. An Auckland case-control stillbirth study that was the first to investigate maternal sleep position showed women who went to sleep in a non-left lateral position had a 2.3-fold increase in risk of late stillbirth.19 The pathophysiology of this finding may involve compression of the great vessels of the abdomen by the gravid uterus, especially in the supine position. Multicentre studies are currently in progress in NZ and the UK to confirm or refute these findings. If confirmed, a public health message promoting going to sleep in the left lateral position has the potential to reduce late stillbirth rates.

Perinatal death is a tragic and all-too-common complication of pregnancy. In NZ, there are some strong socio-demographic associations whereby women at higher risk of perinatal death can be identified. We will never be able to completely eliminate this devastating event, but we can continue to strive towards reducing perinatal death in our populations by better understanding modifiable risk factors.

References

- Perinatal and Maternal Mortality Review Committee. First Report to the Minister of Health: June 2005 to June 2007. Wellington: Perinatal and Maternal Mortality Review Committee, 2007.

- Perinatal and Maternal Mortality Review Committee. Seventh Annual Report of the Perinatal and Maternal Mortality Review Committee: Reporting mortality 2011. Wellington: Health Quality & Safety Commission, 2013.

- Anderson NH, Sadler LC, Stewart AW, Fyfe EM, McCowan LM. Independent risk factors for infants who are small for gestational age by customised birthweight centiles in a multi-ethnic New Zealand population. ANZJOG 2013;53(2):136-42.

- Stacey T, Thompson JM, Mitchell EA, Ekeroma AJ, Zuccollo JM, McCowan LM. Relationship between obesity, ethnicity and risk of late stillbirth: a case control study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2011;11:3.

- McCowan LME, Dekker GA, Chan E, Stewart AW, Chappell LC, Hunter M, et al. Spontaneous preterm birth and small for gestational age infants in women who stop smoking early in pregnancy: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2009;338:b1081.

- McCowan LME, George-Haddad M, Stacey T, Thompson JMD. Fetal growth restriction and other risk factors for stillbirth in a New Zealand setting. ANZJOG 2007;47(6):450-6.

- Dixon L, Aimer P, Guilliland K, Hendry C, Fletcher L. Smoke Free Outcomes with Midwife Lead Maternity Carers: An analysis of smoking during pregnancy from the New Zealand College of Midwives Midwifery database 2004-2007. New Zealand College of Midwives Journal. 2009 (40):13-9.

- McCormack RA, Doherty DA, Magann EF, Hutchinson M, Newnham JP. Antepartum bleeding of unknown origin in the second half of pregnancy and pregnancy outcomes. BJOG. 2008;115(11):1451-7.

- Lindqvist PG, Molin J. Does antenatal identification of small-for-gestational age fetuses significantly improve their outcome? Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2005;25(3):258-64.

- New Zealand Maternal Fetal Medicine Network. Guideline for the management of suspected small for gestational age singleton pregnancies after 34 weeks’ gestation. Auckland: NZMFMN, 2013.

- McCowan LME, Harding JE, Stewart AW. Customised birthweight centiles predict SGA pregnancies with perinatal morbidity. BJOG. 2005;112(8):1026-33.

- Gardosi J. Clinical strategies for improving the detection of fetal growth restriction. Clin Perinatol. 2011;38(1):21-31, v.

- Roex A, Nikpoor P, van Eerd E, Hodyl N, Dekker G. Serial plotting on customised fundal height charts results in doubling of the antenatal detection of small for gestational age fetuses in nulliparous women. ANZJOG 2012;52(1):78-82.

- Perinatal Institute. Preliminary analysis of Office of National Statistics perinatal mortality rates to 2012. Perinatal Institute; 2013.

- Gardosi J, Clausson B, Francis A. The value of customised centiles in assessing perinatal mortality risk associated with parity and maternal size. BJOG. 2009;116(10):1356-63.

- McIntyre HD, Gibbons KS, Flenady VJ, Callaway LK. Overweight and obesity in Australian mothers: epidemic or endemic? Med J Aust. 2012 20;196(3):184-8.

- Williams M, Southam M, Gardosi J. Antenatal detection of fetal growth restriction and stillbirth risk in mothers with high and low body mass index. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2010 2010;95:Fa92.

- Stacey T, Thompson JM, Mitchell EA, Ekeroma A, Zuccollo J, McCowan LM. Maternal perception of fetal activity and late stillbirth risk: findings from the Auckland Stillbirth Study. Birth. 2011;38(4):311-6.

- Stacey T, Thompson JM, Mitchell EA, Ekeroma AJ, Zuccollo JM, McCowan LM. Association between maternal sleep practices and risk of late stillbirth: a case-control study. BMJ. 2011;342:d3403.

Leave a Reply