Applying educational theory in practical obstetrics and gynaecology settings.

Educating others is a central role of the clinician, in fact, the Hippocratic oath places teaching above all other duties of a doctor.1 It’s hard to imagine another specialty where the scope of teaching and learning is as varied or indeed as challenging as in obstetrics and gynaecology. Without teaching, being an obstetrician and gynaecologist would just become another job.

The Medical Council of New Zealand and Medical Board of Australia emphasise within their Good Medical Practice documents, the importance of teaching and passing on knowledge as a professional responsibility. They state that the teaching should demonstrate the attitudes, awareness, knowledge, skills and practices of a competent and effective teacher.2,3 Likewise, RANZCOG recognises that the ability to teach well is fundamental to the practice of O and G. The College expects its Trainees to develop teaching skills as a common professional objective, participating in hands-on teaching of peers and presenting at in-hospital education sessions. Trainees are required to list these presentations in their Training Record, which is checked by their Training Supervisor on a regular basis. The College expects its specialists to understand and apply the principles of apprenticeship learning for Trainees, students and other health professionals. Teaching attitudes and abilities are assessed through regular formative and summative appraisals.4,5

However, how many times have we, in our role as teachers, felt out of our depth when confronted with the prospect of planning and delivering teaching, let alone knowing whether it has been effective at facilitating learning?

Fortunately, there is a body of educational theory from which we can derive principles to help guide effective teaching. This article aims to describe these central educational theories and demonstrate how they can be applied in three case studies relating to the obstetrician and gynaecologist teaching in the real world.

Adult learning

Malcolm Knowles (1913–97) is famous for popularising the concept of andragogy, described as ‘the art and science of helping adults learn’.6 Andragogy is based on five crucial assumptions about adult learners that differ from the assumptions about child learning.7 The assumptions are summarised as follows:8

- adults are independent and self-directing;

- they have accumulated a great deal of experience, which is a rich resource for learning;

- they value learning that integrates with the demands of their everyday life;

- they are more interested in immediate, problem-centred approaches than in subject-centred ones; and

- they are more motivated to learn by internal drives than by external ones.

Knowles later derived seven principles of andragogy that can be summarised as follows:8

- Establish an effective learning climate, where learners feel safe and comfortable expressing themselves.

- Involve learners in mutual planning of relevant methods and curricular content

- Involve learners in diagnosing their own needs – this will help to trigger internal motivation.

- Encourage learners to formulate their own learning objectives – this gives them more control of their learning.

- Encourage learners to identify resources and devise strategies for using the resources to achieve their objectives.

- Support learners in carrying out their learning plans.

- Involve learners in evaluating their own learning – this can develop their skills of critical reflection.

Case 1. Teaching medical students about subfertility

You have been asked to give a tutorial to a group of fifth-year medical students on their O and G placement on subfertility. It is to take place in a tutorial room off the gynaecology ward. You are told this is the only teaching they will receive on subfertility throughout their undergraduate training. You wonder how you can make the topic understandable to the class in a 60-minute tutorial.

Solution

You could assign the students to small groups of four to six and ask each group to discuss the possible causes of subfertility and ask them to think of ways of classifying these causes into groups (principles 1 and 3). Provide each group with a large piece of paper and a marker pen, and ask them to annotate a diagram of the female and male reproductive tract with different causes of subfertility. Then bring the class together as a whole and ask each group to present their ideas to the class, while you keep a single record on the white board. This will tease out the gaps in the students’ knowledge and engage the whole class in discussion. You could follow this with a brief interactive lecture and provide a handout covering the key points and a couple of short answer questions (principle 1). As a group, work through clinical examples of couples in clinic presenting with subfertility, encouraging participation by all members of the class (principle 2). Return to the short answer questions and ask students to discuss their ideas with their neighbour. A show of hands can be used to establish the class responses and then give the correct answers (principles 1, 2 and 5). Finally, opportunities to attend fertility clinic could be given to put learning into context (principles 6 and 7).

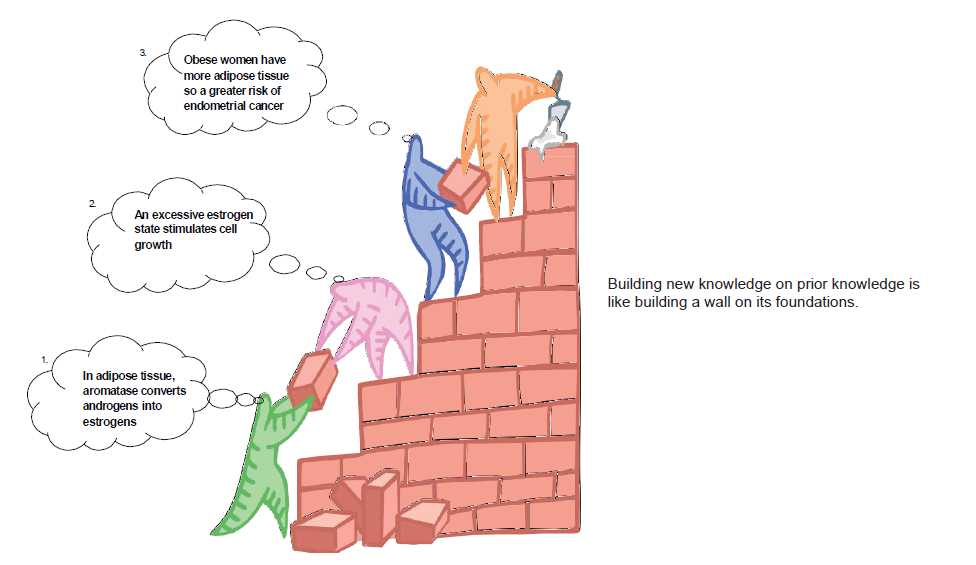

Figure 1. Constructivism in action in an O and G learning environment. Reproduced with permission.15

Knowles himself sums up his work on the topic as ‘people learn best when treated as human beings and the ultimate purpose of all of education is to empower individuals through a process of lifelonglearning.’9 Despite the widespread adoption of andragogy throughout adult education, it is important to recognise that it has been criticised for not being an educational theory, but rather an educational ideology that can lack universal applicability as demonstrated by variations in self-directedness and learner autonomy within differing classes, cultures and levels of maturity.10

An example of an opportunity to utilise andragogy principles in O and G teaching is at a department’s cardiotocography (CTG) meeting. All grades of O and G doctors and midwives are invited to attend a weekly CTG review meeting. The meeting should be advertised as a learning opportunity for all and members of staff should be encouraged to submit cases for presentation and discussion in a non-judgemental environment. Encourage an atmosphere where meeting attendees are able to voice their clinical opinions on the CTG and ask them to back up their thinking by pointing out the various findings on the trace. Discuss management of the case as a group and identify learning objectives from the points raised. Cases should always be provided by the staff members, thus encouraging learners to identify their own learning needs and control their education.

Constructivism

Constructivism views learning as an active, rather than a passive, process. The teacher, instead of merely imparting knowledge, is a guide who facilitates learning.11 The teacher helps the student to activate their existing knowledge, or ‘schema’ on a topic and expose inconsistencies between their current understanding and their new experiences.8 This allows the student to remodel their schema to form a more sophisticated understanding of the subject. This ‘remodelling’ is often most effective when it takes place in the environment or context where the learnt information will be used, for example, learning about obstetric emergencies on the delivery suite. Finally, adequate time must be provided for reflection on the new experience in order to construct understanding.8 An example of constructivism in practice is outlined in Figure 1.

Case 2. O and G RMO/SHO

You are the senior O and G registrar in antenatal clinic with a junior O and G doctor in her first year of specialist training. The clinic is so busy, you have little time to spend with her, besides briefly answering her questions between patients. You wonder how you can provide a valuable learning experience for your Trainee in such a busy working environment.

Solution

You could initially ask if your Trainee would like to sit in on your consultations to watch how you conduct them. Be sure to reflect on your decision-making with her at the end of each consultation and ‘unpack’ your thinking. Why did you make that clinical decision? What was your clinical reasoning (principles 2, 6 and 7)? With your help, she could establish learning objectives based on her perceived areas of weakness (principles 1 and 4). Get your Trainee to see patients independently while keeping a record of challenging clinical problems – ‘reflection on action’ (principles 2 and 6). Encourage her to address these problems by undertaking some self-directed learning and then following up with a case-based discussion with you (principle 5). Finally, observe some of her consultations and provide feedback (principle 5).

Reflective practice

Donald Schön was perhaps the most influential thinker in developing the theory and practice of reflective learning among professionals in the 20th century. His work challenged practitioners, particularly focusing on health professionals, teachers and architects, to reconsider the role of technical knowledge versus artistry in developing professional excellence.12 This artistry, Schön argues, is derived from practitioners reflecting on their actions when unexpected events arise both at the time of the incident and following the incident. The initial reflection, reflection in action, is the ability to learn and develop continually by applying previous experience and knowledge to the unfamiliar event as it is occurring. The reflection that occurs following the event, reflection on action, involves the practitioner analysing the decisions they made, and critically appraising whether their actions were appropriate and how this situation may affect their future practice.8 Reflective learning can be aided with activities such as debriefing with peers or learners, seeking feedback from learners on a regular basis and keeping a journal.8

A common example of reflection in action would be when an O and G Trainee comes across a new situation or problem during a surgical procedure such as caesarean section. The Trainee is forced to reflect on prior experience and their knowledge of the procedure to deal with the new situation in hand. Subsequent reflection on the relative success of their actions during the caesarean then impacts on whether they would employ the same technique if they encountered that problem again (reflection on action).

Self-efficacy

Self efficacy is a central concept of Albert Bandura’s social cognitive theory and describes the idea that a learner’s judgement of their personal ability to deal with a different or novel situation, affects their actions.13,14 These actions include how much effort a learner invests in the given task or situation, how long they persist in the face of adversity and whether they approach the task with trepidation or assuredly.8 Bandura identifies four factors affecting self-efficacy, as follows:13

- Performance attainments. The experience of ‘mastery’ of a task is the most important factor in determining a person’s self-efficacy. Failure of a task lowers self-efficacy, especially if it occurs early in the learning process and is not owing to lack of effort or adverse situations.

- Modelling, or observation of other people. Observing other people similar to us succeeding at a task increases our selfefficacy selfefficacy, whereas watching people failing decreases our selfefficacy.

- Verbal persuasion. Direct verbal encouragement from a credibl source can help increase our self-efficacy, particularly if the task in question is realistic.

- Physiological factors. The physiological symptoms experienced when confronted with stressful situations such as butterflies in the stomach before public speaking, will be interpreted by some as an ominous sign of inability, thus decreasing their self-efficacy. It is a challenge for both teachers and learners to re-interpret their anxiety as excitement or anticipation.

An example of self-efficacy education theory in practice can be demonstrated with the junior O and G Trainee learning to perform a ventouse delivery. The self-efficacy of the Trainee can be elevated by having observed peers, such as the registrar, perform successful ventouse deliveries. That registrar could then offer to observe the Trainee perform ventouse deliveries. Experiencing a successful ventouse delivery is likely to increase the Trainee’s feeling of mastery of the skill and therefore offering the Trainee appropriate ventouse deliveries that are likely to be easier and result in a successful delivery is pertinent. The registrar should provide reassurance that feeling nervous beforehand is a normal experience and is a sign of anticipation. Regular verbal feedback, direction and encouragement should be provided throughout the various steps of the delivery.

Deriving principles from educational theory

With these educational theories in mind, principles can be derived that can be used as tools to help guide the obstetrician and gynaecologist in teaching situations. Kaufman has set out seven principles as follows:8

- The learner should be an active contributor to the educational process.

- Learning should closely relate to understanding and solving reallife problems.

- Learners’ current knowledge and experience are critical in new learning situations and need to be taken into account.

- Learners should be given opportunities and support to use selfdirection in their learning.

- Learners should be given opportunities and support for practice, accompanied by self-assessment and constructive feedback from teachers and peers.

- Learners should be given opportunities to reflect on their practice; this involves analysing and assessing their own performance and developing new perspectives and options.

- The use of role models by medical educators has a major impact on learners. As people often teach the way they were taught, medical educators should model these educational principles with their students and junior doctors. This will help the next generation of teachers and learners to become more effective and should lead to better care for patients.

Case 3. Teaching a new skill

You are the consultant to an O and G registrar who is keen to learn to ultrasound scan. You wonder how to go about teaching him this new skill.

Solution

You could take some time to ask your registrar what aspects of scanning he hopes to learn, where his perceived weaknesses lie and what his time-scale is (principles 1, 2, 3 and 4). Together, draw up a plan of how to tackle these learning objectives and set aside time to meet to discuss progress. You might initially recommend he undertakes some reading on the basic physics and principles behind scanning and assess his understanding by asking some questions to gauge his understanding (principles 4 and 6). Set aside dedicated time together to teach the skill of scanning; arranging to scan appropriate patients who consent to an ultrasound scan as a teaching opportunity, is an excellent way to make the teaching relevant and useful (principles 1 and 2). Be sure to reflect on your techniques and verbalise your actions as well as giving appropriate feedback on your registrar’s progress (principles 5, 6 and 7). Encourage him to take every opportunity to scan patients independently and ask him to keep a journal of his personal learning issues, which he could conduct self-directed learning on or discuss with you (principles 4 and 5).

How to apply these teaching principles

In real life, it is rare for a single teaching principle to be used on its own, therefore the solutions to various teaching problems encountered in everyday practice should include a combination of principles.

Conclusions

Teaching others is a vital role of the obstetrician and gynaecologist and adds to the variety and satisfaction of the specialty. Therefore, we should utilise the educational principles derived from the best evidence and wisdom of educational theory to become more effective teachers and improve the learning experience of our juniors. With time, the use of effecting teaching and learning strategies should result in better trained doctors, who themselves become better educators for the next generation of obstetricians and gynaecologists.

As the well-known Chinese proverb has it: tell me and I forget; show me and I remember; involve me and I understand.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Prof Cindy Farquhar and A/Prof Helen Roberts for their comments on this article.

References

-

- Sokol D. A guide to the Hippocratic Oath.http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/7654432.stm (assessed 7th January 2014).

- Medical Council of New Zealand. Good Medical Practice: a guide for doctors.Chapter 1 in St George IM (ed.). Cole’s medical practice in New Zealand, 12th edition. Medical Council of New Zealand, Wellington.

- Medical Board of Australia. Good Medical Practice: A code ofconduct for Doctors in Australia 2010. Medical Board of Australia, Melbourne.

- The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Curriculum: A framework to guide the training and practice of specialist Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. 2013. The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, Melbourne.

- The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Training Program Handbook 2014. The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, Melbourne.

- Knowles MS, Holton EF, Swanson RA. The Adult Learner: The Definitive

Classic in Adult Education and Human Resource Development (6th ed.).Burlington, MA: Elsevier, 2005. - Smith MK. ‘Andragogy’, the encyclopaedia of informal education.

http://infed.org/mobi/andragogy-what-is-it-and-does-it-help-thinkingabout-adult-learning/ (accessed 4th January 2014). - Kaufman DM. ABC of learning and teaching in medicine: Applying educational theory in practice. BMJ. 2003;326: 213-216.

- Knowles MS & Associates. Andragogy in Action: Applying Modern Principles of Adult Learning. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1984.

- Swanwick T. Informal learning in postgraduate medical education: from cognitivism to ‘culturism’. Med Educ. 2005;39(8): 859-865.

- Biggs J, Tang C. Teaching for Quality Learning at University. 4th Edition. Buckingham: SRHE; 2011.

- Schön DA. Educating the reflective practitioner: toward a new design for teaching and learning in the professions. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.1987.

- Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: a social cognitive

theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1986. - Kaufman DM, Mann KV. Teaching and learning in medical education: how theory can inform practice. In: Swanwick T. Understanding Medical Education: Evidence, Theory and Practice. Hoboken, NJ USA: Wiley-

Blackwell, 2010. - Shehmar M, Khan KS. A guide to the ATSM in Medical Education.Article 1: Principles of Teaching and Learning. The Obstetrician and Gynaecologist. 2009; 11:271-276.

Leave a Reply