Lessons learned from using the Essure hysteroscopic sterilisation method in Auckland Hospital since 2010.

I became interested in the Essure® method as I work in diabetes antenatal clinic. Many women with diabetes are poor candidates for a laparoscopic sterilisation in view of their high BMI. We initially started with the procedure in a day-surgery setting, but moved it to our outpatient clinic a year ago. I have performed around 200 procedures, most of them without any anaesthetic. The patients had an average BMI of 30 with a maximum BMI of 60. The average ‘scope time’ (time from scope in to scope out) is five minutes. Overall, we have had excellent results with this method of sterilisation and find it works well for our population.

The method

In November 2002, Essure Permanent Birth Control System (Conceptus Inc, San Carlos, CA) became the first method of transcervical sterilisation approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use in the USA. It has been performed more than 650 000 times worldwide since.

The Essure device is a metal and polymer micro-insert 4cm long and 1–2mm wide when deployed. It consists of an inner coil of stainless steel and polyethylene terephthalate (PET) fibres and an outer coil of nickel-titanium (nitinol). It comes loaded in a single-use delivery system.

The device is placed in the proximal fallopian tube under hysteroscopic guidance. The coil initially is in a tightly wound state and then is deployed to an expanded state that anchors the insert in the tube. After placement, the PET fibres stimulate benign tissue growth, which surrounds and infiltrates the device over the course of several weeks, leading to tubal occlusion.1

Either an ultrasound scan or a hysterosalpingogram is performed 12 weeks later to confirm correct placement of the Essure devices.2 Contraception must be used until satisfactory micro-insert location and bilateral tubal occlusion are confirmed.

Adiana, another hysteroscopic sterilisation device, was introduced in 2009, but taken off the market in 2012 by the manufacturer for business reasons.

Complications:

- Infection – the risk is similar to other hysteroscopic procedures, which is around 0.1–0.9 per cent.4

- Perforation – tubal or uterine perforation has been reported in one-to-three per cent of cases.5 The perforation might be suspected at the time of the procedure owing to increased pain or unusual distal movement of the device intra-operatively. As the perforation can be asymptomatic it can also be picked up at the time of the follow-up test. A micro-insert that is protruding into or is free in the peritoneal cavity may need to be removed. The concern is significant adhesion formation resulting from the PET fibres.

- Expulsion – this occurs in less than one per cent of cases.6 Most expulsions present in the first three months and are therefore picked up at the follow-up test. The expulsion can be either through the cervix or from the distal end of the Fallopian tube.

- Failure to prevent pregnancy – the occurrence is from 0.16–0.25 per cent. The risk of falling pregnant is similar to or better than other contraceptive methods. In a large study of 50 000 procedures, 64 patients fell pregnant. All of these cases involved protocol deviations.7 Failures seem to be associated with pregnancy at time of placement, incorrect placement (perforation), non-compliance with follow-up instructions and misreading of imaging studies.

- Chronic pain – there are reports of chronic pelvic pain requiring removal of the devices, usually by laparoscopy.8

Patient satisfaction

A study by Duffy et al compared laparoscopic tubal ligation (Filshie clip) with Essure hysteroscopic sterilisation.9 The results showed 82 per cent of Essure patients reported procedure tolerance as ‘excellent to good’ compared with 41 per cent of patients who underwent laparoscopic tubal ligation. This study also evaluated patient satisfaction after a 90-day interval. Of the Essure patients, 100 per cent were satisfied with their recovery, compared with 80 per cent of the laparoscopic tubal ligation patients.

Advantages and disadvantages:

- no incisions;

- no need for general anaesthetic;

- less postoperative pain;

- faster postoperative recovery;

- need for follow-up imaging after three months; and

- need for continued use of contraception until satisfactory

follow-up test.

Contraindications:

- uncertainty about non-reversible sterilisation;

- pregnancy or suspected pregnancy;

- less than three months from pregnancy (including TOP/ miscarriage);

- active or recent pelvic infection;

- known allergy to contrast media (unable to undergo HSG for confirmation test); and

- hypersensitivity reaction to nickel (however, in 2011, the FDA removed hypersensitivity reaction to nickel as a contraindication to the procedure as the number of adverse events reported had been extremely low (less than 1:5000).12

Post-procedure restrictions:

MRI is safe. Pelvic use of unipolar electrosurgery is contraindicated. The FDA has approved endometrial ablation using bipolar radiofrequency, a hot liquid filled balloon or circulating hot water (hydrothermal), as long as there is no reasonable concern that uterine perforation occurred during the sterilisation procedure.13

A 2010 publication by Levie et al specifically addressed the question of patient satisfaction with office-based Essure sterilisation.10 The majority of these patients (70 per cent) rated procedure-associated pain as equal to or less than their typical menstrual pain. Their follow-up surveys were very positive in regard to patient satisfaction. Follow-up surveys were collected for 84 per cent of the study patients and, of these, 92 per cent preferred having the procedure done in the office, 98 per cent would recommend the procedure to a friend, and 93 per cent would undergo the procedure again if necessary. It is not surprising that higher satisfaction was significantly correlated with lower average pain scores.

How is the procedure done?

Timing of procedure and endometrial preparation

To achieve high successful placement rates it is essential to optimise the view of the ostia. The best views are obtained when the endometrium is thin. Ideally the procedure should be performed between days five and ten of the menstrual cycle; this also avoids early luteal phase pregnancies. In practice, we have found it works best to manipulate the period so that the procedure can be booked well in advance. We usually achieve this by either causing a withdrawal bleed after stopping the combined oral contraceptive pill or causing a withdrawal bleed after a five-day course of once-a-day 10mg oral medroxyprogesterone (Provera). Alternatively, we use the progesterone-only pill for a at least a month. If the patient is amenorrhoeic postpartum, or has established use of Depo Provera or a progesterone implant, the procedure can be scheduled at any time.

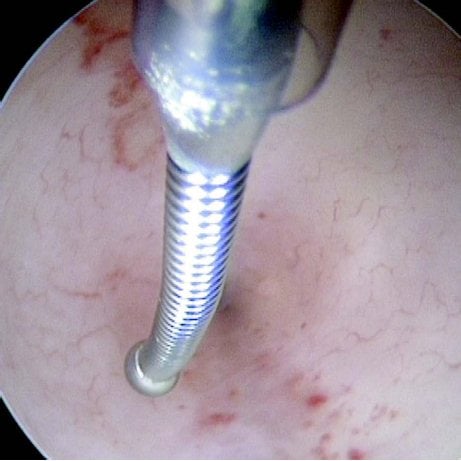

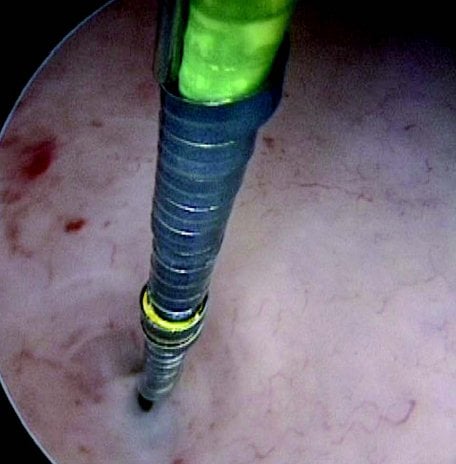

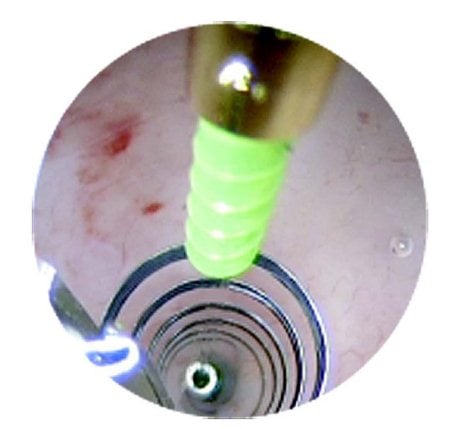

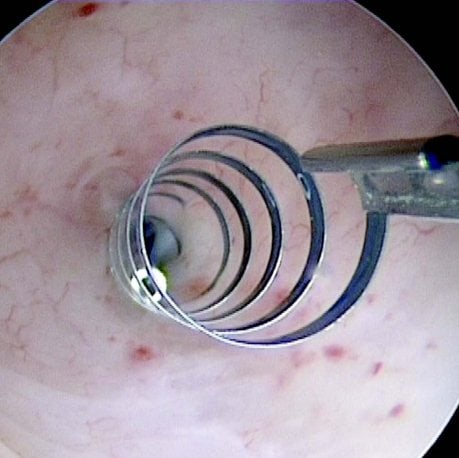

Figures 1–8. Facing page top left, bottom left; top right, bottom right; this page top left, bottom left; top right, bottom right. Placement of the Essure device via the Bettochi hysterscopy approach.

Pre-operative

Pre-medication with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs has been recommended to reduce tubal spasm. We use Voltaren SR 75mg an hour before the procedure.

Outpatient clinic set-up

Equipment required:

- Essure devices (good to have spare ones in case of technical difficulties);

- rigid hysteroscope with 5-French operating channel – approximately 3mm diameter with double current sheath

(external diameter generally 5–5.5mm); - hysteroscopic grasper; and

- warmed up normal saline one-litre bags – use sparingly as increased pressure increases patient discomfort and increases tissue oedema, which can make visualisation of the ostia difficult over time.

Personnel

A three-person team is ideal, including: the surgeon; a sterile assistant helping with insertion of introducer and Essure device in the operating channel; and a circulating nurse who can also attend to the patient’s needs.

Procedure

Bettochi hysteroscopy approach, see Figures 1–8.

Who should perform Essure placement?

In March 2014, a study from Yale was published by Aileen Gariepy comparing probability of pregnancy after hysteroscopic sterilisation and two different types of laparoscopic tubal occlusion.11 In their model, the hysteroscopic sterilisation had a higher failure rate compared to the laparoscopic approaches, however, this was owing to patients not completing all the steps of the procedure. The study highlights the discrepancy between ‘perfect’ and ‘typical’ use. In some cases financial issues, such as the patient’s health insurance not necessarily covering the costs for the follow-up tests, were a factor.

This study supports my belief that the procedure should only be performed by doctors who do the procedure frequently, follow strict protocols, follow up every patient and audit their own results. In Auckland we had only one-to-two per cent of patients failing to return for follow up.

Conclusion

Essure is an effective and safe contraception option for women to consider, especially women with increased BMI. It is important Essure placement occurs in an appropriate setting and is performed by trained personnel.

References

- Valle RF, Carignan CS, Wright TC, STOP Prehysterectomy Investigation Group. Tissue response to the STOP microcoil transcervical permanent contraceptive device: results from a prehysterectomy study. Fertil Steril 2001; 76:974.

- Veersema S1, Vleugels MP, Timmermans A, Brölmann HA. Follow-up of successful bilateral placement of Essure microinserts with ultrasound. Fertil Steril 2005 Dec;84(6):1733-6.

- Povedano B1, Arjona JE, Velasco E, Monserrat JA, Lorente J, Castelo- Branco C. Complications of hysteroscopic Essure® sterilisation: report on 4306 procedures performed in a single centre. BJOG. 2012 Jun;119(7):795-9.

- Agostini A, Cravello L, Shojai R, et al. Postoperative infection and surgical hysteroscopy. Fertil Steril 2002; 77:766.

- Hurskainen R, Hovi SL, Gissler M, et al. Hysteroscopic tubal sterilization: a systematic review of the Essure system. Fertil Steril 2010; 94:16.

- Arjona JE, Miño M, Cordón J, et al. Satisfaction and tolerance with office hysteroscopic tubal sterilization. Fertil Steril 2008; 90:1182.

- Levy B, Levie MD, Childers ME. A summary of reported pregnancies after hysteroscopic sterilization. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2007; 14:271.

- Hur HC, Mansuria SM, Chen BA, Lee TT. Laparoscopic management of hysteroscopic essure sterilization complications: report of 3 cases. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2008; 15:362.

- Duffy S, Marsh F, Rogerson L, et al. Female sterilisation: A cohort controlled comparative study of ESSURE versus laparoscopic sterilisation. BJOG 2005;112(11):1522–1528.

- Levie M, Weiss G, Kaiser B, Daif J, Chudnoff SG. Analysis of pain and satisfaction with office-based hysteroscopic sterilization. Fertil Steril 2010;94(4):1189–1194.

- Gariepy AM, Creinin MD, Smith KJ, Xu X. Probability of pregnancy after sterilization: a comparison of hysteroscopic versus laparoscopic sterilization. Contraception 2014 Apr 24. pii: S0010-7824(14)00143- 7. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2014.03.010. [Epub ahead of print].

- www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/ProductsandMedicalProcedures/DeviceApprovalsandClearances/PMAApprovals/ucm273626.htm .

- www.essuremd.com/Portals/essuremd/PDFs/TopDownloads/CC-3032 per cent2028FEB12F per cent20physician per cent20customer per cent20letter.pdf.

Leave a Reply