Background

Adnexal torsion is a rare cause of acute abdominal pain and diagnosis can be challenging because the presentation is often characterised by non-specific symptoms. It requires a high clinical suspicion for prompt diagnosis in order to save the adnexal organs.

Case report

A 32-year-old primiparous woman presented at 17 weeks with sudden onset of right iliac fossa pain that woke her from sleep. She described the pain as severe and constant, sharp in character, radiating down to her right groin and associated with nausea and vomiting. The patient did not have any vaginal discharge, bleeding or contractions. There was no other medical, surgical or gynaecological history of note. The pregnancy was naturally conceived with a normal antenatal course. Imaging to date had been unremarkable.

On examination, the patient was distressed, but afebrile and haemodynamically stable. She had right lower quadrant tenderness, with a palpable mass. Pelvic ultrasound reported right adnexal 75x42x34mm ovoid heterogeneous mass with no internal vascularity that appeared to be separate from the uterus. Blood flow to the right ovary could not be demonstrated. The fetal examination was normal.

Acute appendicitis was a differential diagnosis, but seemed unlikely. Adnexal torsion, although considered, was not convincing. The patient was admitted for analgesia and observation. On the following day, her abdominal pain remained localised in the right iliac fossa and seemed to improve. Bedside ultrasound was performed by the obstetrics and gynaecology team and suggested a dermoid cyst. With adequate analgesia, the patient remained comfortable and the inflammatory markers remained normal.

Figure 1. Transabdominal pelvic ultrasound: right heterogenous mass with no vascularity on colour Doppler. No evidence of calcification, fat-fluid level, or necrosis and with a texture of haemorrhage. No free fluid. Ovary could not be separately identified from the mass. Courtesy of Gosford Hospital Radiology Department and Dr Rajiv Rattan.

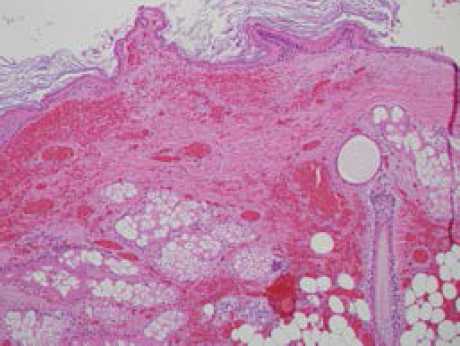

Figure 2. Histology slide. Torted dermoid cyst showing haemorrhage and necrosis, squamous epithelium, sebaceous glands, adipose tissue, hair shaft and area of layers of keratin. [H&E stain]. Image courtesy of Gosford Hospital Pathology and Dr Julienne Grace.

Pre-operative serum tumour markers CA 19-9 and CA 125 returned elevated readings at 497.4 and 70.5, respectively. Of note, spontaneous labour occurred at 40+8 weeks gestation and delivery was by caesarean section for prolonged second stage.

Discussion

Adnexal torsion accounts for about three per cent of gynaecological emergencies and is usually caused by the total or partial rotation of the ovary and the fallopian tube on its vascular pedicle.3 It can occur in all ages, but is more common during the reproductive years4 because of the development of a corpus luteal cyst during the menstrual cycle.3 It is a rare cause of abdominal pain in pregnancy, with an incidence of five per 10 000 pregnancies.5

Key points

- Adnexal torsion should be considered in any presentation of sudden-onset lower abdominal pain and adnexal mass.6

- Diagnosis can be challenging, owing to the relatively nonspecific symptoms and laboratory findings.6

- Imaging modalities may be suggestive, but are not conclusive.

- Prompt diagnosis and management is essential to optimise outcomes.

Factors that predispose to adnexal torsion include tubal congenital or acquired anomalies, such as hydrosalpinx and tubo-ovarian masses.6 It may be associated with stimulation during fertility treatment, most notably IVF.5 An average 50–80 per cent of cases are associated with an ovarian tumour, typically benign, or with a large heavy cyst.3 When it occurs during pregnancy, torsion is common in the second and early third trimester and necrosis may precipitate peritonitis with preterm labour.2,5,6 The commonest presenting symptom is lower quadrant pain, with non-specific symptoms such as nausea, vomiting and fever. The pain is typically sudden in onset and may be constant or paroxysmal, radiating to the thigh or groin.6 Torsion is more common on the right side, presumably owing to the sigmoid colon, which makes adnexal movement less likely on the left.4

No specific laboratory tests are helpful in the evaluation of a patient for suspected adnexal torsion in pregnancy.3 A raised white cell count is a non-specific finding and unreliable indicator of torsion. Imaging usually reveals an enlarged displaced ovary or adnexal mass, sometimes with evidence of haemorrhage and free fluid.3 Doppler flow studies are commonly equivocal3 and the absence of adnexal blood flow has a poor negative predictive value.2

Management of adnexal torsion in pregnancy is controversial owing to the associated risks.5 Laparoscopy during pregnancy has an increased risk of injury to the uterus and possibly pregnancy loss.8 The safest time to perform laparoscopic surgery in pregnancy is usually the second trimester, and surgery prior to the third trimester has the least risk of premature delivery.9 However, it remains unclear whether preterm labour associated with laparoscopic surgery in pregnancy is secondary to the underlying pathology or surgery itself.9

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Dr Julienne Grace who provided the histological examination of the lesion and Dr Rajiv Rattan who provided the pelvic ultrasound examination.

Consent

Written informed consent to publish this case report and images was obtained from the patient.

References

- Origoni M, Cavoretto P, Conti E, Ferrari A. Isolated tubal torsion in pregnancy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol [Internet]. 2009 Oct [cited 2014 Mar 28];146(2):116-20. Available from: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19493607 doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2009.05.002.

- Morton MJ, Masterson M, Hoffman B. Case report: ovarian torsion in pregnancy – diagnosis and management. J Emerg Med [Internet]. 2013 Sep [cited 2014 Mar 27];45(3):348-51. Available from: www.jemjournal.com/article/S0736-4679%2812%2901689-7/ doi:1016/j.emermed.2012.02.089.

- Marx JA, Hockberger RS, Walls RM. Rosen’s emergency medicine: concepts and clinical practice. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2014.

- Ryan MF, Desai BK. Ovarian torsion in a 5-year old: a case report and review. Case Rep Emerg Med [Internet]. 2012 Apr [cited 2014 Mar 26];2012(2012):1-3. Available from:www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3542900/doi:10.1155/2012/679121.

- Ali MK, Abdelbadee AY, Shazly SA, Abbas AM. Case report: adnexal torsion in the first trimester of pregnancy. Middle East Fertil Soc J[Internet]. 2013 May [cited 2014 Mar 28];18(4):284-6. Available from:www.researchgate.net/publication/259521147_Adnexal_torsion_in_the_first_trimester_of_pregnancy_A_case_report .

- Varghese U, Fajardo A, Gomathinayagam T. Isolated fallopian tube torsion with pregnancy- a case report. Oman Med J [Internet]. 2009 Apr [cited 2014 May 03];24(2) :128–30. Available from: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3274695/ doi: 10.5001/omj.2009.27.

- Yalcin OT, Hassa H, Zeytinoglu S, Isiksoy S. Isolated torsion of fallopian tube during pregnancy; report of two cases. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol [Internet]. 1997 Aug [cited 2014 May 07]; 74(2):179-82. Available from: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9306114 .

- Al-Fozan H, Tulandi T. Safety and risks of laparoscopy in pregnancy. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol [Internet]. 2002 Aug [cited 2014 Apr 01];14(4):375-9. Available from: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12151826 .

- Nezhat FR, Tazuke S, Nezhat CH, Seidman DS, Phillips DR, Nezhat CR. Laparoscopy during pregnancy: a literature review. JSLS [Internet]. 1997 Jan-Mar [cited 2014 Apr 01];1(1):17–27. Available from: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3015223/.

- Koçak M, Dilbaz B, Ozturk N, Dede S, Altay M, Dilbaz S, et al. Laparoscopic management of ovarian dermoid cysts: a review of 47 cases. Ann Saudi Med [Internet]. 2004 Sep-Oct [cited 2014 Mar 29];24(5):357-60. Available from: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15573848 .

- Ulkumen BA, Goker A, Pala HG, Ordu S. Abnormal elevated CA 19-9 in the dermoid cyst: a sign of the ovarian torsion? Case Rep Obstet Gynecol [Internet]. 2013 Jun [cited 2014 Mar 28];2013(2013):1-2. Available from: www.hindawi.com/journals/criog/2013/860505/.

- De Santis M, Licameli A, Spagnuolo T, Scambia G. Laparoscopic management of a large, twisted, ovarian dermoid cyst during pregnancy: a case report. J Reprod Med [Internet]. 2013 May-Jun [cited 2014 Apr 06];58(5-6):271-6. Available from: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23763016.

- Mikuni M, Makinoda S, Tanaka T, Okuda T, Domon H, Fujimoto S. Evaluation of tumor marker in ovarian dermoid cyst. Nihon Sanka Fujinka Gakkai Zasshi [Internet]. 1990 May [cited 2014 Mar 30]; 42(5):479-84. Available from: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2373920.

- Var T, Tonguc EA, Ugur M, Altinbas S, Tokmak A. Tumor markers panel and tumor size of ovarian dermoid tumors in reproductive age. Bratisl Lek Listy [Internet]. 2012 [cited 2014 Apr 02];113(2):95-8. Available from: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22394039.

Leave a Reply