Should we excise or ablate all small deposits of endometriosis at laparoscopy?

Endometriosis, characterised by the finding of endometrial-like tissue outside the uterus, is one of the most common gynaecological conditions associated with pain and subfertility among women of reproductive age.1 It is one of the leading indications for laparoscopic surgeries both for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes in women presenting with pain or infertility.2,3

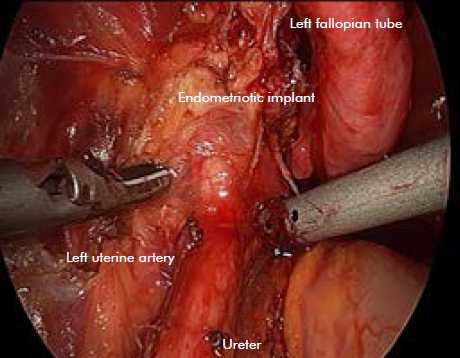

Among the many on-going controversies regarding the management of this enigmatic condition is the question of whether it is worthwhile going to all the trouble of excising small deposits of endometriosis at laparoscopy, or whether cauterising them achieves the same outcomes in terms of pain and fertility (see Figure 1).

Within the limited scope of this article, we will attempt to address this fundamental question by reviewing current knowledge of the mechanisms of pain and infertility in association with endometriosis, considering the differences between excision and ablation in terms of diagnostic and therapeutic merits, and finally appraising the scientific evidence of excision versus ablation in terms of pain and fertility outcomes.

Pain symptoms most commonly associated with endometriosis are dysmenorrhoea, dyspareunia and non-menstrual pelvic pain.4 These symptoms may exist in variable combination and may fluctuate in severity from person to person and from time to time.5 There is good evidence linking pain to endometriosis, with estimated prevalence ranging from 30–90 per cent among women undergoing laparoscopy for evaluation of chronic pelvic pain.6 There is also strong evidence supporting significant pain improvement and surgical treatment of endometriosis.7, 8

However, the relationship between pain and endometriosis is not clear cut as endometriotic lesions similar to those found in women presenting with pain have also been detected in up to 43 per cent of asymptomatic women.9 This observation suggests that the mechanisms by which endometriosis causes pain are still not fully understood and may vary from person to person.10 Pain from endometriosis is thought to arise predominantly through nociceptive, inflammatory and neuropathic pathways as a result of direct effects of cyclical active bleeding from endometriotic implants, and indirect effects involving the production of cytokines and nerve growth factors by endometriotic cells and activated macrophages activating silent nociceptors, irritating and stimulating neuronal ingrowth into nerve endings of pelvic floor nerves especially in the pouch of Douglas and the areas of the uterosacral ligaments.11-13 Another puzzling aspect between endometriosis and pain is the observation that the association between endometriosis stage and severity of pelvic symptoms is marginal and inconsistent.14-16 On the basis of these observations, one can appreciate the difficulty in evaluating pain as an outcome measure following surgical treatment of endometriosis.

How does endometriosis cause subfertility/infertility?

Similar to pain, there is considerable epidemiological evidence linking endometriosis and subfertility. These include higher prevalence of endometriosis from 25–40 per cent in subfertile women compared to 0.5 to five per cent in fertile women17, reduced fecundity from 0.02 to 0.10 in women with untreated endometriosis compared to 0.15 to 0.20 in normal couples18, 19, reduced fecundity after husband sperm insemination in women with minimal to mild endometriosis compared with those with a normal pelvis, reduced fecundity and cumulative pregnancy rate after donor sperm insemination in women with minimal-mild endometriosis compared with those with a normal pelvis20, a negative correlation between the r-AFS stage of endometriosis and the monthly fecundity rate21, reduced implantation rate per embryo after IVF in women with moderate to severe endometriosis compared with women with a normal pelvis, an increased monthly fecundity rate and cumulative pregnancy rate after surgical removal of minimal to mild endometriosis.22 By contrast, others have found no difference in fertility outcome for women with infertility-related endometriosis compared to control and no clear association between the effect of different stages of endometriosis on IVF-ET outcomes.23, 24

Figure 1. A large endometriotic implant being excised over the top of the left ureter.

While there is a strong association between endometriosis and infertility, no causal relationship has been clearly established. The many mechanisms by which endometriosis may cause subfertility include adhesions and distorted pelvic anatomy that prevent oocyte release or transport, increased peritoneal fluid concentration of inflammatory cytokines that may have adverse effects on oocyte function and quality, sperm motility, sperm DNA, sperm capacitation, oocyte-sperm interaction, fallopian function, impaired implantation and abnormalities in embryo quality.25, 26 These conflicting observations highlight the difficulty when measuring fertility as an outcome following medical or surgical interventions, thus accounting for on-going lack of consensus about the choice and consequence of surgical treatment modality.

Factors that influence the choice of surgical method

In general, the aims of laparoscopic surgery of endometriosis are to remove (excise) or destroy (ablate) all visible endometriotic lesions, to divide adhesions and restore normal anatomy, and to repair damage to reproductive organs.27 The choice of techniques for surgical treatment of endometriosis currently includes sharp dissection, electro-surgery, Argon Neutral Plasma Energy, laser or harmonic energy.28

Ideally, the choice of surgical instrumentation (scissor dissection, electrosurgery, laser, harmonic, argon beam) and the mode of treatment surgical technique (excision or ablation) should be made on the basis of understanding of pathophysiology of the disease, the mechanisms of action, the tissue effects of the chosen surgical treatment modality and the outcomes of randomised controlled clinical trials.29 However, most studies to date, including the few randomised controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating surgical treatment of endometriosis, have failed to give detailed technical description, standardised surgical technique or described the energy modality used. Nevertheless, major factors which should be considered in determining whether to excise or ablate include diagnostic benefit, tissue effects, haemostasis and time.

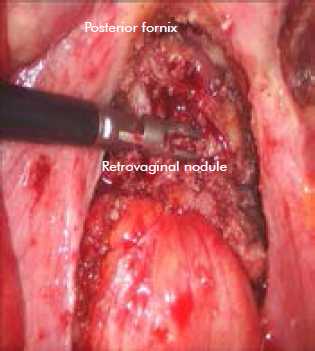

Figure 2. Deep rectovaginal endometriotic nodule infiltrates through posterior fornix – being completely excised.

While laparoscopy is the recognised gold standard for diagnosis of endometriosis, in the absence of histological sampling, the false-positive rate with laparoscopic visualisation alone may approach 50 per cent, especially in women with minimal or mild endometriosis.30 From this point of view, excision has a diagnostic advantage over ablation for histological confirmation.31 The question of whether selective excision of some lesions and ablation of the remaining would suffice both diagnostic and therapeutic outcomes (pain and fertility) has not been addressed.

Furthermore, the choice of instrumentation and the decision to excise or ablate should not only include consideration of speed, efficacy, safety and cost-efficiency, but also haemostasis, tissue tensile strength, extent of tissue injury, rapidity of wound healing (see Figure 2). With the exception of cold scissor excision, other devices (unipolar or bipolar electrosurgery, argon beam, laser, harmonic) all involve heat energy to denature protein, leading to vascular tamponade and haemostasis on the one hand, lateral thermal spread, delayed wound healing and risk of delayed damage to vital adjacent structures such as ureter, bowel, bladder on the other hand.32

When taking the above factors into consideration, the overall theoretical and technical advantages which favour ablation over excision are speed, haemostasis, technical lenience, thus ease of adoption and generalisability, with perhaps equivalent safety but at the expense of incomplete destruction of deep endometriosis and lower diagnostic accuracy.33

Appraisal of scientific evidence

In the recent Cochrane Review into laparoscopic surgery for endometriosis34, the authors identified two RCTs that compared laparoscopic excision with ablation.35,36 Wright and colleagues reported good symptom relief at six months irrespective of the treatment modality for the majority of participants in a study involving 24 women with mild endometriosis presenting with chronic pain.35 While the authors gave details regarding the surgical technique, limitations from this study include inadequate sample size, the use of a ranked ordinal scale, the use of both coagulation and cut current in the excision group. Healey and colleagues also found no significant difference in pain outcomes between the two treatment modalities at 12 months.36 However, at five-year follow-up, the same authors reported a significantly greater reduction in dyspareunia VAS scores in the excision group and a higher use of medical treatments among the ablation group.37 The findings of this well-designed RCT have some limitations including a lack of detailed description of the surgical technique, failure to specify how the endometriotic lesions were excised or ablated and a high drop-out rate at five-year follow-up.38

In terms of fertility outcome, meta-analysis of two RCTs in the 2010 Cochrane Review into laparoscopic surgery for subfertility associated with endometriosis concluded that laparoscopic treatment of minimal and mild endometriosis may improve the on-going pregnancy rate and live birth rate in couples with otherwise unexplained infertility.34 In the Marcoux study, the laparoscopic treatment involved the destruction or removal of all visible endometriotic implants and the lysis of adhesions while the choice of instruments was left to the surgeons.39 In the Group Italiano study that involved seven centres, the only description of the surgical intervention was that adhesiolysis was allowed in women allocated to resection or ablation of visible endometriosis with no details regarding whether all lesions were treated nor the choice of instruments.40 To date, no RCTs have compared whether excision or ablation improves fertility in deep or stage 3 to 4 endometriosis.

Conclusions

The current level of understanding and evidence does not allow us to answer the question of whether we should excise or ablate all small deposits of endometriosis at laparoscopy in terms of pain and fertility. Nevertheless, there are several practical implications which can be drawn from the limited evidence. Firstly, the use of laparoscopic surgery (excision or ablation) has been shown to improve fertility in women with minimal or mild endometriosis, but evidence is lacking in women with more advanced endometriosis. Secondly, excision offers tissue for histological confirmation while visual inspection alone followed by ablation may be associated with a higher risk of false-positive diagnosis. Thirdly, ablation is quicker, easier, less vascular and technically less demanding than excision, but is not necessarily safer than excision. Finally, general consensus recommends excision over ablation for removal of deep endometriotic lesions.41

References

- Giudice L. Endometriosis. New Engl J Med 2010; 362:2389-98.

- Jacobson TZ, Duffy JM, Barlow D, Koninckx PR, Garry R. Laparoscopic surgery for pelvic pain associated with endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009; 4: CD001300.

- Mcleod B, Retzloff M. Epidemiology of Endometriosis: An Assessment of Risk Factors. Clinical Obstet Gynecol 2010; 53 (2): 389-396.

- Guo SW, Wang Y. The prevalence of endometriosis in women with chronic pelvic pain. Gynecol Obstet Invest 2006; 62:121-30.

- Stratton P, Berkley KJ. Chronic pelvic pain and endometriosis: translational evidence of the relationship and implications. Hum Reprod Update 2011; 17:327-346.

- Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Treatment of pelvic pain associated with endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2008;90 (5 Suppl):S260-269.

- Sutton CJ, Ewen SP, Whitelaw N, Haines P. Prospective, randomized, double-blind, controlled trial of laser laparoscopy in the treatment of pelvic pain associated with minimal, mild, and moderate endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 1994;62:696-700.

- Abbott J, Hawe J, Hunter D, Holmes M, Finn P, Garry R. Laparoscopic excision of endometriosis: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Fertil Steril. 2004;82:878-884.

- Moen MH, Stokstad T. A long-term follow-up study of women with asymptomatic endometriosis diagnosed incidentally at sterilization. Fertil Steril. 2002; 78:773-776.

- Howard FM. Endometriosis and mechanisms of pelvic pain. Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology (2009) 16, 540-50.

- Howard FM: The role of laparoscopy in chronic pelvic pain: promise and pitfalls. Obstet Gynecol Surv 1993; 48: 357-387.

- Porpora MG, Koninckx PR, Piazze J, Natili M, Colagrande S, Cosmi EV. Correlation between endometriosis and pelvic pain. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc 1999; 6:429-34.

- Hansen K, Chalpe A, Eyester K. Management of endometriosis associated-pain. Clin Obset Gynecol 2010; 53: 439-448.

- Vercellini P, Trespidi L, De Giorgi O, et al. Endometriosis and pelvic pain: relation to disease stage and localization. Fertil Steril. 1996; 65:299-304.

- Whiteside JL, Falcone T. Endometriosis-related pelvic pain: what is the evidence? Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2003; 46:824-830.

- Vercellini P et al. Association between endometriosis stage, lesion type, patient characteristics and severity of pelvic pain symptoms: a multivariate analysis of over 1000 patients. Human Reproduction 2007; 22: 266-271.

- Ozkan S, Murk W, Arici A . Endometriosis and Infertility- Epidemiology and Evidence-based Treatments. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 2008.1127: 92-100.

- Hughes EG et al. A quantitative overview of controlled trials in endometriosis-associated infertility. Fertil Steril. 1993. 59: 963-970.

- Practice committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Endometriosis and infertility. Fertil Steril. 2004; 81: 1441-1446.

- Barratt CL et al.1990. Donor insemination – a look to the future. Fertil Steril. 54: 375-387.

- Coccia M et al. Impact of endometriosis on in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer cycles in young women: a stage-dependent interference Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 2011 Nordic

Federation of Societies of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2011; 90: 1232-1238. - D’Hooghe TM, Debrock S, Hill JA, Meuleman C. Endometriosis and subfertility: is the relationship resolved? Semin Reprod Med 2003; 21: 243–54.

- Brosens I. Endometriosis and the outcome of in vitro fertilization. Fertil Steril. 2004; 81:1198-1200.

- Matalliotakis IM et al. Women with advanced-stage endometriosis and previous surgery respond less well to gonadotropin stimulation, but have similar IVF implantation and delivery rates compared with women with tubal factor infertility. Fertil Steril. 2007; 88:1568-72.

- Lebovic DI, Mueller MD, Taylor RN. Immunobiology of endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2001 Jan;75(1):1-10. Review.

- Ziegler D, Borghese B, Chapron C. Endometriosis and infertility: pathophysiology and management. Lancet 2010; 376: 730-38.

- Lam A, Bignardi T, Khong SY. Surgical Therapies: Principles and Triage in Endometriosis, 387-395. Endometriosis: Science and Practice. Giudice L, Evers J, Healy D. March 2012, Wiley-Blackwell.

- Duffy J, Arambage K, Correa F, Olive D, Farquhar C, Garry R, Barlow DH, Jacobson TZ. Laparoscopic surgery for endometriosis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2014, Issue 4.

- Law K, Lyons S. Comparative Studies of Energy Sources in Gynecologic Laparoscopy. Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology 2013; 20: 308-318.

- Wykes CB, Clark TJ, Khan KS. Accuracy of laparoscopy in the diagnosis of endometriosis: a systematic quantitative review. Brit J Obstet Gynaecol 2004; 111:1204-1212.

- Kennedy S et al. ESHRE Special Interest Group for Endometriosis and Endometrium Guideline Development Group. ESHRE guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of endometriosis. Hum Reprod 2005; 20:2698-2704.

- Sinha UK, Gallagher LA. Effects of steel scalpel, ultrasonic scalpel, CO2 laser, and monopolar and bipolar electrosurgery on wound healing in guinea pig oral mucosa. Laryngoscope. 2003; 113:228-236.

- Koninckx PR, Ussia A, Adamyan L, Wattiez A, Donnez J. Deep endometriosis: definition, diagnosis, and treatment. Fertil Steril. 2012; 98:564-571.

- Jacobson TZ, Duffy JM, Barlow D, Farquhar C, Koninckx PR, Olive D. Laparoscopic surgery for subfertility associated with endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010; 1: CD001398.

- Wright J et al. A randomized trial of excision versus ablation for mild endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2005; 83:1830-6.

- Healy M, Ang C, Cheng C. Surgical treatment of endometriosis: a prospective randomized double-blinded trial comparing excision and ablation. Fertil Steril. 2010; 94:2536-40.

- Healy M, Cheng C, Kaur HTo excise or ablate endometriosis? A prospective randomized double blinded trial after 5 years follow-up. MIG 2014 (accepted for publication).

- Falcone T, Wilson J. Surgical Management of Endometriosis: Excision or ablation. JMIG 2014 (accepted for publication).

- Marcoux S, Maheux R, Berube S, the Canadian Collaborative Group on Endometriosis. Laparoscopic surgery in infertile women with minimal or mild endometriosis. New England Journal of Medicine 1997; 337(4):217–22.

- Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio dell’Endometriosi. Ablation of lesions or no treatment in minimal-mild endometriosis in infertile women: a randomized trial. Human Reproduction 1999;14(5): 1332-4.

- Johnson N, Hummelshoj L. Consensus on current management. of endometriosis. Human Reproduction, Vol. 28, No. 6 1552-1568, 2013.

Leave a Reply