On 9 July 2002, women around the world awoke to bold newspaper headlines and strident radio and television journalists trumpeting the harms of hormone replacement therapy (HRT), following the release of the first publication of data from the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) randomised controlled trial (RCT).

The Sydney Morning Herald, under a banner headline ‘Hormone alert for cancer’, declared ‘up to 600 000 Australian women had been advised to stop taking HRT as new research revealed it increases their risk of cancer’. The article went on to say: ‘The Cancer Council of NSW has called for women’s access to HRT to be restricted’.

Women’s Health Initiative was commissioned by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) in 1991 and sought to address the most common causes of death, disability and impaired quality of life in postmenopausal women. It was the largest US prevention study of its kind, costing upward of US $725 million and running for 15 years.

There were three components:

- a randomised controlled clinical trial of promising, but unproven, approaches to prevention;

- an observational study to identify predictors of disease; and

- a study of community approaches to developing healthful behaviours

A total of 161 808 women aged 50–79 were recruited, of whom 68 132 were involved in clinical trials. The ‘unproven’ approaches to prevention included: dietary modifications, calcium and vitamin D supplementation, and HRT.

The HRT RCT was intended to test the hypothesis that women receiving HRT would have lower rates of coronary heart disease and osteoporosis-related fractures than the placebo group. A substantial body of observational data had suggested this would be the case.

It is important to note that the original protocol explained that WHI would recruit women older than those included in typical RCTs with about two-thirds of the cohort over 60 years of age and that follow up would be longer than any previous trial. The primary aim was to see what happened to women who commenced HRT at an older age. This was not a trial of symptomatic, recently postmenopausal women.

The investigators correctly noted that, while considerable evidence suggested bone and cardiovascular benefit from HRT for women in early menopause, there was little pertinent data about the effects of starting HRT later, especially after age 60. The significance of age at initiation of therapy seems then to have been lost on the investigators for almost a decade.

The first Women’s Health Initiative results were released at a press conference on 9 July 2002, before the publication of the paper in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) one week later. The data were rushed to the news media in what one commentator, Dr Scott Gottlieb, a former senior official with NIH, described as a ‘carefully orchestrated PR blitz’. Chaos ensued; women were told to ‘stop their HRT and go to their doctor’.

Doctors, except it seems some linked to cancer councils, had no access to the unpublished data for more than a week and few knew anything of the paper. Even the principal investigators of WHI did not have an opportunity to review the data prior to release. The data were not completely adjudicated and, in a breach of protocol, were not released in age cohorts.

HRT, it was said, caused cancer, thrombosis and dementia, worsened heart disease and did little to alter quality of life. Results were conveyed, sensationally, as relative, not absolute, risks and not all were statistically significant. Relative risk (RR) describes the degree of change in a risk over the baseline rate whereas absolute risk provides the actual number of cases increased or decreased in a given population. While initial RRs made for sensational reading the absolute risks were small, making them ‘rare’ in World Health Organization terminology. Poor understanding of this important difference led the Sydney Morning Herald, in an article published on 10 July 2002, to confidently report that women taking HRT would sustain 41 per cent more strokes, 29 per cent more heart attacks and 26 per cent more breast cancer.

The NIH Chief Investigator, Jacques Rossouw, told the press conference that the adverse effects applied to all women irrespective of age, ethnicity or disease status. In a remarkable example of hubris he was also quoted as saying ‘NIH was going for high impact with the goal to shake up the medical establishment and change their thinking about hormones’. He must have been delighted with the results of his efforts: many women ceased HRT at once. Doctors were frightened to prescribe such ‘dangerous’ medications and many harboured a sense of resentment against ‘experts’ who had promoted the benefits of the now ‘disgraced’ therapy.

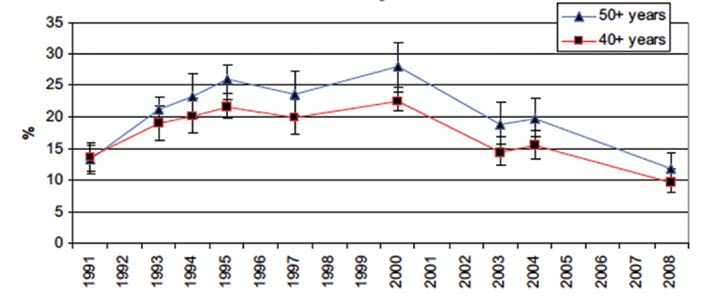

Figure 1. Current TGA – registered hormone therapy use.

In July 2002, approximately 25 per cent of recently postmenopausal women were current or past users of HRT. Most recent data suggest only six to seven per cent of US women and five per cent of Australian women in their 50s are current users (see Figure 1). Many women who abandoned HRT turned to complementary medicines or bio-identical hormones, which they perceived to be safer, but for which there were limited evidence of efficacy and no evidence of safety. In some, but not all, countries breast cancer incidence declined, plateaued and then began to rise again. By 2005, data had emerged to suggest that age-adjusted osteoporotic fractures had increased compared with 2001–2 and, in 2013, a paper using theoretical assumptions of prior and current oestrogen replacement therapy use estimated that up to 91 000 postmenopausal US women died prematurely because of avoidance of oestrogen therapy. And yet, in the ten years since Women’s Health Initiative researchers first unveiled their results, a series of follow-up studies using the same government data found that many of the initial conclusions were premature, indefinite or just plain wrong.

Critically, although the government initially said the findings applied to all women, regardless of age or health status, subsequent studies showed that the age of a woman and the timing of hormone use dramatically change the risk and benefits – just as the original protocol had postulated. In fact, the findings of these studies seem to directly contradict some of the government’s initial conclusions.

For example, women in their 50s who took a combination of oestrogen and progestin or oestrogen alone had a lower risk of dying than women who didn’t take hormones. Also, women in their 50s who regularly used oestrogen alone had a lower risk for severe coronary artery calcium, a risk factor for heart attack, a reduced risk of coronary heart disease and breast cancer and a reduced risk of all-cause mortality.

In 2013, the WHI investigators published results of long-term follow up from both arms of the trial. For women aged 50–59 or within ten years of their last menstrual period, there was no statistically significant increase in any adverse outcome for users of HRT. For users of oestrogen alone, risk of coronary heart disease, the commonest cause of death in postmenopausal women, was significantly reduced.

The anatomy of a health scare: headlines are not the place for nuanced reporting of complex results. (Clippings collected by the author.)

The WHI investigators and the NIH refused to share the raw data from the trial even with outside academics or the companies that manufactured the study drugs. They were thus able to protect their monopoly over the data and their prerogative to publish follow-up data as and when they saw fit. With the benefit of hindsight it seems likely, had the data been more widely shared, important analyses of the data that debunked original conclusions would have come to light much sooner to the benefit of postmenopausal women and their doctors.

‘The ultimate goal should be to help ensure that science and patient care are…free from the inappropriate influences of industry, government and politics.’

Governments now play increasing roles in the healthcare of patients, and the objectives of governments may at times be at odds with the interests of the individual patient and hence the professional obligations of their physician. Appropriately, greater transparency has been sought in the interaction of the pharmaceutical industry with physicians and similar transparency should also be applied to the interaction of governments with physicians. Author conflict-of-interest statements in journal articles should include funding received from industry or government agencies. Journals now maintain arms-length relations with the pharmaceutical industry and also with government sponsors. Journal editors should select reviewers for all manuscripts using similarly strict impartiality. Reviewers should review manuscripts with the same thoroughness, regardless of the funding source. The ultimate goal should be to help ensure that science and patient care are, to the extent possible, free from the inappropriate influences of industry, government and politics.

The role of the media release is also critical. A 1998 paper, published in JAMA, examining the source of newspaper articles on scientific topics, found 84 per cent referred to articles mentioned in press releases. In June 2002, a paper in JAMA entitled ‘Press Releases’ reported that in a survey of nine medical journals, involving 127 press releases, study limitations were rarely mentioned, industry (or government) funding was not mentioned and data were often presented using formats that may exaggerate the perceived importance of findings. The importance of a properly conducted press conference could not be better stated and yet, one month later, that same journal held the Women’s Health Initiative press conference, did not discuss study limitations or sources of funding and exaggerated the significance of findings.

Can it happen here? Yes, of course. Journals prosper not only from good scientific papers, but also from circulation, advertising and publicity. If you have a ‘newsworthy’ paper accepted, even by our own esteemed ANZJOG (of which I am an associate editor) you will be asked to consider a press release and offered the services of the publisher’s marketing department to make sure the impact is maximised. Of course, exaggerating your results will help!

- Women’s Health Initiative was a well-designed, large, long-running RCT to test the hypothesis that HRT given to older postmenopausal women would

reduce the burden of diseases of ageing. - Despite this, when the data were released, they were said to be applicable to postmenopausal women of all ages, ethnicities and health.

- The data were released before complete adjudication, without prior approval of all principal authors and before publication.

- Data were released in a sensational, confrontational manner to obtain maximum publicity and referred only to relative rather than

absolute risks. - Rigour was not evident in statistical analysis, nominal or adjusted confidence limits were not always correctly applied and results were

not always supported by statistical significance. - Failure of the government to release the raw data from the trial prevented independent analysis and may have delayed further

analyses that overturned many of the original findings. - Medical journals have a critical role to play in the dissemination of medical research. Strict authorship guidelines must be adhered

to. Reviewers must be diligent and independent, statistical analysis should be verified and significance of findings confirmed and data

presented in a clear concise manner. - Press releases should not be sent out before the paper has been published and is available to the medical profession; data should be

released in a factually honest manner. - Collaboration of bodies such as the Australian Science Media Centre, to assist journalists in the correct interpretation of scientific

data, should be considered.

References and further reading

- Writing Group for WHI. Risks and Benefits of Estrogen plus Progestogen in Healthy Postmenopausal Women. JAMA 2002; 288:321-333.

- Manson J et al. Menopausal Hormone Therapy and health outcomes during the intervention and extended stopping phases of the women’s health initiative randomized trials. JAMA 2013; 310:1353-1368.

- Pickar J. Conflict of Interest in Government funded studies. Climacteric 2015; 18:339-42

- Lobo R. Where are we 10 years after the women’s health initiative? JCEM 2013; 98:1771-1780.

- The WHI Study Group. Design of the Women’s Health Initiative Clinical Trial and Observational study. Controlled Clinical Trials 1998; 19:61-109.

- Parker Pope T The Hormone Decision. Rodale Press 2007

- Parker Pope T Wall St Journal, 9 July 2007, B1.

- Wiley Publishing. Advice for Authors. onlinelibrary.wiley.com .

- Semir V et al. Press Releases of Science Journal Articles and Subsequent Newspaper Stories on the same topic. JAMA 1998; 280:294-5.

- Woloshin S and Schwartz L. Press Releases: Translating Research into news. JAMA 2002; 297:2856-8.

- Islam S et al. Trend in incidence of osteoporosis related fractures among 40-69 yo women: analysis of a large insurance claims database. Menopause 2009; 16:77-83.

- Sarrel P et al. The mortality toll of estrogen avoidance: an analysis of excess deaths among hysterectomized women aged 50-59 years. Am J Public Health 2013; 103:1583-8.

Leave a Reply