The in-vitro fertilisation (IVF) research program began as a joint effort between Melbourne and Monash Universities at the Queen Victoria Hospital (QVH) and the Royal Women’s Hospital (RWH) in 1970, under the guidance of a committee chaired by Prof Carl Wood.

The initial team included Carl Wood, John Leeton and Alex Lopata from Monash University, and Ian Johnston and James Brown from Melbourne University – RWH. It was called ‘the egg project’.

The team produced the world’s first human IVF pregnancy in 1973. Nicknamed the ‘test-tube baby’, the team took an egg from a 36-year-old woman and fertilised it in a test tube; three days later, the embryo was implanted in her womb.

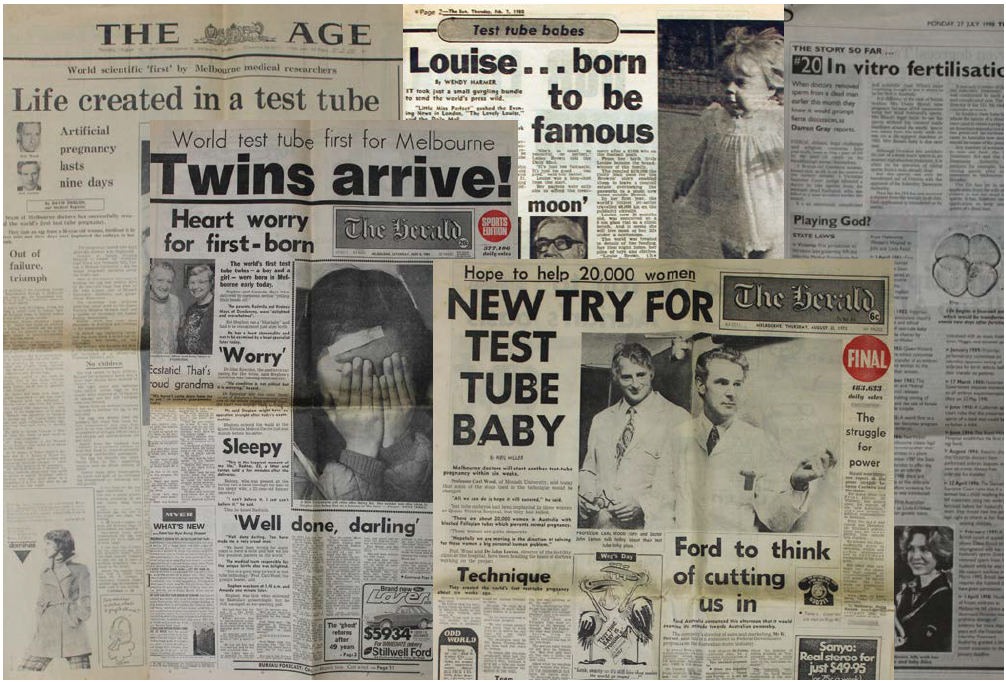

The pregnancy lasted nine days after the implantation – classified as a biochemical pregnancy, meaning that the pregnancy test was definitely positive – but it did not progress further. This revolutionary research was published in the Lancet. A few weeks later the front page from the Herald on Thursday 20 August 1973 (on display in the College museum), outlined the plans to progress with further attempts to achieve successful pregnancies, with photos of Carl Wood and John Leeton.

Despite continuing attempts for several years, no further pregnancies were obtained. However, these early results sparked excitement in fertility treatment and spurred on other research teams, particularly in the UK, where Robert Edwards had been working on the collection and maturation of human eggs in vitro since the 1960s. At the time, the only treatment for fallopian tube blockage was surgery with very limited success, and most women with blocked tubes were unable to become pregnant.

In 1977, a substantial grant was received by the Melbourne team from the Ford Foundation; who were keen to support the project as they thought the basic scientific information obtained may help in the development of new contraceptives. However, they did not want to be acknowledged if an IVF birth occurred. This grant allowed Alan Trounson, a scientist with experience in animal IVF in both Australia (in Jerilderee where he worked with Prof Moore on sheep IVF) and the UK, to be recruited to join the team.

In 1976 Steptoe and Edwards achieved a pregnancy in the UK, albeit an ectopic tubal pregnancy where the embryo implanted in the fallopian tube.1 Finally, in 1978, the first human IVF birth (Louise Brown) was reported by Steptoe and Edwards in the UK after 102 attempts at embryo transfer 2(followed by a second birth, Alastair McDonald, which was achieved in January 1979).

Hearing about the British success, the Melbourne team approached IVF with new vigour. Even before there was any real success, Trounson commenced publishing articles on the new knowledge gained, such as the application of IVF to unexplained subfertility.3

The combined team achieved the third IVF birth in the world and the first ongoing pregnancy in Australia. The front page of the Sun from 7 February 1980 shows Ian Johnston holding a media conference announcing the pregnancy at five months, and this can also be seen in the College Museum in Melbourne. The paper also shows photos of the other long-term members of the team, Carl Wood, Alex Lopata and John Leeton.4 Candice Reed was subsequently born in June 1980, at the RWH.

The teams then split, the team at the RWH including Johnston, Lopata, Spiers and McBain, and the Monash team working at the QVH with Carl Wood, John Leeton, Alan Trounson and myself. James (Mac) Talbot, who was involved with the 1973 pregnancy and who had an appointment in the Infertility Clinic at QVH, rejoined the team later.

The Monash team achieved no pregnancies at the QVH and moved to St Andrews Hospital in 1980. In natural cycles with only one follicle and laparoscopic oocyte collections, the procedure often took over an hour. As the cycles were done with spontaneous ovulation, the women had to be monitored 24 hours around the clock (with three hourly urine specimens) looking for a rise in luteinising hormone (LH). The time for oocyte collection was then 36 hours later, and often at 2am, 4am or 6am. Being an IVF clinician was like being an obstetrician – working all hours. The theatre staff were not happy to be called in for an operation that so far had no proven results. The follicle had to be visualised and often these women had pelvic adhesions and/or endometriosis, it was then aspirated, irrigated (flushed) and curetted with the needle, while trying not lose the oocyte, quite a challenge. If we managed to collect the oocyte, it was almost a celebration. Then this single oocyte had to fertilise and develop, and ultimately implant. Our instruments were simple, the embryo transfer catheter made of stainless steel and traumatic. At the instigation of Alan Trounson, we started using stimulated cycles using the hormone clomiphene citrate. This resulted in multiple follicles developing rather than only the one in a spontaneous cycle, giving a better choice of growing embryos for transfer.

Beresford Buttery commenced scanning our patients to monitor follicular growth, using transabdominal approach with a full bladder. Peter Renou joined the team and designed Teflon lined needles to laminar flow, and a much higher oocyte retrieval rate.5 By using stimulated cycles and better equipment – including a soft embryo transfer catheter – during 1980, we achieved 18 pregnancies, resulting in nine births, all conceived at St Andrews Hospital, but delivered at the Queen Victoria Medical Centre.6

Figure 1. Clipping from the Jones report, thanking the Melbourne teams.

The first baby delivered from such a stimulated cycle, by Beresford Buttery, was ‘Baby Victoria’, who remained anonymous, born just after the Labour Day weekend. The story, including a photo of John Leeton, only made page six of the Herald on 14 March 1981, and is also on view in the College Museum.

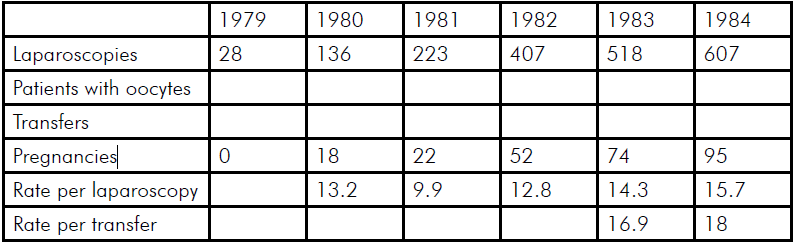

The demand on patients was tremendous. They had to stay in hospital for ten to 14 days, be monitored three hourly around the clock, undergo a prolonged laparoscopy and, after embryo transfer, spend 24 hours flat on their backs not moving, using bedpans and having a liquid diet, all for a procedure with a very low chance of success. Fortunately, the pregnancy rate rose from about ten per cent to 15 pre cent over five years. In 2013, the average IVF success rates in Australia for a fresh embryo transfer leading to a live birth varied from 39.4 per cent for women under 30 years of age using their own eggs to 9.2 per cent for women aged from 40–44 using their own eggs.7 Monash IVF results 1979 to 1984 are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. IVF pregnancy rates.

A number of world firsts followed, including the world’s first IVF twins, which made the front page of the Herald on the 6 June 1981, together with a photo of the proud grandparents! This again can be viewed in the Museum at College House.

In 1983, the Monash team achieved and delivered the world’s first human frozen embryo IVF pregnancy and the birth was written up as a feature in New Idea on 21 April 1984. A copy of the front page is displayed in the Museum.

Figure 2. A selection of just some of the newspaper stories held by the College Museum – many of which are on display.

The Melbourne teams were visited by many international scientists and clinicians, including Ed Worthem from Norfolk, Virginia, who was the scientist in the team led by Howard Jones that achieved the first IVF birth in the US in December 1981. Jones graciously acknowledged the help from the two Melbourne teams in his report of their pregnancies.

In 1982 we organised the first IVF workshop in the world, attended by 43 registrants who had come from every continent. The attendees included Andre van Steirteghem, who led the team that revolutionised insemination by developing intra-cytoplasmic sperm injection. We thought we were very entrepreneurial, charging a registration fee of $500 for the 14-day, hands-on course. I compare this to the one-day business management workshops now held with a $3000 registration fee!

Although IVF was originally developed to treat women with blocked tubes, male subfertility became a major part of the program. It became apparent that many men who could not impregnate their wives naturally had sufficient sperm to fertilise their eggs in vitro. The ‘male factor’ group was established with David DeKretser as the andrologist; Chris Yates, scientist and PhD student; Jillian McDonald as the IVF nurse; and myself as the IVF clinician coordinator.

Various sperm preparations were tried, including percoll and microdrops, to get a better sperm sample. Peter Temple-Smith, anatomist and scientist, and Graeme Southwick, plastics microsurgeon, joined and the group and helped achieve the world first birth from surgically recovered sperm from the epididymis of a man who had a previous vasectomy: Baby Joseph.

Concurrently, Alan Trounson and Geoff Mann were experimenting with microinjection of sperm under the zona pellucida (subzonal sperm injection [SUZI]). After attempting the technique on a couple, the Victorian Health Minister at the time, Ms Caroline Hogg, instructed the team not to continue with the technique. SC Ng who was working at Monash University with Mann and Trounson, returned to Singapore, and achieved the first human pregnancy and birth with SUZI using the Monash Technique in 1988 at the University of Singapore.8

Other techniques that were pioneered under Alan Trounson and Carl Wood’s directorships were in vitro maturation of oocytes and blastocyst culture. The team made a significant contribution to the technique of embryo biopsy and fluorescent in situ hybridsation (FISH) for pre-implantation genetic diagnosis (PGD). Leanda Wilton was part of the team developing the technique and subsequently was a member of the Hammersmith Group, under Robert Winston and Alan Handyside, that produced the world’s first PGD pregnancy.

Other developments at Monash IVF included the application of the microinjection fallopian transfer (MIFT), where oocytes were injected with sperm and then replaced laparoscopically into the fallopian tubes. This technique soon became obsolete.

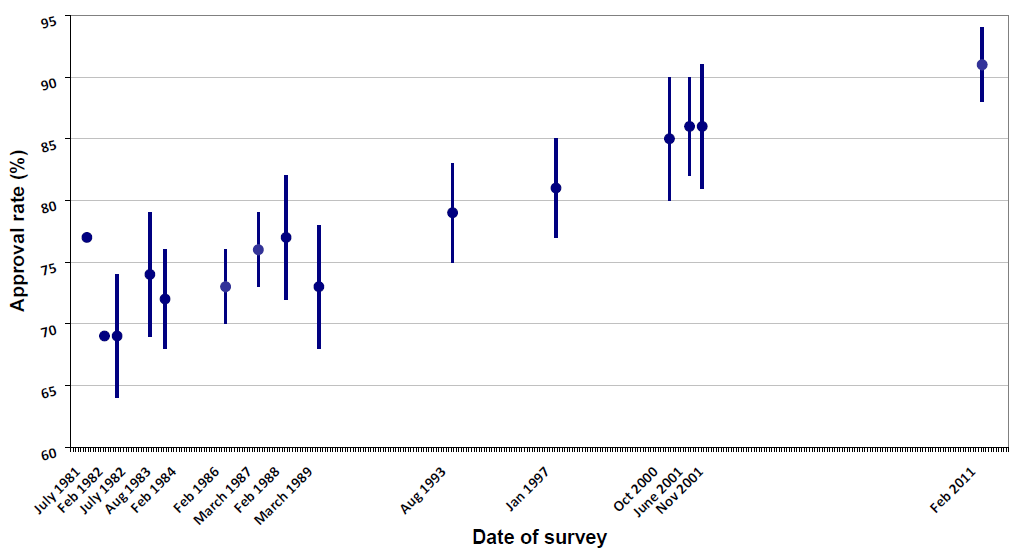

Although there was general enthusiasm from the public about Australia leading the world, there was also vocal opposition from some parts of the community, especially the Catholic Church and feminists. In order to assess attitudes, a number of Community Gallop Polls were undertaken by Morgan Gallop Polls. A summary of the approval rates from 12 polls over a 30-year period were published in ANZJOG.9 This shows that after initial enthusiasm, with 77 per cent of the community supporting IVF the controversy about embryo freezing, donation and biopsy resulted in a decline of support, followed by a steady recovery with IVF becoming more common and accepted. Current support for IVF to help sub-fertile couples is well over 90 per cent (see Figure 3). This is fortunate as nearly four per cent of babies born in Australia today were conceived by IVF.

Figure 3. Community support for IVF, surveyed over time.9 Reproduced with permission.

The whole process has changed dramatically. With use of GnRH agonists, and later antagonists, ovulation can be controlled, monitoring minimised, and, if needed, cycles can be programmed for the approximate day with the use of oral contraceptives and oocyte collections scheduled for convenient hours. Women only have to attend one or maybe two ultrasounds, many units have abandoned hormone assays and oocyte collection is performed as a short-stay procedure by transvaginal ultrasound-guided aspiration with minimal sedation. The transfer of just a single embryo has become almost routine and we no longer see the obstetric disasters of multiple pregnancies.

IVF is now not only used for treatment of subfertility, but also for the elimination of genetic diseases, where pre-implantation genetic diagnosis can be undertaken and embryos shown to be affected not replaced. It has a place in fertility preservation for women undergoing chemotherapy or radiotherapy, either by standard IVF and oocyte or embryo preservation, or by the technique of ovarian tissue cryopreservation with auto transplantation and subsequent IVF. Its role in social fertility preservation is still debatable, but the technique is now widely practised around the world.

What started as an innovative hypothesis in the 1970s has now become an everyday clinical treatment available not only in every capital city in Australia, but also at many regional centre.

References

- Steptoe PC, Edwards R G. Reimplantation of a human embryos with subsequent tubal pregnancy. Lancet 1976; 1(7965):880-2.

- Steptoe PC, Edwards RG Birth after the reimplantation of a human embryo. Lancet. 1978; 2(8085):366.

- Trounson AO, Leeton JF, Wood C, Webb J, Kovacs G. The investigation of idiopathic infertility by in vitro fertilization. Fertil Steril. 1980; 34:431-8.

- Lopata A, Johnston IW, Hoult IJ, Speirs AI. Pregnancy following intrauterine implantation of an embryo obtained by in vitro fertilization of a preovulatory egg. Fertil Steril. 1980; 33:117-20.

- Renou P, Trounson AO, Wood C, Leeton JF. The collection of human oocytes for in vitro fertilization. I. An instrument for maximizing oocyte recovery rate. Fertil Steril. 1981; 35:409-12.

- Wood C, Trounson A, Leeton JF, Renou PM, Walters WA, Buttery BW, Grimwade JC, Spensley JC, Yu VY. Clinical features of eight pregnancies resulting from in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer. Fertil Steril. 1982; 38:22-9.

- Macaldowie A, Lee E, Chambers GM. Outcomes of autologous fresh cycles by women’s age group, Australia and New Zealand, 2013. Assisted reproductive technology in Australia and New Zealand 2013. Sydney: National Perinatal Epidemiology and Statistics Unit, the University of New South Wales. 2015

- Sathananthan AH1, Ng SC, Trounson A, Bongso A, Laws-King A, Ratnam SS. Human micro-insemination by injection of single or multiple sperm: ultrastructure. Hum Reprod. 1989; 4:574-83.

- Kovacs GT, Morgan G, Levine M, McCrann J. The Australian community overwhelmingly approves IVF to treat subfertility, with increasing support over three decades. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2012; 52: 302-4.

Leave a Reply