“…her evidence indicates that it was her policy to withhold information about the risk of shoulder dystocia from her patients because they would otherwise request caesarean sections…”

Lords Kerr and Reed commenting on the obstetrician’s modus operandi to disclosure of risks in antenatal care.1

‘Informed consent’ is one of two fundamental preconditions for doctors undertaking actions that would normally be classified as criminal acts, typically as trespass or assault. The other precondition is ‘indication’, that is, a valid medical reason or justification for intervention.

Both preconditions are subject to a number of influences we often fail to consider. Indication is the easier of the two, since it is almost exclusively determined by objective, scientific fact and professional consensus. However, it is important to recognise that indication is not static, given that scientific progress will alter the limits of what is accepted professionally as ‘good medicine’. Fast progress in medical knowledge can necessarily lead to a mismatch between the scientific state of the art and current practice. The greater the mismatch, the greater the medicolegal risk for the practitioner. We contend that, at this point in time, the issue of maternal birth trauma is an excellent example of such a mismatch.

The situation is even more complicated for the precondition of consent. Importantly, informed consent also requires that scientific progress be taken into account. We are obliged to provide up-to-date and accurate information for consent to become truly informed, and we all know how precarious that distinction may be. However, when it comes to informed consent, we are also beholden to another set of professional influences that are entirely outside our control: the law.

The law is subject to the same societal influences as medicine, and it is at least as fluid, even though some components of it have been in place for millennia. The fluidity of the law and its application in medical practice is most evident in highly charged areas such as termination of pregnancy and surrogacy/assisted reproduction. Legislation and judiciary decisions necessarily reflect the zeitgeist; the ‘spirit of the times’. Things that were once legal become illegal, and vice versa.

Recent changes to the legal meaning of obstetric informed consent

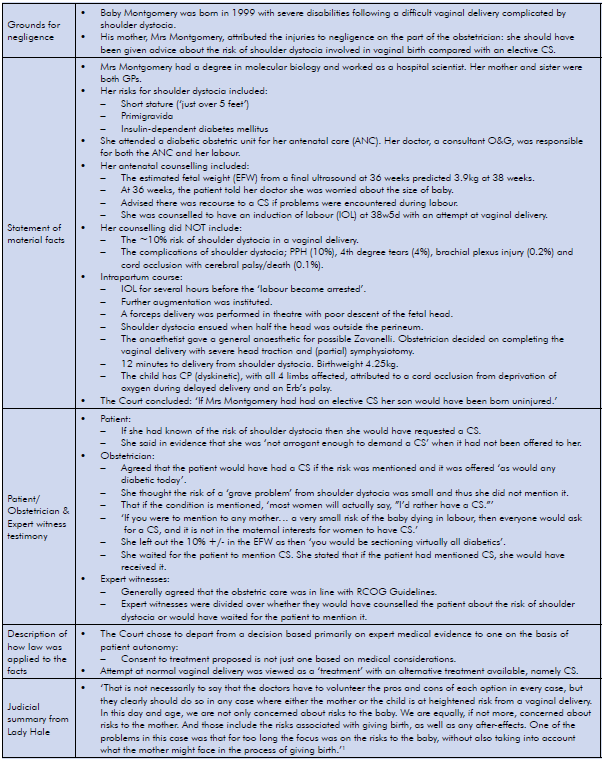

Occasionally the judicial system throws up something unexpected, which produces a reflection of the zeitgeist that changes the rules of the game altogether. This is what occurred in March 2015 with the Montgomery v Lanarkshire decision of the UK Supreme Court2, which is the motivation for this piece (see Table 1).

Table 1. Montgomery (Appellant) v Lanarkshire Health Board (Respondent) (Scotland) [2015] UKSC 11 On appeal from: [2013] CSIH 3; [2010] CSIH 104.

Since there are a multitude of complications of an attempt at vaginal birth that are very common at well above 1:100 and highly likely to be considered material by pregnant women, such risks now need to be disclosed in order to ensure that maternity care is of a defensible standard in the event of an adverse outcome. Most pregnant women (and their health professionals) would regard an emergency caesarean section (CS), forceps or a vacuum as a risk and a complication, even without the occurrence of postpartum haemorrhage (PPH), major perineal tears, levator tears or CS wound infections. Of equal import is the future morbidity associated with anal incontinence, prolapse, sexual dysfunction or psychological sequelae up to and including post-traumatic stress disorder.5

What does this mean in practice?

Obstetric consent, whether ante- or intrapartum, is a difficult subject. Unfortunately, antenatal education may be provided by staff who underplay the possibility of obstetric interventions. As a result, the information provided is often inaccurate and biased, and likely to be seen as such in a court of law. In the interest not just of risk management, but also as a requirement of medical ethics under the general principle of patient autonomy, it appears imperative that such information be provided by staff trained to undertake those procedures, that is, obstetricians or obstetricians in training, and well before a crisis in the delivery suite makes true informed consent impossible.

This is particularly crucial whenever several treatment options are available. The Supreme Court, in Montgomery v Lanarkshire, has stated unequivocally that ‘…doctors have to volunteer the pros and cons of each option in every case… where either the mother or the child is at heightened risk from a vaginal delivery.’6 One could add that the same necessarily applies to different forms of vaginal operative delivery.

Where there is limited provision of antenatal information, women are poorly prepared to participate in intrapartum decision-making, which is often emotionally difficult and under considerable time constraints. Operative delivery is a particularly important issue for consent, given the high probability of somatic maternal trauma.7 8 In most cases of vaginal operative delivery there is (at least theoretically) the option of CS, and in most cases of forceps there is the option of vacuum delivery, with the exception of uncommon scenarios such as the after-coming head or premature birth. In most instances it is difficult to argue that forceps is without alternative, given that entire countries, such as Denmark,9 have done without forceps for many years. Hence, the imposition of one option by the obstetrician, without discussion of alternatives, is potentially indefensible.

The issue of maternal trauma

Antenatal counselling of women who plan a vaginal delivery should include a reference to major pelvic floor trauma. The odds ratio of major tears of the levator ani muscle or ‘avulsion’, the main aetiological factor for pelvic organ prolapse,10 11 in forceps delivery compared to vacuum is about five. Vacuum does not seem to convey an increased risk compared to normal vaginal delivery (NVD).12 Anal sphincter tears are also much more common in forceps delivery compared to vacuum, with both more likely to lead to trauma than NVD.13 Pelvic floor and perineal trauma does not occur with caesarean delivery and needs to be discussed when considering delivery options.

Obstetric practitioners who are insufficiently aware of the true incidence and implications of obstetric maternal trauma act at their own medicolegal risk. Levator trauma was virtually unknown until recently, as it is usually occult. The first clinical description dates to 2007.14 Anal sphincter trauma is diagnosed increasingly commonly, but still appears to be overlooked more often than not. This may be due to truly occult trauma or poor diagnosis.15 16

Medicolegal consequences

Over the coming years there will be an increasing need to share information on the risk of perineal and pelvic floor trauma with patients (let alone risks such as shoulder dystocia in macrosomia, or stillbirth in VBAC) in order to offer a robust medicolegal consent procedure. This is particularly true since there is evidence of increasing institutional pressure to reduce CS rates.17 A push to reduce CS rates has the potential to justify more aggressive obstetric measures designed to achieve vaginal delivery, such as rotational forceps, longer second stages and an emphasis on VBAC.18 Demographic changes, especially increasing obesity and age at first delivery, make such aggressive obstetric practices increasingly dangerous to patients, and not just as regards pelvic floor morbidity.19 By definition, using the CS rate as a performance measure of obstetric services is a break with the traditional use of morbidity and mortality as undisputed key performance indicators.20 Treating the CS rate as such will inevitably result in increased morbidity and mortality, and likely, medicolegal claims. It is not surprising at all that law firms are starting to specialise in this field and market their services aggressively.21 We have allowed obstetrics to regress into practices that increase the likelihood of complications leading to medicolegal action precisely at a time when judicial innovation has reduced the likelihood of contemporary practice being successfully defended in court. As Montgomery v Lanarkshire has illustrated, this may involve the consequences of events that occurred many years in the past.22

We hope to have made clear that obstetric services are poorly prepared to deal with currently accumulating liabilities. The solution to the impending novel avenues of litigation (and the obvious way forward in terms of better risk management) is to focus on fulfilling our ethical, moral and medicolegal responsibilities as regards informed consent. Maternity care is anachronistic in terms of consent because we have been treating pregnant women like minors. This will have to change.

References

- Montgomery v Lanarkshire. Health Board. Supreme Court of the United Kingdom. 2015 [cited 2016 May 23]. Available from: www.supremecourt.uk/decided-cases/docs/UKSC_2013_0136_Judgment.pdf.

- Montgomery v Lanarkshire. Health Board. Supreme Court of the United Kingdom. 2015 [cited 2016 May 23]. Available from: www.supremecourt.uk/decided cases/docs/UKSC_2013_0136_Judgment.pdf.

- Rogers v Whitaker. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia. 1992 [cited 2016 May 23].1Available from: www. healthlawcentral.com/rogers-v-whitaker.

- Montgomery v Lanarkshire. Health Board. Supreme Court of the United Kingdom. 2015 [cited 2016 May 23]. Available from: www.supremecourt.uk/decided cases/docs/UKSC_2013_0136_Judgment.pdf.

- Skinner E, Dietz HP. Psychological consequences of traumatic vaginal birth. Neurourol Urodyn. 2015;34(S3):S170-171.

- Montgomery v Lanarkshire. Health Board. Supreme Court of the United Kingdom. 2015 [cited 2016 May 23]. Available from: www.supremecourt.uk/decided cases/docs/UKSC_2013_0136_Judgment.pdf.

- Dietz HP. Pelvic floor trauma in childbirth. ANZJOG. 2013;53(3):220-230.

- Dietz HP. Forceps: Towards obsolescence or revival? Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2015;94(4):347-51.

- Lowenstein E. Ottesen B, Gimbel H. Response to the letter to the editor by HP Dietz. Int Urogynecol J. 2015;26:1091.

- Dietz HP, Steensma AB. The prevalence of major abnormalities of the levator ani in urogynaecological patients. BJOG. 2006;113(2):225-30.

- DeLancey J, et al. Comparison of levator ani muscle defects and function in women with and without pelvic organ prolapse. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2007;109(2):295-302.

- Dietz HP. Forceps: Towards obsolescence or revival? Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2015;94(4):347-51.

- Friedman T, Eslick G, Dietz HP. Instrumental delivery and OASI. Int Urogynecol J. 2016; in print.

- Dietz HP, Gillespie A, Phadke P. Avulsion of the pubovisceral muscle associated with large vaginal tear after normal vaginal delivery at term. ANZJOG. 2007;47(4): 341-344.

- Andrews A, et al. Occult anal sphincter injuries – myth or reality? BJOG. 2006;113:195-200.

- Guzman Rojas R, et al. Prevalence of anal sphincter injury in primiparous women. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2013;42(4):461-466.

- Anonymous, Maternity – Towards Normal Birth in NSW, in PD 2010-045, N. Health, Editor. 2010, NSW Health: Sydney. Accessed on 23.5.16 at: www0.health.nsw.gov.au/policies/pd/2010/pdf/PD2010_045.pdf.

- Dietz HP, Campbell S. Towards normal birth- but at what cost? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;DOI10.1016/j.ajog.2016.04.021.

- Gardner K, et al. Improving VBAC rates: the combined impact of two management strategies. ANZJOG. 2014;54(4):327-332.

- Dietz HP, Pardey J, Murray H. Pelvic floor and anal sphincter trauma should be key performance indicators of maternity services. Int Urogynecol J. 2015;26:29-32.

- Third Degree Tears Solicitors. United Kingdom. Glynns Solicitors 2012 [cited on 2016 June 14]. Available from: www. thirddegreetears.co.uk/.

- Montgomery v Lanarkshire. Health Board. Supreme Court of the United Kingdom. 2015 [cited 2016 May 23]. Available from: www.supremecourt.uk/decided-cases/docs/UKSC_2013_0136_Judgment.pdf.

Leave a Reply