A significant aspect of the art of practising medicine is the ability to obtain genuine informed consent. Medical students learn in an apprenticeship model and how they observe their medical tutors obtaining a patient’s consent will greatly affect their future practice.

Obtaining consent

Although medical students are rightfully members of the healthcare team, it is important to understand that being given the opportunity to interview, examine and to possibly participate in a patient’s treatment is a privilege and the patient may withdraw his or her consent at any time. The primary responsibility for ensuring consent has been obtained lies with the medical practitioner, not the student. The consenting process should occur in an environment where the patient feels no pressure to provide consent and must occur before the student is involved in the patient’s management. As circumstances in the patient’s medical condition may change over time, the student should be aware that consent needs to be obtained for each instance of care.

It is quite appropriate to inform the patient that the medical student is a member of the healthcare team, but it is inappropriate to introduce the student as a junior colleague or young doctor. These euphemistic terms are misleading and may indicate to the patient that the student could possibly have some input into the decision-making process relating to his or her treatment.

The student should understand that an ethical consenting process not only provides protection for our patients, but also for the healthcare professionals involved with their care.

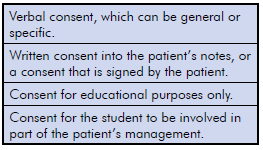

Types of informed consent

There are several types of informed consent, as shown in the box below:

In general, the nature of the consent will depend on the amount of involvement from the student and the potential risks to the patient. Therefore, verbal consent should be limited to history-taking, observation, non-sensitive examinations and basic procedures conducted under supervision.

Specific verbal consent should be obtained for procedures such as giving injections, intravenous cannulation or suturing. If the procedure would normally be recorded in the clinical notes, the consent should also be recorded. It is important that students do not undertake procedures on patients unless they have obtained the appropriate knowledge and skills training related to the procedure. All procedures should be supervised until the tutor is satisfied that the student is competent to perform the procedure unsupervised.

The difference between consent when a student undertakes an examination primarily for educational purposes, as compared to an examination which the student performs as part of the patient’s management, needs to be appreciated. For example, if a student in the operating theatre setting is directed by the surgeon to assist or perform an examination that directly relates to the patient’s management, as long as the patient is aware that a student will be working with the surgeon, verbal consent is adequate. However, if an examination or procedure is to be performed by a student solely for educational purposes, prior written consent must be obtained. This especially applies for intimate physical examinations such as vaginal, rectal or breast, when the examination is performed under anaesthetic.

Clinical settings

In broad terms, the clinical settings for obtaining consent fall into the two categories of inpatient and outpatient. Inpatient settings include emergency departments, intensive care units, operating theatres, birth suites, neonatal units, adult and paediatric wards and mental health units. Outpatient settings in the obstetrics and gynaecology area include clinician’s rooms or outpatient departments in hospitals. Each of these areas has unique requirements for consent.

In each of these settings, students should be readily identified as a medical student and a name badge indicating their status should be worn during times of patient contact.

In a clinician’s room, signage and pamphlets indicating that the practice is involved in medical student education is helpful in explaining the presence of the student and in assisting with the consenting process.

In my practice, administrative staff inform the patient on arrival of the presence of the medical student and ask the patient if they are comfortable with the student being present for the interview and/or examination. If the patient consents to having the student present, the student will then introduce themselves to the patient in the waiting room and again confirm that consent has been obtained for them to be present. When the patient enters for the consultation, I also confirm consent simply by verbally verifying that they have met my student and are happy for the student to be present. This process minimises the risk of the patient feeling pressure to give consent.

In the hospital environment, I have noted quite a variation in the protocols that students employ to obtain consent from the patient. At a minimum, a student should seek permission from an appropriate member of the patient’s healthcare team before entering the patient’s room to obtain their consent. They should always explain to the patient that they are a medical student, that there is no obligation to consent to the interview and/or examination, and that the patient can terminate the interview at any time.

The student should also have a low threshold for terminating the interview if the patient indicates any hesitancy regarding the interview and/or examination. The consent should be recorded in the patient’s chart or the student’s notes.

Areas of difficulty

Challenges arise in this process where the patient is temporarily or permanently unable to make informed consent. For example: neonates, minors, unconscious patients or patients with mental illness. There is also the category of patients that are not competent in the English language.

If possible in these circumstances, consent should be sought from their legal guardian, with the awareness that the person obtaining the consent should always address and respect culture, religion and language diversity. In some of these situations, student involvement may not be possible or may be restricted to observation alone.

A possible solution in such circumstances may be the inclusion of a statement in the admission form that indicates that medical student teaching is undertaken at this institution and that students may be involved in observation or patient procedures under supervision. The patient and or guardian can opt out at this time.

Confidentiality

As part of the consenting process, students should be made aware that they must respect the confidentiality of all patients and not discuss the clinical details of a patient, even in a de-identified manner, outside the clinical setting. This includes public places within the institution such as lifts, corridors and dining areas.

Conclusion

It has been my experience that the vast majority of patients are only too willing and happy to allow medical students to be involved in their care. It is therefore imperative that this privilege is not abused. Appropriate informed consent must be obtained for the student’s involvement, and our students must also understand the importance of this process.

Further reading

National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research.

Medical Students and Informed Consent. NZMJ May 15 Vol 128 No 1414.

Leave a Reply