As Dana Magdassi, a surrogacy lawyer from Ukraine, put it succinctly at the recent Australian Surrogacy Conference: ‘IVF is a medical process. Surrogacy is a legal process.’ At its best, surrogacy is an absolutely magical process. To hear a judge tell parents who have struggled with infertility for years that the child is theirs and to congratulate them is one of the most joyous experiences I could have as a lawyer. Informed consent to a surrogacy arrangement by the surrogate, her partner and the intended parents requires a range of information to be supplied: medical, psychological and legal.

Surrogacy regulation in Australia

Every state and the ACT allows altruistic surrogacy, and criminalises commercial surrogacy. Common features involve independent legal advice and psychological counselling/screening at the beginning, followed by consideration by the relevant IVF unit’s ethics committee. The Northern Territory has no laws concerning surrogacy, and its only clinic does not provide surrogacy services.

Each jurisdiction has invented slightly different wheels as to surrogacy regulation. For example, in Queensland and New South Wales, it is necessary to obtain an affidavit from the treating doctor to show that the intended surrogate (and if a lesbian couple, both women) is an eligible woman; and to show that conception occurred after the surrogacy arrangement was signed. The latter is helped by a world-leading case, LWV v LMH (2012),1 from Queensland, in which conception was held to be the act of pregnancy, not the act of fertilisation of the ova. In Victoria, by contrast, an affidavit by the doctor is not required, but a report by the doctor to the state regulator, the Patient Review Panel, is required before treatment can commence.

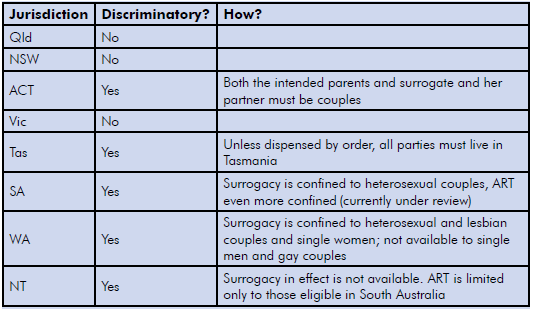

Table 1. Discrimination explained by state.

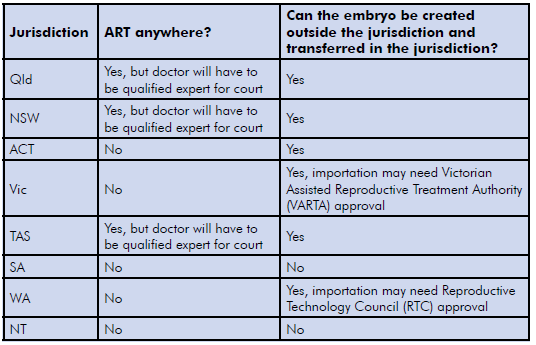

Doctors who practise in IVF must comply with the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Guidelines, plus other Commonwealth, state and territory law. Doctors who practise assisted reproductive technology (ART) in Victoria and Western Australia are burdened with the most detailed state laws.

Why Australians go overseas

Many Australians venture overseas not because they cannot find a surrogate or an egg donor, but because the law in their jurisdiction discriminates against them in their bid to be parents. While surrogacy is the option of last resort for heterosexual couples, it is the first and only option for gay couples and single men to become parents.

Aside from discrimination, the reasons clients report for going overseas are primarily that they cannot find surrogates or egg donors here. Sometimes they believe the stories they read on the web about overseas success stories. The numbers of children born overseas vary, between 200 and 1000 a year. The estimate given by a surrogacy advocate recently was that there were 35 children born locally via surrogacy in 2014, and in the same year 400 overseas.2Intended parents often view regulation of surrogacy here as being too uncertain, too costly, cumbersome and slow. The reality is that the legal regime in Australia is generally simpler, considerably cheaper and just as fast as anywhere overseas (I tell intended parents to expect the process to take between 18 months and four years, depending largely on medical issues). Intended parents might spend approximately $25 000–60 000 on a typical domestic surrogacy journey. An estimate for Canada is about $90 000, and greater in the USA.

Flexibility between states

Some states allow IVF to occur elsewhere. This has led to intended parents undertaking IVF for New South Wales arrangements in Queensland, for example, or Queensland and New South Wales intended parents accessing US egg donors and having the IVF there, and then obtaining surrogacy parentage orders in Queensland and New South Wales courts.

Importing embryos from overseas can be problematic, under both national and some state requirements.

Going overseas for surrogacy

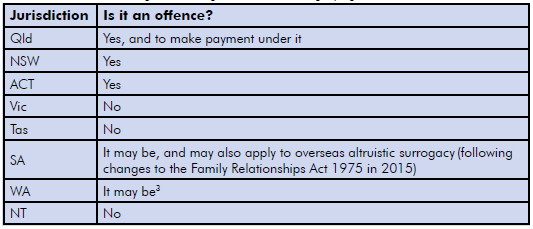

In advising patients that surrogacy is an option, doctors have to be careful not to commit offences when discussing overseas options. In Queensland, for example, to aid, abet, counsel, procure or to conspire with someone who will be committing a criminal offence, is also to be a principal offender. Other states have similar criminal laws. The maximum penalty for imprisonment is that of Queensland: up to three years. The maximum fine is in New South Wales: up to $110 000.

In two jurisdictions, there are two specific offences aimed directly at doctors and lawyers:

- In Western Australia it is an offence to provide a service knowing that it is to facilitate a surrogacy arrangement that is for reward (which includes overseas arrangements), except if the service is provided to the surrogate after she becomes pregnant.

- In Queensland it is an offence to provide a technical, professional or medical service to a surrogate in a commercial surrogacy arrangement (which includes overseas arrangements) before she becomes pregnant.

Table 2. Offences of entering into a foreign commercial surrogacy agreement.

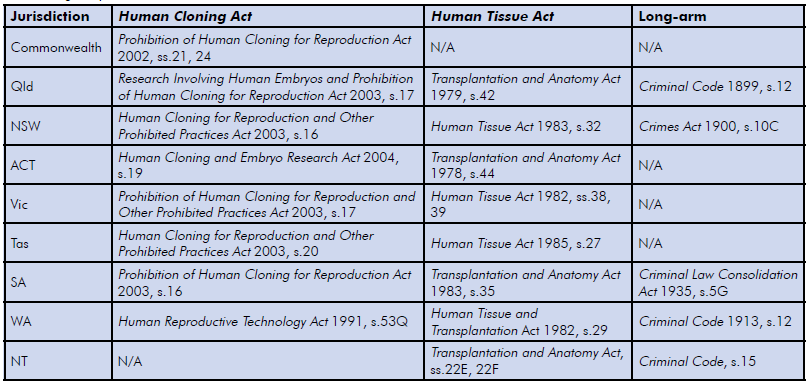

Going overseas for egg donation

Commonwealth, state and ACT Human Cloning Acts3 make it an offence, punishable by up to 15 years imprisonment, to pay an egg donor other than her out-of-pocket expenses. Because state and ACT Human Cloning Acts exist, many intended parents who have gone overseas for egg donation will have inadvertently committed the offence under the state legislation, by virtue of long-arm laws; that is to say that they stretch out from the state like a long arm, extending the jurisdiction. Similarly, state and territory long-arm provisions extend to the Human Tissue Acts, which prohibit the sale of eggs, sperm or embryos. Doctors who have advised those patients to go overseas for commercial egg donation may also have committed the same offence, by virtue of principal offender laws. With careful legal planning, it is possible for patients to avoid committing these offences. Doctors need to take care as to what steps they take and what they say to patients, to avoid committing the offences.

Table 3. Where can patients have ART for their domestic surrogacy arrangement?

Overseas altruistic surrogacy

Recently, I acted for a surrogate and her husband. My client was the surrogate for her sister and brother-in-law. A fairly straightforward arrangement, one might think. The complexity was that my clients lived in Adelaide and the intended parents lived in New Zealand. IVF was in the US. To enable this surrogacy to proceed, it required navigation of South Australian, Commonwealth, New Zealand and US law and the Hague Intercountry Adoption Convention. I drafted a surrogacy arrangement. It was non-compliant with South Australian law (because the intended parents did not live there, and because IVF did not occur there) and therefore an order could not be obtained in South Australia. However, the arrangement was legal. It was not commercial surrogacy, as the document made plain. An obstetrician in Adelaide was able to assist my client. The child was born, travelled to New Zealand, and lived with her parents. An order was made in a New Zealand court to recognise the intended parents as the parents. A good news story!

Table 4. Long-arm provisions.

What’s next?

It is likely that the number of domestic surrogacy arrangements will continue to rise, as intended parents realise surrogacy is available. However, the vast majority of intended parents will likely continue to go overseas, due to a shortage of (or perceived shortage of) surrogates and donors.

It is likely that any changes that might come about from the recent House of Representatives surrogacy inquiry will not alter the fact that most Australian intended parents will still go overseas for surrogacy,4 rather than at home. The inquiry has recommended making it more difficult for intended parents going to countries that don’t have Australian standards. That’s everywhere except the UK and New Zealand! It is unclear if Canada and the US will be in this category or not. The Committee recommended keeping the ban on commercial surrogacy, having national, non-discriminatory laws, and inquiring whether children born from donors and surrogacy have the names of the surrogates, donors and their partners on the children’s birth certificates.

The Committee has recommended a national surrogacy register, so that intended parents can find surrogates. In short, if these proposals were to work, for every surrogate available in 2014, 11 would have to be found each and every year thereafter to replace overseas surrogates. If the Committee’s recommendations were to be successful in this, it would be akin to the second miracle of the loaves and fishes.

For the last five years, the Hague Conference on Private International Law (of which Australia is a member) has looked at there being a Hague Convention in place concerning children, including international surrogacy arrangements. It remains unclear if there is going to be a convention, but my best estimate is if there is going to be a convention, it is likely to be three to five years away, and focused on the legal status of the child, more so than regulating how international surrogacy occurs. We shall see.

Finally…

Too often, I am told by clients that they have received insufficient advice by their treating doctor about the real chances of getting pregnant, and little to no information about surrogacy. As treating doctors owe a duty of care to their patients, sooner or later a patient who has undertaken innumerable IVF cycles will seek to sue her treating doctor for failure to give advice. It is only a question of time. Doctors should document the advice they have given to patients about the real chances of pregnancy, and other available options, including surrogacy.

References

- LWV & another v LMH [2012] QChC26, viewable at http://archive.sclqld.org.au/qjudgment/2012/QChC12-026.pdf. The author acted for the surrogate.

- www.smh.com.au/nsw/australian-surrogacy-laws-need-reform-say-advocates-20160523-gp1v0k.html.

- Prohibition of Human Cloning for Reproduction Act 2002 (Cth), s.21. An example of a mirror State Act: Human Cloning and Other Prohibited Practices Act 2003 (NSW), s.16.

- Everingham, et al., Australians’ use of surrogacy, Med J Aust. 2014;201(5):270-273.