The unusually early development of physical changes associated with puberty is known as precocious puberty. In girls, these changes are the development of breasts and pubic hair before eight years of age, or starting periods (menarche) before nine years of age. In boys, the changes are enlargement of the genitalia and development of pubic hair before nine years of age. Precocious puberty is thought to occur in 4–5 per cent of girls, but is much less common in boys.

Normal puberty

When a child’s body is ready to begin puberty, a part of the brain called the hypothalamus releases gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH). GnRH causes the pituitary gland to release two other hormones: luteinising hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH). LH and FSH stimulate the ovaries to produce oestrogen or the testes to produce testosterone, which lead to the changes you see during puberty. This process begins many years before secondary sexual characteristics first appear, which is usually between the ages of 10 and 13 years. In girls, the pubertal growth spurt occurs early in puberty, at the same time as breast development. In boys, the growth spurt does not occur until mid-puberty.

True precocious puberty

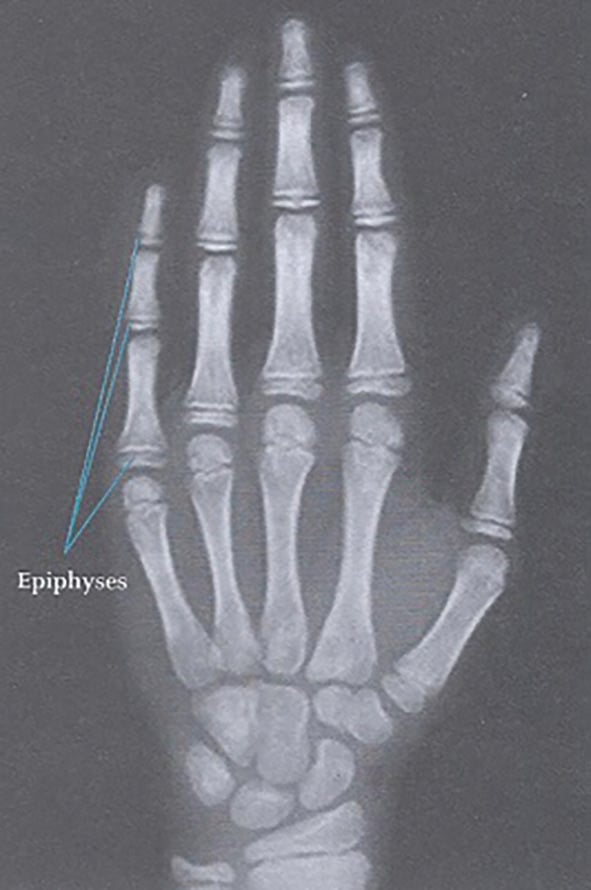

In true precocious puberty, sexual development shows a normal progression, but is earlier than usual. Children are taller than their peers due to the early pubertal growth spurt, and a bone age x-ray (x-ray of the left wrist and hand) will show advanced maturation of the skeleton as a result of increased oestrogen exposure (Figure 1). Although tall at presentation, these children may end up shorter than expected due to premature fusion of the long-bones and early completion of growth.

What causes precocious puberty?

There may be early activation of the neurons in the hypothalamus, resulting in increased production of GnRH or over-production of LH and FSH from the pituitary gland due to a pituitary tumour. The cause of early activation of the hypothalamus is generally unknown, although a structural brain abnormality is found rarely in girls and in approximately 50 per cent of boys. Causes may include hydrocephalus, benign and malignant tumors. Precocious puberty may be inherited; if a parent had precocious puberty, there is a strong chance that their child will show a similar pattern of development.

What investigations are indicated?

- A careful history and examination are essential. A growth assessment should include height, height velocity, weight and body proportions.

- A bone age x-ray should be done at the time of the first appointment to assess skeletal maturity.

Baseline hormone measurements performed in the outpatient department should include thyroid function tests, prolactin, IGF-1, LH, FSH and oestradiol. - A GnRH stimulation test is performed as a day case, with a stimulated LH >5IU/L being considered abnormal (sensitivity >98%, specificity 100%).

- In all girls, an ultrasound scan of the pelvis should be performed to assess uterine maturity and ovarian appearance.

- A magnetic resonance scan of the brain is routinely performed if precocious puberty is confirmed, although in children over eight years old the likelihood of finding any pathology is small. If there is a suggestion of an underlying disorder, additional tests may be required.

Figure 1. Bone age x-ray.

Who should be treated and why?

Endocrinologists have focused primarily on the impact of growth when considering treatment of precocious puberty. Using these criteria alone, not all children will require treatment as those with only slightly early puberty don’t end up shorter than expected. However, there is increasing evidence to suggest that early exposure to sex hormones can result in altered body image, behavioural problems and significant emotional distress. Young children can become very distressed at looking different from their peers and worry that something is wrong with them. Bullying and risk-taking behaviour can be a significant issue. Puberty can be challenging enough when it occurs at the normal time; for much younger children, puberty can cause a great deal of anxiety and distress.

What treatment is available?

GnRH analogues, such as luprolide (Lucrin) and goserelin (Zoladex), suppress the natural GnRH production. This blocks the release of LH and FSH from the pituitary, stopping and reversing the physical and psychological changes seen in precocious puberty. They are given as an intramuscular injection (luprolide) or subcutaneous implant (goserelin) every three months. In our centre, monitoring is performed by three- to six-monthly clinical assessment of growth and pubertal stage, annual bone age x-ray and by measuring gonadotrophin levels one hour after depot injection annually. On treatment, a child’s growth will slow to a normal prepubertal rate of approximately 5cm per year. Treatment can be continued until it is a more appropriate time for puberty to occur, generally between 10 and 11 years. Once the treatment is discontinued, puberty will progress normally and menarche is usually reached within 12–18 months.

Potential complications of treatment

Mild side-effects, such as headaches, mood changes, rashes and local irritation, are relatively common. Some girls may experience some vaginal bleeding early in the treatment as a result of oestrogen withdrawal. Weight gain and polycystic ovarian syndrome are more common in women with precocious puberty; however, there is some doubt as to whether this is due to the treatment or the condition itself.

Other common variants of pubertal development

Isolated early breast development (premature thelarche) commonly presents before the age of three years, with unilateral or bilateral breast development. Growth is normal and there is no other evidence of oestrogen excess. It is important to differentiate this from true precocious puberty as it is a harmless self-limiting condition that generally resolves within 1–2 years and requires no treatment.

Premature adrenarche occurs in girls and boys between six and nine years of age and presents with pubic hair. This is a common variant and affected children may have increased speed of growth and a slightly advanced bone age. This condition is occasionally due to underlying abnormalities of the adrenal gland, such as 21-hydroxylase deficiency, therefore investigations such as an androgen profile (including a 17 OHP level, DHEAS and testosterone) and a bone-age x-ray are indicated. Once pathology is excluded, the child and their family can be reassured that although the pubic hair will remain, the rest of puberty is likely to occur at the normal time.

Isolated premature menarche can occur at the onset of normal puberty, when small amounts of oestrogen are produced as the ovary switches on and off. Sometimes this can be enough to thicken the endometrium, which results in a withdrawal bleed when the ovary ‘switches off’. In affected girls, growth is normal, with no advancement in bone age or other signs of oestrogen excess. Other endocrine and local causes of vaginal bleeding must be sought and a basic work-up may include a bone age x-ray, gonadotrophins and oestradiol, GnRH stimulation test (pre- and post-stimulation gonadotrophin and oestrogen levels), coagulation profile and a pelvic ultrasound. Long bone x-rays may be considered if there is clinical suspicion of McCune-Albright syndrome (gonadotrophin-independent autonomous ovarian function caused by an activating mutation of the GNAS1 gene). Most girls have a few isolated episodes of bleeding that stop spontaneously, although some may continue to have periods into adulthood. Unlike true precocious puberty, these children do not demonstrate an abnormally advanced bone age, and their final adult height is unaffected.

Further reading

Sperling, MA. Pediatric Endocrinology. 3rd Edition. 2008. Saunders, Elsevier.

Kim HK. Gonadotropin-releasing Hormone Stimulation Test for Precocious Puberty. Korean J Lab Med. 2011;31(4):244-49.

Utriainen P, Laakso S, Liimatta J, et al. Premature Adrenarche – A Common Condition with Variable Presentation. Horm Res Paediatr. 2015;83:221-31.

Ejaz S, Lane A, Wilson T. Outcome of Isolated Premature Menarche: A Retrospective and Follow-Up Study. Horm Res Paediatr. 2015;84(4):217-22.

Australian Paediatric Endocrine Group. Hormones and Me Booklet Series. Available from: https://apeg.org.au/patient-resources/hormones-me-booklet-series.

Leave a Reply