This case report highlights a rather uncommon, yet important, complication of caesarean section: Ogilvie’s syndrome (OS). This syndrome describes the phenomenon of an acute colonic pseudo-obstruction, often without an obvious mechanical cause. The obstruction can then lead to bowel perforation or ischemia.

OS carries the name of the British surgeon Sir William Heneage Ogilvie who first reported it in 1948, following observation of two of his patients with metastatic cancer.1 He describes the clinical scenario of acute massive dilatation of the colon with no mechanical obstruction of the distal colon.

OS remains an under-recognised condition. Its true incidence is a mystery; partly as mild cases tend to resolve spontaneously. Furthermore, there is no reliable national or international data to suggest its frequency.2 However, delays in diagnosis have a significant direct correlation with mortality rates. It has been suggested that there is a 15 per cent mortality rate in healthy patients who receive early intervention with no complications compared to 36–50 per cent mortality rate in cases where there is a perforation or ischemic bowel.3

OS does not have any age predilection, although it is observed more often in elderly patients as well as those with multiple comorbidities. It has a male-to-female ratio of 1.5:1.4 In the obstetrics setting, caesarean section is noted to be the most common procedure associated with OS, although it has also been reported to occur following vaginal birth and forceps-assisted delivery.4 5 6 The UK Confidential Enquiry into Maternal and Child Health 2000–2002 report mentioned four deaths from OS, all following caesarean section. 7

Despite the rising rate of caesarean sections being performed worldwide, OS remains a relatively rare condition that requires prompt recognition. Clinically, it is rather challenging to differentiate between OS and paralytic ileus in the initial stage.

Case report

We present the case of a 19-year-old G1P0 with an uncomplicated singleton pregnancy. She was admitted for induction of labour due to post-dates at 41 weeks and was induced with 1mg of Prostin gel followed the next day by artificial rupture of membranes, which showed the presence of light meconium-stained liquor. Her labour was augmented with Syntocinon and routine labour monitoring was commenced with no abnormal recordings throughout labour. Of note, she was positive for Group B Streptococcus and had asymptomatic sinus tachycardia.

Following 12 hours of active labour with good progress initially, she had secondary arrest at 8cm of cervical dilatation with a reactive cardiotocograph and the baby was found to be in direct occiput-posterior position. Subsequently, a category 2 emergency caesarean section for failure to progress was called.

Caesarean section went smoothly, with abdomen entered via Joel Cohen technique; peritoneal cavity and pelvic organs appeared normal. No electrocoagulation instruments were used during the procedure. The baby was delivered via Wrigley’s forceps, weighing 4.5kg. The Apgar score was 9 at one minute and 9 at five minutes. The estimated blood loss was 500ml. No bowel or bladder injury was observed intra-operatively.

Post-operatively, her recovery was slow and she experienced abdominal distension and mild pain on the second post-operative day, but was tolerating a normal diet by the third day. Although bowel sound and distended abdomen were documented on days 3 and 4, she had opened her bowels on day 3, so no further investigations were carried out. She requested to be discharged home on day 4.

She presented to the emergency department on Day 6 with recurrent vomiting, pyrexia, generalised abdominal pain, significant distension and also specifically mentioned bilateral shoulder tip pain. She also mentioned that she did open her bowel, but it was different from her normal routine and her abdomen was so distended that she felt that she was ‘pregnant again at 40 weeks’. Despite these symptoms, she had been breastfeeding and bonding well with baby.

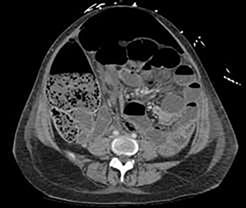

Figure 1. Multiple air fluid level seen with possible faecal loading.

Her blood results came back with markedly elevated CRP of 612 and white cell count of 12.1 x 109/L. Abdominal x-ray showed distended loop of small and large bowel with positive Rigler’s sign, suggestive of perforation. This was confirmed on CT scan, which showed distended ileum with free intra-abdominal fluid and gas collections.

An emergency laparotomy was performed through the previous Pfannensteil incision; however, a midline laparotomy was necessary due to the extent of faeculent soiling of the peritoneal cavity. A perforated caecum was found and a right hemicolectomy with ileostomy was performed. Approximately five litres of faecal-purulent fluid was drained and the abdominal wound was left open with a negative pressure (VAC) dressing and a further washout and full closure was performed the next day. Histology of the resected colonic segment showed full thickness necrosis, perforation and findings consistent with caecal pseudo-obstruction.

She was admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) after her initial operation. A few days later, she underwent a repeat laparotomy for recurrent sepsis. A VAC dressing was applied over the open abdomen. She was returned to ICU mechanically ventilated, requiring vasopressor therapy. The next day, the Pfannenstiel incision was re-opened due to purulent discharge and superficial dehiscence. After further abdominal washout, the abdominal fascia was closed with a VAC dressing. Three days later, a further wound debridement and full closure were performed.

A transvaginal ultrasound examination and hysteroscopy with dilatation and curettage ruled out endometritis as a cause of ongoing septic shock. No specific organisms were grown on blood or wound cultures so empirical, broad-spectrum antibiotics were administered in consultation with infectious diseases specialists. She remained intubated and mechanically ventilated for a total of nine days, during which time she developed anaemia of critical illness requiring blood transfusions, reactive thrombocytosis and reactive pleural effusions that required drainage.

She was discharged to the surgical ward after 15 days in the ICU, but was readmitted to the ICU twice for recurrence of septic features. Discrete abdominal collections were found on a further CT scan, which were treated conservatively considering the relatively inaccessible locations and associated risks of drainage. A segmental pulmonary embolism occurred despite being on mechanical and medication thromboprophylaxis. She was discharged home after 35 days in the hospital with surgical and obstetric follow up. Her progress has been positive since discharge.

Discussion

The hallmark symptom of OS is marked abdominal distension developing over a short timeframe.8 Often this is associated with abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting. The woman is typically 2–12 days post caesarean section.9 The signs and symptoms may initially mimic paralytic ileus, but bowel sounds are often reported to be higher pitched and hyperactive.10 In addition, patients may still be able to pass small amounts of fecal fluid and flatus. Abdominal pain in OS usually manifests as a dull, crampy sensation with no specific localisation, typical of hollow viscus distension. This may then progress to localise over the right iliac fossa, indicating impending rupture of caecum.11

Patient is usually tachycardic, afebrile (pyrexia might indicate sepsis) and may be hypotensive. Laboratory results may not be helpful in the first instance. In the acute setting, a plain erect abdominal x-ray is most helpful in terms of narrowing down the list of differential diagnosis. This may show a typical picture of large bowel dilatation, especially the caecum with or without pneumoperitoneum. A CT scan can then be requested to confirm the diagnosis of OS and, more importantly, to measure the caecal diameter, which will aid in the management and outcome of patient.

The exact aetiology of OS is still poorly understood; however, the current consensus is that there is an imbalance of sympathetic and parasympathetic innervation of the colon.12 Physiologically, the parasympathetic system increases the motility of the colon while the sympathetic system does the exact opposite. In a large analysis of 400 cases of OS, it was suggested that there is a temporary neuropraxia of the sacral parasympathetic outflow (S2–S4).13 This finding may help to explain OS post caesarean section, but this is yet to be confirmed.

The caecum is the part of the colon with the thinnest wall and largest diameter, which makes it especially vulnerable to perforation. This can be explained by the Law of Laplace, which states that the tension in the wall of a hollow viscus is directly proportional to its radius and intraluminal pressure.14

Management of OS has been classically divided into conservative/medical and surgical. These options are dependent upon the caecal diameter, which in turn is dependent on early recognition of the condition. In general, caecal dilatation of less than 10cm can be managed conservatively, provided there are no signs of perforation.15 This involves the patient being given nil by mouth and the use of nasogastric decompression. Any narcotic analgesics and anti-cholinergic drugs should be stopped.

Medical therapy involves the use of neostigmine, which promotes colon motility by inhibiting acetylcholinesterase. A small trial done in 1999 showed that 50 per cent of patients had an immediate response (within 30 minutes; passing of flatus and reduced abdominal distension) and 73 per cent had a sustained response (lasted over three hours; reduced caecal diameter).16 Neostigmine is given intravenously at 2.5mg over 3–5 minutes. Colonoscopic decompression can be used next if treatment with neostigmine fails. This, however, has a variable success rate (61–78 per cent), with a recurrence rate of 40 per cent.17 18 Any signs of bowel perforation warrant surgical management. This usually entails laparotomy with bowel resection and formation of a stoma.

It is important to maintain a high index of suspicion in the post-caesarean patient presenting with progressive abdominal distension, despite the presence of falsely reassuring bowel sounds and passage of flatus. It cannot be stressed enough the importance of early diagnosis and intervention in preventing a catastrophic outcome to an otherwise young, healthy woman in her reproductive years.

References

- Ogilvie H. Large intestine colic due to sympathetic deprivation: a new clinical syndrome. BMJ. 1948;2:671-3.

- Carpenter S, Holmstorm B. Ogilvie Syndrome. Available from: www.eMedicine.com/med/topic2699.htm.

- Norton-Old KJ, Yuen N, Umstad MP. An Obstetric Perspective On Functional Bowel Obstruction After Caesarean Section: A Case Series. J Clin Gynecol Obstet. 2016;5(1):53-7.

- Kakarla A, Posnett H, Jain A, et al. Review Acute Colonic Pseudo-obstruction After Caesarean Section. The Obstetrician & Gynaecologist. 2006;8:207-13.

- Nanni G, Garbini A, Luchetti P, et al. Ogilvie’s syndrome (acute colonic pseudo-obstruction): review of the literature (October 1948 to March 1980) and report of four additional cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 1982;25:157-66.

- Kakarla A, Posnett H, Ash A. Acute pseudo-obstruction of the colon (Ogilvie’s syndrome) following instrumental vagina delivery: case report. Int J Clin Pract. 2006 Oct;60(10):1303-5.

- Lewis G, Drife J. editors. Why Mothers Die 2000-2002. Confidential Enquiry into Maternal and Child Health. London: RCOG Press; 2004.232-33.

- Carpenter S, Holmstorm B. Ogilvie Syndrome. Available from: www.eMedicine.com/med/topic2699.htm.

- Kakarla A, Posnett H, Jain A, et al. Review Acute Colonic Pseudo-obstruction After Caesarean Section. The Obstetrician & Gynaecologist. 2006;8:207-13.

- Laskin MD, Tessler K, Kives S. Cecal perforation due to paralytic ileus following primary caesarean section. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2009;31(2):167-71.

- Munro A. Large bowel obstruction. In: Wills BW. Paterson-Brown S, editors. Hamilton Bailey’s Emergency Surgery. 13th ed. London: Hodder Arnold; 2000. p.436-9.

- Kakarla A, Posnett H, Jain A, et al. Review Acute Colonic Pseudo-obstruction After Caesarean Section. The Obstetrician & Gynaecologist. 2006;8:207-13.

- Vavek VW, Al-Salti M. Acute pseudo-obstruction of the colon (Ogilvie’s syndrome). An analysis of 400 cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 1986;29:203-10.

- Brock W. Volvulus of the Cecum. West J Surg Obstet Gynecol. 1954;621:12-7.

- Kakarla A, Posnett H, Jain A, et al. Review Acute Colonic Pseudo-obstruction After Caesarean Section. The Obstetrician & Gynaecologist. 2006;8:207-13.

- Ponec RJ, Saunders MD, Kimmey MB. Neostigmine for the treatment of acute colonic pseudo-obstruction. N Eng J Med. 1999;341:137-41.

- Eisen GM, Baron TH, Dominitz JA, et al. Acute colonic pseudo-obstruction. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:789-92.

- Rex DK. Colonoscopy and acute colonic pseudo-obstruction. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 1997;7:499-508.

Leave a Reply