Postpartum haemorrhage (PPH) complicates 18 per cent of births and is the most common maternal morbidity in developed countries. Secondary PPH is defined as excessive vaginal bleeding from 24 hours after delivery, up to six weeks postpartum. It is rare, brief and self-limiting, with the most common cause being retained products of conception.

Uterine arteriovenous malformation (AVM) is a rare cause of PPH, with fewer than 100 cases in current literature. It is potentially life-threatening, as patients can present with profuse bleeding. Uterine AVM is thought to be present in 0.22 per cent of postpartum women, but as not all are symptomatic, many go undiagnosed. While ultrasound is the first-line of investigation, the current gold standard for diagnosis is by angiography.

Management of uterine AVM varies depending on haemodynamic status, degree of bleeding, age of the patient and desire for future fertility. Conservative management by uterine artery embolisation is the preferred treatment, in order to avoid a hysterectomy in women of child-bearing age. Bilateral uterine artery embolisation has a reported 90 per cent success rate in managing uterine AVM.

Case report

The patient is a 22-year-old, G1P1, who was referred to our tertiary facility with a secondary PPH of 500ml at four weeks postpartum. It was the patient’s first pregnancy by spontaneous conception, with no history of previous surgeries. She had a low-risk pregnancy until 39 weeks gestation, when she developed pre-eclampsia. She was induced at 39 weeks and had a normal vaginal delivery one day later. She had a postpartum haemorrhage of 2700ml, which was managed medically. Surgery was not required. Her bleeding settled and she was discharged home.

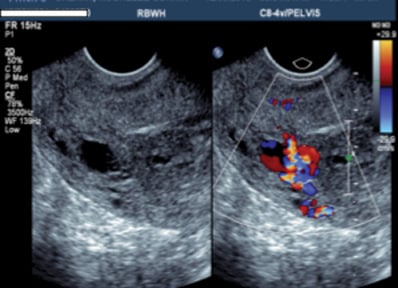

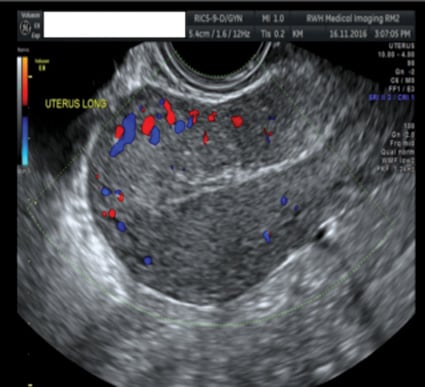

Figure 1. Gray scale ultrasound showing the serpiginous structures within the myometrium, which raised the concern for a uterine AVM.

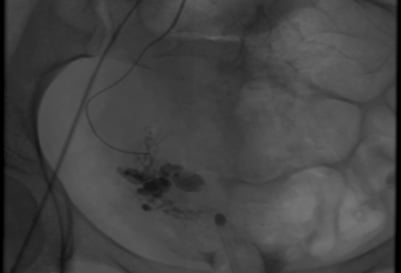

Figure 2. Angiography: Pre R) uterine artery embolisation. Note the serpiginous tangle of vessels.

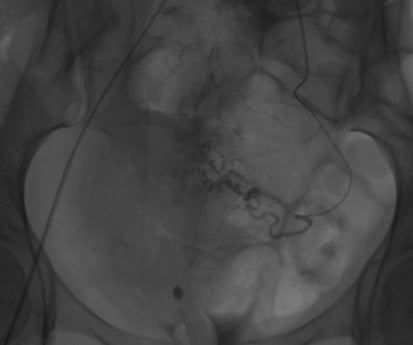

Figure 3. Angiography: Post R) uterine artery embolisation.

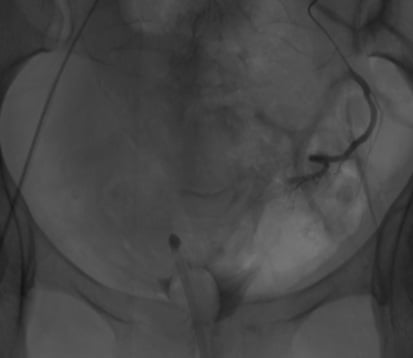

Figure 4. Pre L) uterine artery embolisation.

Figure 5. Post L) uterine artery embolisation.

Figure 6. 6/52 post-bilateral uterine artery embolisation.

Postnatal course

The patient re-presented to hospital four weeks postpartum after losing approximately 500ml of blood at home. Ultrasound showed no retained products, but suggested the possibility of a uterine AVM. She was transferred to our facility for consideration of further management. On arrival, she had stopped bleeding and was observed for 48 hours. The decision was made for conservative treatment, given that she was haemodynamically stable and no longer having blood loss. She was discharged home and advised to return should she have another haemorrhagic event.

The patient re-presented to her previous hospital two days later with another bleed of 500–600ml. She was taken to theatre and had a Foley catheter inserted into the uterus, filled with 40ml normal saline to tamponade the bleeding. Ultrasound, again, showed no retained products of conception, but still suggested a potential uterine AVM. The patient was transferred back to our facility for a uterine artery embolisation. She was haemodynamically stable with haemoglobin of 87g/L on arrival. All other blood test results were unremarkable.

Her ultrasound images were reviewed by our interventional radiology team and a recommendation was made for angiography and bilateral uterine artery embolisation. The procedure was successful and the patient was observed in our facility for another 48 hours post-embolisation, before being discharged home. We reviewed her six weeks post-procedure with a repeat ultrasound. She was well and had no further bleeding. She had one normal menstrual cycle which was not heavy. She has now been discharged from our clinic. For her next pregnancy, we have recommended an early ultrasound and referral to a tertiary centre to monitor for any abnormal placentation.

Discussion

A uterine AVM consists of proliferation of vascular channels, with fistula formation and an admixture of small capillary-like channels. The size of these vessels vary considerably. There are congenital or acquired uterine AVMs and the latter are more common.

Acquired uterine AVMs are associated with conditions, such as multiple pregnancies, miscarriage, previous surgery (for example, dilatation and curettage), termination of pregnancy and caesarean section. None of these are applicable to our case. However, pregnancy appears to play an important role in the pathogenesis of uterine AVM. It is suggested that these malformations may arise when venous sinuses become incorporated in scars within the myometrium, after necrosis of the chorionic villi.

From a clinical perspective, these vascular anomalies most commonly present with abnormal uterine bleeding. Depending on the presentation, some women may be haemodynamically unstable. Torrential bleeding may occur post-uterine curettage, as there is often only a thin layer of endometrium overlying the malformation, which may be disrupted. This would explain the intermittent bleeding pattern. Diagnosis of uterine AVM has been proven difficult and treatment has often been hysterectomy. However, that is not ideal for a woman who would like to preserve her fertility.

There are different modalities available for imaging, but the current gold standard for diagnosis is angiography. While it is considered more invasive than gray-scale ultrasonography, angiography helps to identify the leading ‘feeder’ vessels, where embolisation may be indicated as a conservative treatment option.

Pelvic MRI was another non-invasive investigation considered in this case. However, given the clinical context and after discussion with our interventional radiology team, we made the decision to proceed straight to angiography and bilateral uterine artery embolisation concurrently.

Bilateral uterine artery embolisation has a reported 90 per cent success rate in managing uterine AVM and proved to be an effective treatment option in our case study.

While uterine AVMs are rare, it is an important differential to consider in patients with otherwise unexplained secondary PPH.

Acknowledgements

Dr J Clouston. Interventional Radiologist, Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital, Brisbane, Australia.

Dr D Baartz. Consultant Gynaecologist, Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital, Brisbane, Australia.

References

1. Kelly SM, Belli AM, Campbell S. Arteriovenous malformation of the uterus associated with secondary post-partum haemorrhage. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2003; 21:602-605.

2. O’Brien P, Neyastani A, Buckley AR, Chang SD, Legiehn GM. Uterine arterioveous malformations – from diagnosis to treatment. J Ultrasound Med. 2006; 25:1387-1392.

3. Rufener SL, Adusumilli S, Weadock WJ, Caoili E. Sonography of uterine abnormalities in postpartum and postabortion patients

– a potential pitfall of interpretation. J Ultrasound Med. 2008; 27:343-348.

4. Hashim H, Nawawi O. Uterine arteriovenous malformation. Malays J Med Sci. 2013; 20(2): 76-80.

5. Girija. Arteriovenous malformation of uterine artery: a rare cause of secondary. Postpartum Haemorrhage. Indian Journal of Mednodent and Allied Sciences. 2014; 2:72-74.

6. Mosedale TE, Martin G, Majumdar A. Uterine arteriovenous malformation: A rising cause of postpartum haemorrhage? Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2016; 36:687-689.

Leave a Reply