Throughout history women have sought to control their fertility and abortion has always been a part of this. Written fragments surviving from ancient Egyptian, Greek and Roman times contain many details and prescriptions of plants and herbs that could act as contraceptives or abortifacients. Some of these, such as pennyroyal, continued to be used for hundreds of years until the early 20th century, presumably because, although there may have been serious side effects, they were often successful in bringing about a termination.

Two truths about abortion emerge from this history: women with unintended unwanted pregnancy will seek termination regardless of whether it is legal or acceptable in the society in which they live; and women who cannot obtain safe, legal termination will seek, and often find, unsafe illegal abortion.

The ‘modern’ history of abortion, insofar as it affects Australian women today, began in the middle of the 19th century, in the UK. In 1861, UK Parliament passed the Offences Against the Person Act. Section 58 of this Act decreed that any person ‘who unlawfully uses an instrument to procure the miscarriage of a woman, whether she is with child or not, is guilty of a felony punishable with penal servitude for life.’ There was an exception to the 1861 Act in ‘therapeutic abortion’– justified if the woman’s life was in danger – but the definition of ‘therapeutic’ was unclear and there were virtually no abortions openly performed by registered medical practitioners.

The point of the legislation was partly to protect women from unsafe and unskilled attempts at instrumental abortion, but also to punish them for their ‘immorality’. The Church took an increasingly authoritarian stance on abortion from the 19th century onward, with the strong message that a woman who had demonstrably taken part in sexual intercourse should pay the price by continuing the pregnancy. The legislation failed to achieve the first of these. Women in the UK sought out abortion wherever they could, from providers with few or no skills, and little knowledge of antisepsis. It did, however, provide significant punishment to women. Being clandestine, abortion was a major cause of maternal mortality in the 19th and the first half of the 20th century, and many women who survived did so with chronic ill health.

From 1861 onwards, the harsh measures of the Act meant that prosecutions for abortion providers were relatively common in England. However, in virtually all cases, the defendants were women with little or no medical training, performing terminations for small fees – the so-called ‘backstreet abortionists’. At any one time, around 50 women convicted of the crime of abortion were incarcerated for up to 14 years in London’s Holloway Prison. Their motivation was not necessarily purely financial. One woman said, ‘I knew it was against the law, but I didn’t think it was wrong. Women have to help each other.’

Increasingly, in the early years of the 20th century in the UK, there were calls for reform of law by women (and some men) who were involved in achieving the vote for women and in seeking better reproductive and maternity care. These demands were supported by a small numbers of doctors, including Mr Aleck Bourne, FRCS, consultant gynaecologist at St Mary’s Hospital in London.

In July 1938, Bourne stood in the dock of the Old Bailey court in London, charged under Section 58 of the 1861 Act.1 Bourne was definitely not a ‘backstreet abortionist’, although he shared the altruism of some of those women: he had charged no fee for performing the allegedly criminal procedure. There was the exception to the 1861 Act in ‘therapeutic abortion’ but the definition of ‘therapeutic’ was unclear. Bourne was determined to test the law in court with the intention of defining ‘therapeutic’ abortion and he was prepared to risk conviction to do so.

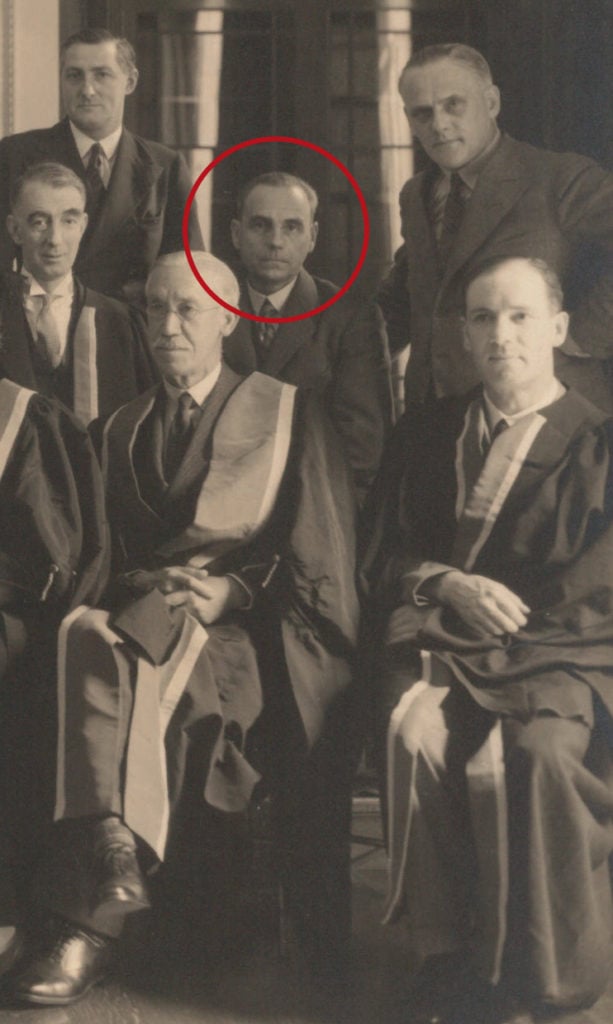

Aleck Bourne (centre) with colleagues from the Council of the British College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, taken in College House, Queen Anne Street, London, in 1934. Image on loan from the RCOG Archives.

The person at the centre of the case was a 14-year-old girl. She had been gang-raped in London’s Whitehall by three Horse Guards, who in June 1938 were convicted and jailed. England’s Attorney-General personally led the prosecution of Bourne. In his opening remarks to the court, he made it clear that he was well-disposed toward the girl. He explained that her parents had taken her to see Dr Joan Malleson, a London general practitioner. Joan Malleson was a woman of liberal views and strong personality. She was an active member of the Birth Control Movement and largely responsible for establishing the original English Family Planning Association. It was Dr Malleson’s opinion, and that of the police surgeon who had seen her following the rape, that ‘curettage’ – surgical abortion – should be allowed to her.

Dr Malleson wrote to Bourne asking if he would be prepared ‘to risk a cause célèbre and undertake the operation.’ Many people, she said, held the view that the best way of correcting the laws in England was to let the medical profession extend the ground for ‘therapeutic abortion’ in suitable cases until the law had become obsolete as far as practice went. She believed that public opinion would be very much in favour of the abortion conceived in a case such as this.

In 1935, Bourne had been referred a similar case, a girl of 15, and after consultation with a colleague he had terminated that pregnancy. He had been criticised by other colleagues and his registrar had left the operating theatre midway through the surgery. This ‘annoyed me,’ he wrote with true British phlegm. ‘I decided that should another similar opportunity come my way I would report what I had done to the police.’ He therefore replied immediately to Joan Malleson’s letter: ‘I have done this before and have not the slightest hesitation in doing it again.’ In early June, the girl was admitted under Bourne’s care to St Mary’s and, on 14 June, he operated ‘with no difficulty and afterwards there were no complications of any kind.’

Bourne was finishing his operating list that evening when he learned that police officers from Scotland Yard were waiting to see him. Chief Inspector Bridger told Bourne that ‘in no circumstances could he countenance the operation on humanitarian grounds.’ Bourne replied crisply that it was not the Inspector’s right to dictate to him what he should or should not do in the best interests of his patients, adding that most medicine was performed on ‘humanitarian grounds’. Since he had already operated on the girl, Bourne said, perhaps the Chief Inspector should arrest him. So in due course, Bourne appeared in the local Magistrates’ Court, where after formal evidence was given he was committed for trial and released on bail of £200.

The Attorney-General prosecuting called no medical witnesses to the trial, while Bourne’s team called senior psychiatrists and gynaecologists to support his defence. The police surgeon told the court his examination showed the result of ‘violence and rape’. The prosecution did not dispute these facts, but based their case on the argument that the abortion had not been needed to preserve the life of the girl. There was no certainty of her death if her pregnancy had continued.

Bourne and his team argued strongly that life did not merely mean the risk of the girl’s death, but encompassed her future physical and mental health. His eminent medical witnesses agreed unanimously that ‘severe mental or nervous breakdown seemed likely to occur if the girl’s pregnancy was not terminated’ and described other similar cases that had been followed by such consequences. Bourne himself stated that he could not draw a line between danger to life and danger to health. ‘If one waited for danger to life, the woman would be past assistance,’ he pointed out. He emphatically included mental with physical health in overall ‘health’ – each kind of health was essential for the other, he said.

Mr Justice Macnaghten then addressed the jury, and it is on this address that doctors charged with procuring abortion elsewhere in English-speaking jurisdictions in following years based their (successful) defences. The judge spoke of the difficulties in individual cases of making the sharp distinction between life and health. He concluded: ‘If the doctor is of the opinion, on reasonable grounds and on adequate knowledge, that the probable consequences of the continuation of the pregnancy would make the woman a physical or mental wreck, then he operates, in that honest belief, for the purpose of preserving the life of the mother.’ The jury took 40 minutes to deliberate on Macnaghten’s remarks and returned a verdict of ‘not guilty’.

I have dwelt at length on Bourne’s case, as the outcome played a significant role in the various cases that from 1969 onwards were brought against Australian doctors, in which these practitioners were charged under Australian state criminal laws worded exactly as the 1861 UK Act (which, interestingly, was superseded in 1967 when the Liberal MP David Steel successfully brought the current Abortion Act to Parliament, legalising abortion and making it widely and safely available in most of the UK). These cases, in all of which the accused doctors were acquitted, acted as the defence for doctors providing abortion in New South Wales, Queensland, Victoria, Tasmania and Western Australia until the end of the 20th century, and continue to do so in New South Wales and Queensland, the other three states having reformed or decriminalised their laws.

The Frank Forster Library currently holds seven copies of Synopsis of Midwifery and Gynaecology by Aleck W Bourne, of which this third edition is the oldest, published in 1925.

Until the late 1960s, women in Australia, as in the UK, mostly accessed ‘backstreet abortionists’, often ending up in public hospitals with sepsis or haemorrhage, a situation vividly described by the prominent pro-choice activist Dr Jo Wainer in her book ‘Lost’.2 There were doctors in most capital cities who, for substantial fees, would provide surgical terminations, but these too, being clandestine procedures, often resulted in complications.

In Melbourne, in 1969, Dr Ken Davidson was prosecuted by police for allegedly performing an abortion and the case was heard by Justice Cliff Menhennitt. Bourne’s case was crucial to Menhennitt’s reasoning about the Davidson case in his address to the jury. Menhennitt ruled that a defence to termination exists if the doctor ‘honestly believes’ on reasonable grounds that the termination is necessary to preserve the woman from serious danger to her life or her physical or mental health. The doctor must also honestly believe that, in the circumstances, the risks of the abortion are in proportion to those of continuing the pregnancy (that is, the termination itself does not seriously threaten the mother’s life). Menhennitt’s favourable directions to the jury led to Dr Davidson’s acquittal. The Menhennitt ruling became the basis on which abortion was safely and openly offered to women in Victoria from 1969 onwards. The first clinic to openly offer abortion in Melbourne, the Fertility Control Clinic, was founded by Dr Bert Wainer in 1972.

In New South Wales, abortion was, in 1969, and is still, in the NSW Crimes Act 1900 (sections 82, 83 and 84) with penalties of up to 10 years imprisonment for the woman, the doctor and anyone who assists. While the Act does specify that abortion is a crime only if it is performed ‘unlawfully’, it does not actually define when abortion would be considered lawful or unlawful.

To help clarify the situation, Judge Levine, in 1971, established a legal precedent similar to Menhennitt’s. In a case against Dr Wald, in which the doctor was acquitted, Levine allowed that an abortion should be considered lawful if the doctor honestly believes on reasonable grounds that ‘the operation was necessary to preserve the woman involved from serious danger to her life or physical or mental health which the continuance of the pregnancy would entail’ and that, in regard to mental health, the doctor may take into account ‘the effects of economic or social stress that may be pertaining to the time’. Levine also specified that two doctors’ opinions are not necessary and that the termination does not have to be performed in a public hospital, opening the way for the appearance of easily accessible and safe clinics in NSW, among the first of which was the Preterm Clinic in central Sydney. Levine’s judgment was followed by the judgement of Justice Michael Kirby, in 1994, that further liberalised the grounds for the performance of abortion in NSW; nevertheless, abortion remains in the criminal legislation.

Similarly, in 1985, Dr Peter Bayliss was charged under Section 224 of the Queensland Criminal Code with performing an abortion at his Greenslopes Clinic in Brisbane. The case was heard in front of a jury, by Justice McGuire. Addressing this jury McGuire stated: ‘In my opinion, Bourne and those cases to which I have referred (Davidson and Wald), which have their genesis in Bourne, substantially represent the law of Queensland. I am of the opinion that Davidson…represents the present law of Queensland, and I interpret Section 224…of the Queensland Criminal Code accordingly.’ In other words, McGuire advised the jury, they must decide if the accused held an honest belief that the abortion was necessary for the preservation of the woman’s physical and/or mental health, and that the risks of the termination itself were relatively small. The jury returned a unanimous verdict of not guilty. This judicial ruling still forms the basis of a defence upon which any 21st century Queensland doctor charged with performing an abortion would depend.

McGuire, in his written judgement, also said: ‘This Ruling serves to illustrate the uncertainty of the present abortion laws of Queensland. It will require more imperative authority to effect changes if changes are thought to be desirable or necessary with a view to amending and clarifying the law.’ At the time of writing, while the Queensland Law Reform Commission is reviewing the 1899 Criminal Code sections, this law remains in place.

The ACT decriminalised abortion in 2000, Victoria in 2008, Tasmania in 2013 and the Northern Territory in 2017. Western Australia made substantial changes to their law in 1998, and, in 1970, South Australia updated 1935 legislation, although some reform is still required in both these states. In New South Wales and Queensland, however, the law has still to emerge from the 19th century, when antibiotics and medical, surgical and anaesthetic procedures used today for abortion did not exist. Hopefully, law in both these states will soon be rewritten, so that women making the decision to terminate a pregnancy and women choosing to continue are regarded equally by the law, and all women’s choices are regarded with respect by their healthcare providers.

Leave a Reply