When we chose a career in O&G we committed to caring for girls and women with pain. Over the last decade, rapid changes in neuroscience have laid to rest the concept that pelvic pain is just in the pelvis. Once any pain has been present for more than three to six months, central sensitisation in the spinal cord and brain will be present. Pain becomes more complex and the spectrum of symptoms will often include anxiety or depression. While pain is part of our working lives, coping with distressed patients may seem overwhelming. This article provides suggestions to enhance and support your management of patients with chronic pain, anxiety and depression.

Streamlining the consultation

Pre-appointment questionnaire

Asking your patient to complete a questionnaire before their appointment provides a history and brief mental health assessment at a glance. Suggested freely available questionnaires include the Pelvic Pain Questionnaire for Girls and Women (www.pelvicpain.org.au) and the DASS-21 questionnaire for depression, anxiety and stress (PDF).

Early pain validation

Negative tests, disappointing past treatments and community misunderstanding may result in a patient feeling fearful that her pain will not be taken seriously. She may spend much of her consultation explaining that her pain is real and severe.

A positive rapport can be established quickly with prompt initial pain validation, for example, ‘Thanks for coming to see me today. I hear you’ve had a really difficult time with pain’. This ensures that she knows you understand her pain is severe. Allowing the woman to speak for the first few minutes, describing her main concerns, guides the consultation to the areas she is most anxious about.

Sentences with two phrases joined by ‘but’ imply that you do not believe the first phrase to be true and are best avoided. For example, ‘Your pain is real, but I think you should see a psychologist’, suggests that you do not believe her pain is real. Joining phrases with ‘and’ is more effective.

Previous sexual assault

While a history of distressing sexual events may be important, not all women will wish to discuss this with you or consider it relevant to their pain.

A questionnaire item with a range of possible answers, such as the one below, allows the woman to decide the focus of her consultation. It is time efficient and demonstrates a readiness to discuss the assault if she wishes to.

Have you experienced distressing sexual events during your life, including sexual assault? Yes/No

I prefer not to answer this question.

I would like to discuss this during my appointment.

I prefer not to discuss this during my appointment.

Motivational interviewing and reflective listening

Prolonged pain may have left your patient emotionally and physically exhausted, with limited energy to take on new treatment options. Building momentum for change is enhanced by ‘reflective listening’ and a psychologist may use this technique. For example, the woman explains: ‘I’ve been on opioids for pain for ten years’. You reply: ‘So, despite using opioids for ten years, you’re saying that it’s not helping your pain?’ She nods. You ask: ‘What do you think would help with this pain?’

This process involves listening and then reflecting back her findings. Patients are more motivated by their own thinking and there is less pressure on the practitioner to come up with solutions for complex issues. When listening reflectively, an opportunity will come to make suggestions. For example, when listening to a description of stabbing pelvic pain:

You: ‘That sounds like pelvic muscle spasm. What do you think would help your muscle spasm?’ Where she doesn’t know, you have the opportunity to suggest options that accord with her own thinking.

Mobilisation

Exercise is the best non-drug treatment for pain, but it is also highly advantageous for mental health conditions. As many women with persistent pelvic pain will have obturator internus muscle spasm, pacing and choosing an exercise that is ‘away from the core’ works best. These may include stretches, a daily walk, or free-flowing dancing styles, such as salsa.

Avoid opioids

The regular use of opioids for pain began with palliative care, where death provides an exit strategy and there is no expectation of a normal life. Unfortunately, regular opioid use increases chronic pain by inducing central pain sensitisation.

Referral to a psychologist

A psychologist offers a series of long consultations and will work with your patient on:

- Education about pain processes and the link to psychology and the brain

- Thinking and behaviour patterns for people with chronic health conditions

- Pacing behaviours to avoid the boom/bust cycle of energy and fatigue

- The management of co-morbid mental health pain conditions to improve their engagement with health services

After years of negative experiences, your patient may be sensitive to the suggestion that psychology could be of benefit. It is important to explain that including a psychologist will not reduce your efforts to manage her pain. Useful phrases might include: ‘Your pain is real and pain is a complex illness. Your brain has a role, your thinking has a role, and therefore psychology has a role in assisting you manage your pain.’

How referral to a psychologist works

Masters of Psychology graduates are eligible for registration as a psychologist. However, a health psychologist has undertaken further training and works within the specific overlap between health and mental illness, often within specific areas such as chronic pain. Effective treatment means finding the right psychologist, as well as the right treatment. Asking your patient to ‘Let me know how it goes’, or enquiring ‘Did it go well?’ provides you with feedback.

A mental health care plan (MHCP), prescribed by a GP, provides ten Medicare-subsidised sessions with a psychologist where your patient has been referred for anxiety or depression. While pain alone is not a current indication for a MHCP, these conditions frequently co-exist. As acknowledging the presence of either anxiety or depression may have implications for her workplace, some women may prefer to pay for consultations privately.

Confidentiality limitations require a psychologist to obtain informed consent prior to divulging any information to a third party. Psychologists place similar importance on this as we place on informed operative consent. Special privilege is provided to the referring doctor, who should expect a progress report after six and ten sessions, and can request earlier feedback if required. If you are not the referring doctor, then the psychologist will need to meet with your patient to obtain their written informed consent before providing you with information. Unless urgent, this may take one to two weeks to obtain, depending on how often your patient attends their psychologist.

Psychology therapies

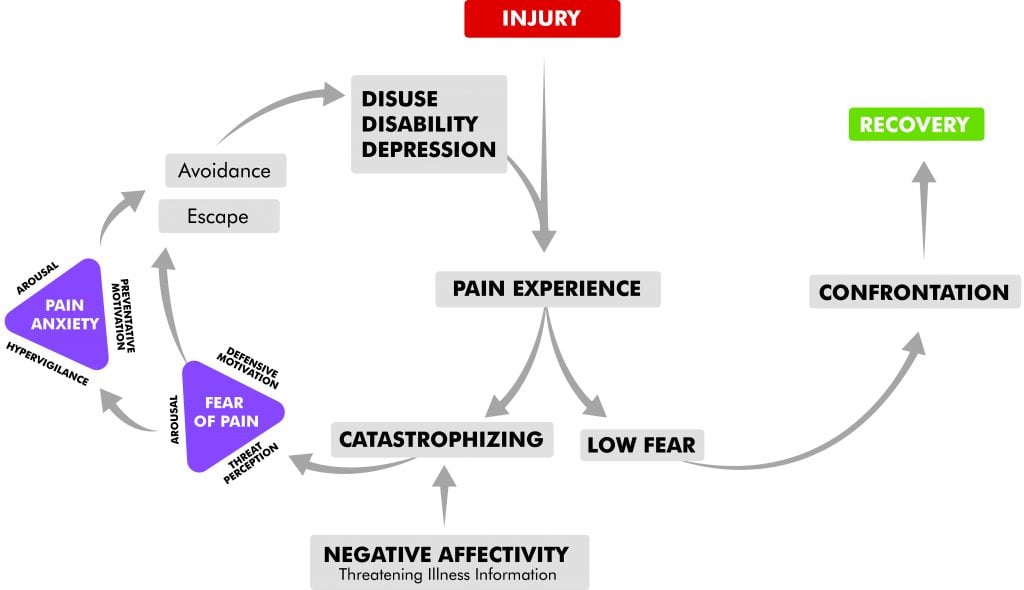

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) works with the fear-avoidance model, where fear and anxiety responses to pain lead to more fear and consequent avoidance of that pain and fear (Figure 1). This is functional and normal for acute pain, but for chronic pain it can lead to more pain, disability, catastrophising and worse mental health outcomes. CBT works by targeting each aspect of this cycle, by providing accurate information, building awareness of this cycle, challenging dysfunctional beliefs and thinking patterns, and adjusting unhelpful behaviours.

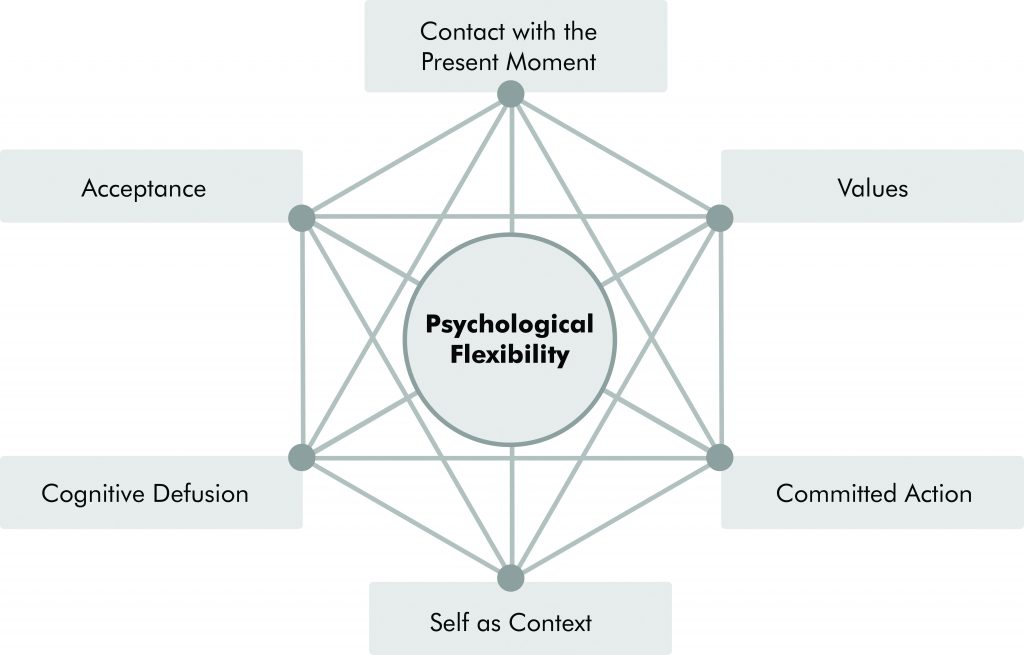

Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) works on increasing each of the six domains (Figure 2) in order to facilitate aspects such as mindfulness, increased pain tolerance, and values-based activities in order to improve functioning.

Pacing is used to breakdown activities, facilitate increased activity levels, reverse pain sensitisation, improve strength and enhance pain management in the long term.

Figure 1. Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT)1

Figure 2. The six domains of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT)2

Online pain and mental health courses for patients

Over the last few years, validated and successful online courses have become available for patients with chronic pain associated with anxiety or depression. These bring together pain education, mental health support, mobilisation and pain self-management techniques. These courses are particularly useful for patients who are unable to attend, afford or access pain psychology services:

- The Pain Course (Macquarie University) is a free online course with five weekly lessons that teaches neuroscience and pain self-management techniques. It is particularly useful for any person with pain associated with anxiety or depression. Patients register at: www.ecentreclinic.org.au.

- Chronic Pain Reboot (St Vincent’s Hospital, Sydney) is a comic-based education and mobilisation course with eight weekly lessons and the option of weekly GP feedback. It costs A$59 for four month’s access and is suitable for any level of mobility or chronic pain. Patients register at: https://thiswayup.org.au/how-we-can-help/courses/chronic-pain.

While improvement in absolute pain scores following completion of these courses may be modest, they have been shown to significantly reduce the impact of pain on patients’ lives.

Medications for central sensitisation

Many of our patients arrive at our care already using a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) medication. A more effective choice, with higher likelihood of pain improvement, would be a serotonin noradrenalin reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) such as duloxetine or venlafaxine. These medications offer the dual benefit of anxiety or depression management via the serotonin receptor and pain management via the noradrenaline receptor.

While duloxetine is usually started with 30mg in the morning (mane) for two weeks, then 60mg mane, young female patients may find starting at a lower dose easier. Starting with a lower dose makes initiating treatment more acceptable. To initiate treatment with a 15mg dose, open a 30mg capsule, discard half the contents and close the capsule.

Amitriptyline is the drug with the lowest number needed to treat (NNT=2.1) of any medication for central sensitisation. A dose of 5–10mg in the early evening can reduce pain, improve sleep, reduce bloating, reduce vulval pain, reduce background headaches and slow the bladder. A dose of 10–25mg may be required for bladder overactivity or further reduction of chronic headache. These doses are ineffective for depression and improved compliance requires an explanation that amitriptyline has been prescribed for pain rather than depression.

Detailed information on prescribing for women with pelvic pain is outlined in the article, Medication management of chronic pelvic pain, available at www.pelvicpain.org.au.

Leave a Reply