Persistent pelvic pain (PPP) has been defined as noncyclical pain of six or more months duration that localises to the anatomic pelvis, anterior abdominal wall at or below the umbilicus, the lumbosacral back or the buttocks, and is of sufficient severity to cause functional disability or lead to medical care.1 The prevalence of PPP is estimated to be 15–27 per cent.2

PPP is a well-recognised, frustrating symptom for both the patient and physician. Due to the variable nature of presentation involving various organ systems, patients often undergo several expensive and unnecessary investigations and surgical procedures. Women with PPP use three times more medications, have four times more gynaecological surgeries, and are five times more likely to undergo hysterectomy than women without PPP.3 Despite these interventions, about 30 per cent of patients continue to experience persistent pain for more than five years.4

Table 1. Other causes of PPP (adapted from ISPOG European Consensus Statement 20155).

| Diseases | Causes and findings |

| Urological | Interstitial cystitis Urethral syndrome Malignant urological disease Bladder function disorders Chronic inflammatory urinary tract Urolithiasis |

| Gastrointestinal | Irritable bowel syndrome Chronic constipation Chronic-inflammatory intestinal diseases Malignant intestinal diseases Stenosis of the small or large intestine Chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction |

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue | Fibromyalgia Myofascial pain, trigger points Chronic back pain Neuralgia/neuropathic pain syndrome Dysfunction of the pelvic floor Scar pain Malignant disease of the musculoskeletal system and of connective tissue Nerve compression syndromes Hernia |

| Psychiatric/psychological disorder | Somatoform disorders Adaptation disorder Schizophrenic, schizotypal and delusional disorders |

PPP has been viewed as a complex neuromuscular-psychosocial disorder sharing the characteristics of chronic regional pain syndrome (such as reflex sympathetic dystrophy) or functional somatic pain syndrome (such as irritable bowel syndrome and nonspecific chronic fatigue).6 Up to 50 per cent of patients with PPP have history of physical, sexual and emotional abuse or trauma and about one third have positive screening results for posttraumatic stress disorder.7

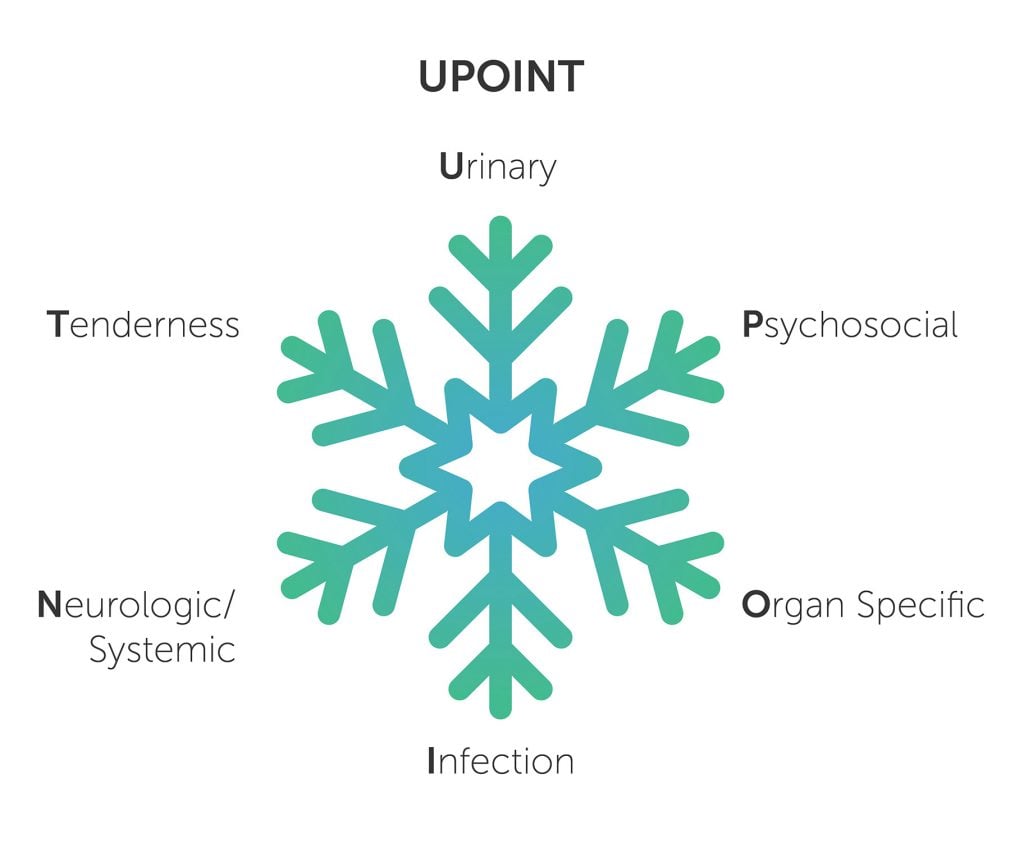

To induce reflection of this multidimensional complexity, Shoskes et al were first to propose a clinical phenotype-based classification system with six domains: urinary, psychological, organ specific, infection, neurological/systemic and tenderness (UPOINT).8 See Figure 1. Several researchers have demonstrated the clinical applicability of UPOINT to prostate and bladder pain syndrome.9

Figure 1. UPOINT is a clinical phenotyping classification system based on the ‘snowflake hypothesis’ for chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Each of the six domains remains open to subcategorisation as new mechanisms and biomarkers are discovered.

Urological domain in PPP

The lower urinary tract consists of the bladder and urethra. The coexistence of symptoms and the common embryologic origin of the structures involved have led to the suggestion of a ‘urogenital pain syndrome,’ including some or all of interstitial cystitis and bladder pain syndrome, vulvodynia, urethral syndrome, coccyodynia, and perineal pain.10 For the bladder pain, patients may complain of increased urinary frequency (day and night), urgency, hypersensitivity, pressure, discomfort, hesitancy, pain with filling, and sensation of incomplete emptying. If the pain is secondary to urethral syndrome, it is perceived usually with voiding and associated dull pressure sensation, radiating towards the perineum and groin.11 Because of the varying nature of presentation and the impact of the condition on women’s lives, treatment needs to be individualised. A multidisciplinary treatment approach including dietary modification, pharmacological agents (such as pentosan polysalphate sodium) and physiotherapy has been recommended. Patients with urethral syndrome secondary to paraurethral gland infection may require treatment with a prolonged course of antibiotics.

Gastrointestinal domain in PPP

The gastrointestinal tract (GI) can be the primary pain generator or may play a critical role in inducing pain symptoms by visceral hypersensitivity syndrome. Patients affected in the GI domain frequently report constipation, diarrhoea and obstructive defecation, abdominal bloating and cramping, pain with defecation, bleeding, discharge, recurrent rectal pain/pressure/burning or aching episodes.12 Anorectal problems may result from haemorrhoids, abscess, fissures, ulcers, levator ani syndrome or chronic proctalgia. Functional bowel disorders, including irritable bowel syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease and malignancy, may present with similar ‘red flag’ symptoms and should be excluded by thorough examination and investigation.

Musculoskeletal domain in PPP

Dysregulation in the musculoskeletal system can be the primary cause of PPP or may be secondary to the patient’s physical adaptation to the primary pathology involving other domains. Musculoskeletal problems may also coexist with other pelvic pathology such as endometriosis.13 Features indicative of a musculoskeletal problem include: point tenderness, abnormal movement and alterations in the muscle (tone, stiffness, tension, spasms, cramping, fasciculation and trigger points). PPP related to musculoskeletal disorders includes myofascial pain syndrome, fibromyalgia, hernia, osteitis pubis, trigger point and sacroiliac joint pain. Researchers have also discovered an association of soft tissue disease, such as fibromyalgia, with other comorbid conditions, such as irritable bowel syndrome, primary dysmenorrhoea and chronic functional headache.14

Physiotherapy addressing pelvic floor and hip muscle is the mainstay of the treatment for this group of patients. Some other measures proven to be helpful include self-directed pelvic floor contraction and relaxation exercises, muscle relaxants and Botox injections.

Neurological domain in PPP

Patients with predominantly neurological domain related pain commonly describe burning, throbbing, electric shock-like sensation, tingling, stinging and/or painful paraesthesia in the pelvis and/or perineal area.15 In persistent pelvic pain, secondary sensitisation of the peripheral or central nervous system can occur, perpetuating the overall pain experience with extending referral areas along with the involvement of another organ system.16

The relevant nerves are sacral, pudendal, thoracolumbar, ilioinguinal, illiohypogastric, genitofemoral or obturator. Local anaesthetic nerve blocks may offer successful treatment for a subgroup of patients, but require repeated injections. In some rare circumstances, surgical decompression of the affected nerve may be an option.

Psychosocial domain in PPP

Psychological factors including depression, anxiety, catastrophising and somatisation are more common among women with PPP compared to control groups.17 Reports of sleep disturbances, helplessness, hopelessness, difficulty concentrating and pain impairing daily enjoyment are frequently encountered. This vulnerable group of women reports more health-related disability, incur higher health costs and have associated sexual dysfunction, particularly dyspareunia, invariably affecting quality of life. Many women also fear to be stigmatised by health professionals who may consider their pain is not real, but rather ‘in her head’.

A formal psychological assessment by valid questionnaires has been recommended to evaluate the extent of psychological comorbidities prior embarking on any specific treatment. Multimodal, personalised approaches involving active communication with primary care providers and a chronic pain team provide the basic framework for comprehensive bio-psychosocial model of holistic and thoughtful care. Most of the patients require extensive psychotherapy (such as cognitive-behavioural therapy), physiotherapy, individual and couples counselling along with pharmacological treatment and social support.

In a nutshell, PPP management requires in-depth understanding of the multidimensional pain mechanism by expert interdisciplinary team members. Following exclusion of any treatable cause, the goal should focus on empowering the patient to resume her normal activity and function by a shared pathway along with the treating team.

References

- J Steege, M Seidhoff. Chronic pelvic pain. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124:616-29.

- A Ahangari. Prevalence of chronic pelvic pain among women: an updated review. Pain Physician. 2014;17(2):e141-7.

- SR Till, S As-Sanie, A Schrepf. Psychology of Chronic Pelvic Pain: Prevalence, Neurobiological Vulnerabilities, and Treatment. Clin Obs and Gyn. 2019;62(1):22-36.

- KT Zondervan, PL Yudkin, et al. Prevalence and incidence of chronic pelvic pain in primary care: evidence from a national general practice database. BJOG. 1999;106(11):1149-55.

- F Siedentopf, P Weijenborg, M Engman, et al. ISPOG European Consensus Statement – chronic pelvic pain in women (short version). J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2015;36(4):161-70.

- D Engeler, AP Baranowski, J. Borovicka, et al. European Association of Urology. Guidelines on Chronic Pelvic Pain. Available from: http://uroweb.org/wp-content/uploads/EAU-Guidelines-Chronic-Pelvic-Pain-2015.pdf.

- D Engeler, AP Baranowski, J. Borovicka, et al. European Association of Urology. Guidelines on Chronic Pelvic Pain. Available from: http://uroweb.org/wp-content/uploads/EAU-Guidelines-Chronic-Pelvic-Pain-2015.pdf.

- JC Nikel, D Shoskes. Phenotypic approach to the management of chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Curr Urol Rep. 2009;10:307-12.

- JC Nikel, D Shoskes, et al. Clinical phenotyping of women with interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome: a key to classification and potentially improved management. J Urol. 2009;182:155-60.

- U Wesselmann. Pain of urogenital origin. Pain Clin Updates. 2000;8(5):1-4.

- N Rana, MJ Drake, et al. The fundamentals of chronic pelvic pain assessment, based on international continence society recommendations. Neurology and Urodynamics. 2018;37:S32-8.

- N Rana, MJ Drake, et al. The fundamentals of chronic pelvic pain assessment, based on international continence society recommendations. Neurology and Urodynamics. 2018;37:S32-8.

- D Raimondo, A Youssef, et al. Pelvic floor muscle dysfunction on 3D/4D transperineal ultrasound in patients with deep infiltrating endometriosis: a pilot study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynaecol. 2017;50:527-32.

- D Engeler, AP Baranowski, J. Borovicka, et al. European Association of Urology. Guidelines on Chronic Pelvic Pain. Available from: http://uroweb.org/wp-content/uploads/EAU-Guidelines-Chronic-Pelvic-Pain-2015.pdf.

- M Haanpää, R Treede. Diagnosis and classification of neuropathic Pain. Pain: Clinical Updates. 2010;18(7):1-6.

- LH Whitaker, J Reid, et al. An exploratory study into objective and reported characteristics of neuropathic pain in women with chronic pelvic pain. PLoS One. 2016;11(4):e0151950.

- CE Martin, E Johnson, et al. Catastrophizing: a predictor of persistent pain among women with endometriosis at 1 year. Hum Reprod. 2011;26:3078-84.

Leave a Reply