‘Never stop learning from your mistakes.’1

More than 20 years ago, in my first few weeks as a registrar, I was asked by a senior colleague to perform a straightforward minor procedure as they were busy. A senior registrar would supervise me. I agreed and went to the theatre to find the patient – whom I had not met or consented – asleep and prepped. My supervising doctor arrived. I started with dilating the cervix and then introducing an instrument into the uterine cavity. On withdrawal of the instrument, I was immediately confused at the yellow and tan tissue that was coming out of the cervical os. It suddenly hit me that I had pulled out a loop of the small bowel.

A general surgeon was called, a midline laparotomy and small bowel resection were performed. The patient was admitted to the ward after what should have been a minor day procedure. Through all of this, I felt incredibly distressed for the patient who I had harmed in a major way and had not even met before it happened. Understandably, I was very concerned about my future career in O&G. Would I ever be able to work again in a field that I loved so much? I went to meet the woman with a senior consultant. I was told to let them do the talking. She didn’t want to see me again.

She eventually went home and I never saw her again, but for a long time I had constant thoughts running through my head about her and her future. How could I have been so stupid? Why had I perforated her uterus? How could I have injured her as I did? Was I the only registrar to have ever done this? Is this the right specialty for me or is this all just too hard? I had trouble sleeping and knew that it was affecting all my interactions with family and friends, but mostly with the patients I was caring for.

I had support from my fellow registrars, but nothing from my consultants or hospital management. It was as if nothing had ever happened. That was, until, the expected complaint letter arrived in my mailbox at work. It sat unopened for several days as I dreaded what judgement was held in its pages. I eventually got the courage to open the letter, which I read with trepidation. The patient wanted to know why she had such a poor outcome, and she wanted an apology. Of course, I was sorry. I was devastated and ashamed that I had caused her injury. The complaint was passed onto management and I was asked to attend a meeting with senior staff and management to address the patient’s concerns. A formal response and apology to the complaint letter was sent. One of my senior consultants tried to console me by saying the letter’s ‘Angina in an Envelope’ would eventually stop.

The complaint was eventually resolved. I continued to work and train as a registrar in a specialty I love. Looking back, the whole incident was magnified due to the swiss-cheese effect of not meeting and consenting the patient first. I still frequently reflect on that incident so early in my career and the permanent effect it had on a woman who I had barely met, the effect that it has had on my practice over the last 20 years, and how very easily it could have ended my career as a gynaecologist.

– Michael Wynn Williams

There is no question that the medical environment has seen rapid positive change over a few short decades, but doctor care still lags behind. Obstetricians and gynaecologists have the highest rates of burnout among doctors, 46 per cent of respondents in the 2018 Medscape Physician Burnout and Depression Survey reported having an issue.2 Physician health and wellbeing need our urgent attention.

It is undeniable that adverse events are a fact of life in our profession. How we deal with these medical complications is a crucial element in protecting our overall wellbeing.

Adverse events are unintended consequences of healthcare management and result in temporary or permanent disability, death or prolonged hospitalisation.3 The incidence of adverse events ranges from 5.7–12.9 per cent, with surgical adverse events being the largest contributor.4 In a 2019 systematic review and meta-analysis, Tanaka et el found the incidence of adverse outcomes in gynaecological hospital admissions to be 10 per cent.5

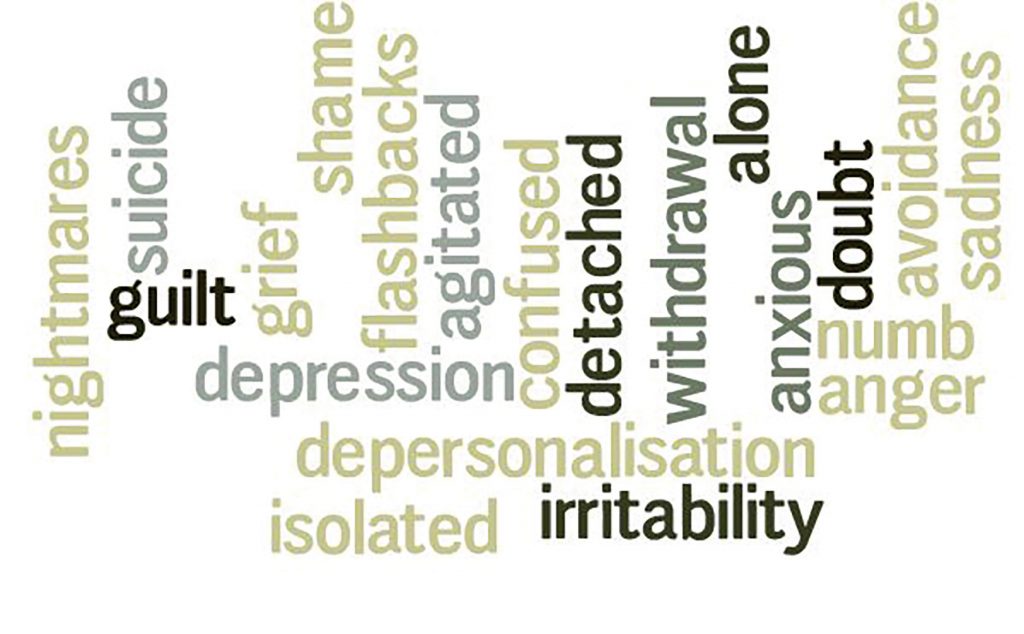

In 2000, Wu introduced the idea of the ‘second victim’ in adverse events. Although patients are always the first victims, the doctors themselves can also be significantly affected. Wu explained what we all know instinctively – that ‘the doctor who makes the mistake needs help too’.6 The psychological and emotional consequences of being involved in adverse events as a doctor have been shown to be similar to those of the patient. They often involve feelings of grief, agitation, worry, guilt and anger.7 8 This can lead to decreased quality of life, burnout, increased use of alcohol and drugs, depression, anxiety, suicidal thoughts and, for some, a decision to change career pathways and even suicide.10

The emotional stress of adverse events has the potential to persist and have significant long-term consequences. In a 2019 systematic review exploring the impacts of patient complications on surgeon wellbeing, one study reported that one-third of doctors met the criteria for acute traumatic stress one month after experiencing a major surgical complication. Participants in another study described emotional distress that impaired their performance for weeks following an adverse event. Some participants reported stopping certain procedures altogether and some chose early retirement.11

The impact of adverse outcomes on you as a doctor

Be aware of the negative impacts that adverse events can have on us personally. There can be long-term negative consequences of adverse events and this awareness can lay the foundation for establishing effective coping strategies.

How do we deal with adverse outcomes and ensure we don’t fall into the trap of unhealthy behaviours?

Looking out for each other

The support from colleagues has been documented to be a critical component of coping with adverse outcomes.6 Healthcare professionals need personal reassurance and professional reaffirmation, which can really only be provided through the support of trusted colleagues. Collegial support can help to avoid the feeling of clinical isolation that often follows an adverse event.12 On the contrary, further harm can occur if unhealthy colleague interactions occur.

Toolbox for helping colleagues

- Make sure you ask, ‘Are you okay? Don’t just assume your colleague is okay

- Don’t forget to talk about how they are feeling, not just the medical facts and decision-making of the case

- Acknowledge the distress of your colleague

- Be a sounding board and listen without judgement

- Share your stories and experiences

- Follow up and check in

The care of patients and their families will always remain the priority in any adverse events; however, the welfare of doctors must also be a top priority. Yielding to the expectation of perfection must be a thing of the past; we must now look carefully and sympathetically at how we develop and nurture a culture of support around adverse outcomes at the individual, collegial and organisational level.

Box 1–3. Toolbox for dealing with adverse outcomes.

Immediate

- Acknowledge and confront the adverse outcome

- Seek advice from a supervisor or clinical director

- Open disclosure with your patient and their family

- Be sure to remain patient centred

- Apologising for the adverse outcome is okay

- Avoidance makes things worse

- Take someone senior with you for support

- Consider reducing or sharing your immediate clinical load

- Contact your indemnity provider

- Not only to advise them of the adverse event, but also to access help and support services

- Write details of the case down and provide a report to your medical indemnity provider

Short term

- If possible, continue to communicate with the patient and their family

- Acknowledge and be aware of the effect an adverse event can have on you

- What thoughts and feelings are you having?

- Debrief with trusted colleagues

- Research has identified that the ability to cope with errors may be dependent on appropriate reassurance by colleagues and supervisors.13

- Lean into your support systems – friends, family and peers

- Self-care

- Exercise, meditation, mindfulness, stress management

- Apps for mindfulness, meditation

- Don’t let fear stop you from accessing help

- Talk to your GP

- Talk to your psychologist, or get one

- Beyond blue: 1300 22 4636

- Lifeline: 13 11 14

- Headspace: 1800 650 890

- Services and support from your medical indemnity provider

- Doctors Health Service: www.drs4drs.com.au

- State-based doctors health services

- Think about the hours you’re doing and upcoming cases you have

- Do you need time off?

- Address your feelings of self-doubt

- Do you need a mentor with you in your upcoming operating list to provide extra support during this time?

Moving forward – long term

- Continue your self-care

- Look out for burnout and long-term effects

- Examine and grow from the experience

- Not just through a focus on the medical facts, but through acknowledgement of the emotional effect the event caused

- Read

- Every Doctor by Leanne Rowe and Michael Kidd

- Complications: A Surgeons Notes on an Imperfect Science by Atul Gawande

- Avant: www.avant.org.au/member-benefits/doctors-health-and-wellbeing/healthy-knowledge-and-career/understanding-the-legal-process/dealing-with-adverse-events/

- MIPS: www.mips.com.au/education/cpd-resources/adverse-outcomes

- Medically Induced Trauma Support Services: www.mitsstools.org

- MITSS Annotated Bibliography: Impact of Adverse Events on Caregivers available online at: www.mitsstools.org/uploads/3/7/7/6/3776466/annotated_bibliography_-_impact_of_adverse_events_on_caregivers_update_0312.pdf

- Watch

- A notification was made about me: A Practitioner’s Experience: www.youtube.com/watch?v=0N5zfLfHiwk

“If there was one thing I could do differently…I would go and talk to someone right at the beginning, because then I would have known I wasn’t alone and that would have really helped the process.”

- A notification was made about me: A Practitioner’s Experience: www.youtube.com/watch?v=0N5zfLfHiwk

- Attend workshops

- Legal ramifications – ‘Angina in an Envelope’

- Don’t put off or ignore legal action

- Moving on

- Be an advocate – make changes at the individual level and within your organisation

- Examine your practice and make changes if needed

- Consider joining or starting a peer support network

- Consider having clinical supervision http://clinicalsupervision.org.au/clinical-supervision/

References

- H Batjer, A Aoun, R Rahme, B Bendok. Overcoming a Bad Outcome: Thoughts from a Colleague. Clinical Neurosurgery. 2012;59:34-43.

- S Robson, R Cukierman. Burnout, mental health and ‘wellness’ in obstetricians and gynaecologist: Why these issues should matter to our patients – and our profession. ANZJOG. 2019;59:331-4.

- K Tanaka, L Eriksson, R Asher, A Obermair. Incidence of adverse events, preventability and mortality in gynaecological hospital admissions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. ANZJOG. 2019;59:195-200.

- K Tanaka, L Eriksson, R Asher, A Obermair. Incidence of adverse events, preventability and mortality in gynaecological hospital admissions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. ANZJOG. 2019;59:195-200.

- K Tanaka, L Eriksson, R Asher, A Obermair. Incidence of adverse events, preventability and mortality in gynaecological hospital admissions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. ANZJOG. 2019;59:195-200.

- A Wu. Medical error: the second victim. The doctor who makes the mistake needs help too. BMJ. 2000;320:726-7.

- A Wu, R Steckelberg. Medical error, incident investigation and the second victim: doing better but feeling worse. BMJ. 2012;21(4):267-70.

- A Srinivasa, J Gurney, J Koea. Potential consequences of Patient Complications for Surgeon Well-being: a systematic review. JAMA. 2019;154(5):451-7.

- K Turner, C Johnson, K Thomas, et al. The impact of complications and errors on surgeons. Bulletin of The Royal College of Surgeons of England. 2016;98(9):404-7.[/note 9S Ullstrom, M Sachs, J Hansson, et al. Suffering in silence: a qualitative study of second victims of adverse events. BMJ. 2014;23:325-31.

- A Srinivasa, J Gurney, J Koea. Potential consequences of Patient Complications for Surgeon Well-being: a systematic review. JAMA. 2019;154(5):451-7.

- A Srinivasa, J Gurney, J Koea. Potential consequences of Patient Complications for Surgeon Well-being: a systematic review. JAMA. 2019;154(5):451-7.

- A Srinivasa, J Gurney, J Koea. Potential consequences of Patient Complications for Surgeon Well-being: a systematic review. JAMA. 2019;154(5):451-7.

Leave a Reply