Ovarian cysts are a common cause for presentation to emergency departments and gynaecology clinics. Up to 10% of women will have surgery during their lifetime for the presence of an ovarian mass.1 The majority of benign ovarian cystectomies can be performed laparoscopically. Basic investigations are completed to stratify risk of ovarian malignancy. These will include a transvaginal ultrasound scan and tumour markers such as Ca125, HE4 and LDH, α-FP and HCG in women under age 40 to rule out germ-cell tumour.2 CEA and Ca19.9 are also commonly requested; however, their clinical value is less clear.3 If there are concerns of malignancy, a gynaecological oncologist should be consulted.

The aims of a laparoscopic ovarian cystectomy are to have minimal blood loss, to perform efficient surgery and to preserve ovarian tissue. It is important to keep the cyst intact to avoid inadvertent spread of undiagnosed malignancy and, in the case of a dermoid cyst, to avoid chemical peritonitis. Endometriomas are an exception and can be ruptured.

Surgical Consent

There are several risks that are specific to performing an ovarian cystectomy that should be discussed with the woman prior to her procedure:

- Risk of oophorectomy

- Risk of spread of undiagnosed malignancy

- Risk of ongoing pain if pain is a primary symptom

- Risk of recurrence of ovarian cysts

Procedure

- Patient is placed in lithotomy position. Routine skin preparation using alcoholic chlorhexidine for skin and aqueous povidone-iodine for vagina and vulva.

- A uterine manipulator is placed.

- Pneumoperitoneum is achieved by the surgeon’s preferred method of entry.

- A 5 mm port is inserted on the patient’s left side. The port is placed 1 cm lateral to the surface landmark of McBurney’s point – one third of the way between the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) and umbilicus. This is done to avoid the inferior epigastric vessels running along the anterior abdominal wall. Port sites may vary depending on size of the cyst, previous surgeries and surgeon preference.

Figure 1. An abdominal survey is performed starting in the right and left upper quadrants looking at the liver and diaphragm.

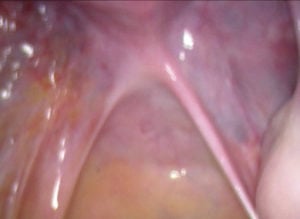

Figures 2 and 3. Both fallopian tubes and ovaries, as well as bilateral ovarian fossae, pouch of Douglas and the bladder peritoneum are inspected. The appendix is also visualised to rule out any pathology and potential cause of abdominal pain. Pictures are taken documenting each anatomical area.

- Two further 5 mm ports are placed – one on the right side and the other in the high-suprapubic position.

Figure 4. If there are any concerns regarding malignancy, peritoneal washing should be performed.

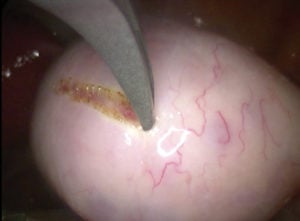

Figure 5. The ovarian cyst is scored using monopolar scissors or hook at a setting of 30–50W of pure cut. Incision is made on the thinnest part of the cyst. Avoid making the incision close to the fallopian tube or fimbrial end. Short bursts of energy are used. It is important not to inadvertently cut through the cyst wall.

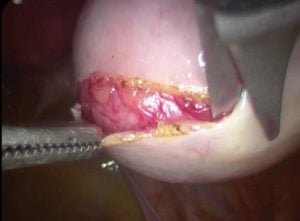

Figures 6 and 7. Plane between the ovarian capsule and cyst wall is developed using a mix of blunt and sharp dissection.

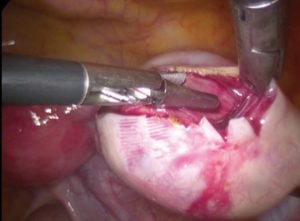

Figure 8. It is important to keep your instruments close to each other. The back of the scissors provides a useful dissection tool. Ensuring the scissors are facing away from the cyst minimises the risk of inadvertent rupture. Slowly work your way around the entire cyst.

- Particularly when dealing with a large and heavy cyst (such as a dermoid cyst), holding the body of the ovary above the cyst allows gravity and the weight of the cyst to help with the dissection.

- Once the cyst has been detached, the ovary can be repaired. Preference is to use a monofilament suture, such as Monocryl®. It is important to include the base of the ovary to achieve haemostasis. Alternatively, haemostasis can be achieved with bipolar energy or with haemostatic agents such as Surgicel®. Haemostasis by bipolar energy appears to have the greatest reduction in ovarian reserve.4

- Check haemostasis. Consider use of adhesion barriers – although evidence is limited.5 Remove ports under vision and close skin wounds.

Figure 9. Suturing the ovary has the added benefit of reducing the likelihood of the ovary adhering to the pelvic side wall.

Figure 10. Cyst is removed using a specimen bag. Pictured is a small Espinar E-Sac®. Other popular alternatives include the Endocatch®.

Deviations from routine practice

- Ovarian cysts in pregnancy: procedure should be performed by an advanced laparoscopic surgeon. Procedure is best performed in early second trimester; however, timing of surgery will also depend on symptoms.

- With increasing age, and if there are any concerns regarding risk of malignancy, consider performing a laparoscopic oophorectomy over a cystectomy.

- Extremely large ovarian cysts: consider obtaining pneumoperitoneum at Palmer’s point.

Effect of cystectomy on ovarian reserve

- Ovarian cystectomies performed for endometriomas have greatest reduction in ovarian reserve, as measured by serum AMH levels.6

- Excessive diathermy appears to be more detrimental. 7 8

Pro Tips

- When dissecting the cyst from the ovary, keep instruments close to each other

- Point scissors away from the cyst

- Include base of the ovary when suturing to close dead space and achieve haemostasis

All pictures courtesy of Dr Michael Wynn-Williams.

References

- Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Management of Suspected Ovarian Masses in Premenopausal Women. Green-top Guideline No. 62. London: RCOG, 2011.

- Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Management of Suspected Ovarian Masses in Premenopausal Women. Green-top Guideline No. 62. London: RCOG, 2011.

- Yeoh M. Investigation and management of an ovarian mass. Aust Fam Physician. 2015;44(1-2):48-52.

- Ata B, Turkgeldi E, Seyhan A, et al. Effect of hemostatic method on ovarian reserve following laparoscopic endometrioma excision; comparison of suture, hemostatic sealant, and bipolar dessication. A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2015;22:363-72.

- Hindocha A, Beere L, Dias S, et al. Adhesion prevention agents for gynaecological surgery: an overview of Cochrane reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;1:CD011254.

- Shah DK, Mejia RB, Lebovic DI. Effect of surgery for endometrioma on ovarian function. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21(2):203-9.

- Ata B, Turkgeldi E, Seyhan A, et al. Effect of hemostatic method on ovarian reserve following laparoscopic endometrioma excision; comparison of suture, hemostatic sealant, and bipolar dessication. A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2015;22:363-72.

- Peters A, Rindos NB, Lee T. Hemostasis during ovarian cystectomy: Systematic review of the impact of suturing versus surgical energy on ovarian function. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2017;24:235-46.

Awesome pictures with explanations attached. Succinct and straight to the point. Thank you so much.

It’s a very clear and simple account of the procedure.