Most physicians deeply value their health. It is a privileged position to walk with patients, helping them manage their health issues. Few doctors would argue that self-care was not important. Many doctors, though, struggle to integrate self-care into their routines. At times of transition (work, family or other life changes) self-care practices can be disrupted. With the focus on the COVID-19 pandemic, doctors’ wellbeing has come sharply into focus.

Confronted with an uncertain future, with the health system central to unfolding events, doctors have found themselves personally and professionally challenged to consider their ‘framework for self-care’.

It is reasonable to step through some of the emerging concerns for doctors related to COVID-19. On the personal front, doctors worry about the health of their family members. They are concerned that their exposure at work will increase their families’ risk. At home, doctors have become the resource for family and friends who seek clarity about what they should be doing. Education of children and care of vulnerable older family members, not to mention increased complexities of shopping, add to the personal issues faced.

In clinical practice, doctors face constant changes:

- Changes to their practice with the introduction of telehealth.

- Changes to their healthcare teams as members are seconded to work elsewhere, while vulnerable staff now work in different roles.

- Apprehension regarding the availability of PPE.

- Clinical care is altered to reduce exposure for both pregnant patients and pregnant doctors.

- Administrative tasks such as updating websites and sourcing clinic supplies are more pressured with extra decisions each day.

COVID-19 has ‘unmasked’ the substantial intersect between the personal and professional lives of doctors.

Beyond the illness itself, financial concerns require attention as professional and personal investment decisions are reviewed. Many doctors have confronted overt discrimination that adds further burden. These issues impact on wellbeing.

Large volumes of information (clinical information, daily statistics, hospital procedures and government announcements) are absorbed and integrated into changes in personal and clinical routines.

Doctors generally dismiss their personal vulnerabilities related to age and previous illness, but this is no longer possible. Reflection upon personal risk factors while working at the coalface can be confronting. Beyond the risk of infection, doctors are also exposed to their patients’ anxieties and their healthcare team’s worries. These can magnify personal concerns. While the frustrations related to decisions by healthcare hierarchy may be tolerated, it is more difficult to understand when close colleagues make very different decisions. Differences can be confronting. Feelings inevitably complicate our decisions and responses. Simply normalising feelings of anxiety, guilt, grief and trauma can be helpful.1 The capacity to think through the multitude of issues can be (frustratingly) slower when there is so much using up our ‘bandwidth’.2 There will be many stages in this marathon that lies before us.3

These self-care messages resonate strongly with the self-care messaging that has been a part of the doctors’ health education for many decades. Doctors need to address their self-care if they are to deliver quality care to their patients.4 Physical and mental health are vital aspects of self-care that remain intertwined. It is rare for doctors across the nation and across the specialties to be facing a crisis together as with the COVID-19 pandemic. However, doctors regularly face difficult times; the traumas of a difficult case that can be heart-wrenching, medicolegal issues, personal issues or medical issues. Practicing self-care enables resilience in these situations.

In acknowledging that self-care is important, it is a perfect time to reflect further: What is self-care, and why has the medical profession struggled to engage with self-care?

What is self-care?

Doctors are health literate with more than a basic knowledge of self-care.5 Clinics are spent providing patients with lifestyle advice on the importance of a healthy diet and exercise while avoiding smoking, illicit drugs and excess alcohol. Lifestyle factors are intimately connected with so many of health issues – contraceptive choices, subfertility, gestational diabetes, endometrial carcinoma. Doctors are reinforcing these self-care messages every day.

Doctors are discerning when scrutinising the lay messages, which include, how to maintain a healthy diet,6 how much exercise is enough7 and the importance of adequate sleep.8 Each of these is inextricably linked to our mental health. Improved diet,9 exercise10 and sleep all enhance our mental health. Specific strategies for addressing our mental health go well beyond mindfulness sessions. Having a range of strategies and understanding the purpose of each of these, what works and when these strategies are best applied is key to enabling mental wellbeing. Key digital resources have been curated by ANZCA in the Long Lives, Healthy Workplaces document, including mental wellbeing resources.11

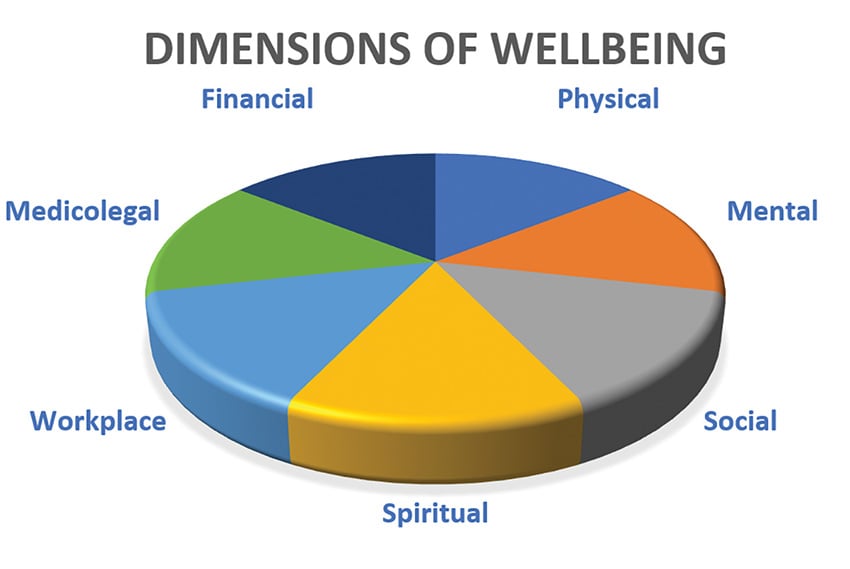

A framework of ‘dimensions of wellbeing’ can assist in reflecting on personal wellbeing. Though these dimensions may vary, seven are commonly used for doctors (Figure 1). While other dimensions such as environmental or emotional may be added or exchanged, such debates distract from the key message that wellbeing is multidimensional. Each of these dimensions need attention. At different times in life, the strategies we use to address one or more dimensions may need to change. Proactive engagement with a framework enables self-reflection to help identify and address problem areas.

Why has the medical profession struggled to engage with self-care?

A lack of knowledge cannot explain why doctors fail to practice self-care themselves. While it is often assumed that disinterest in self-care is simply an attitude adopted when donning the ‘mantle of the white coat’, the reasons are more complex than simple arrogance. It is useful to explore why the discourse of self-care remains fraught. Firstly, the representations of wellness in the literature rarely gel with the lived experience of medicine. Wheels of wellness (Figure 1) with evenly spaced segments are almost confronting. By making wellbeing look ‘easy’ and ‘neat’, such representations contrast starkly with the personal experience of doctors and the lives witnessed when caring for patients. Similarly, the concept of ‘work-life balance’ can seem unattainable when life and work remain inextricably enmeshed with long hours of work, and the patient remains the immediate priority. This apparent cognitive dissonance makes it easy to conclude that the message does not apply, rather than seek an adaptive solution.

Figure 1. The seven dimensions of wellbeing commonly used for doctors.

Again, much of the commentary in the doctors’ health literature insists that doctors do not look after themselves. Yet, doctors do value their health and there is good evidence that doctors benefit from their health literacy.12 Few doctors smoke and many find time for physical activity including skiing, bike riding and surfing. Doctors have a relatively low standard mortality rate when compared to the community. It can be difficult to engage with a message that appears to lack authenticity.

Messages of self-care need to be packaged in a way that enables physicians to incorporate such messages into their daily routines, while acknowledging the difficulties that doctors experience. Research demonstrating why self-care is important for doctor and patient can also help. Breaking for lunch improves the physician’s cognitive function.13

One self-care message is that all doctors should have their own GP. While the number of doctors who say that they have their own GP has increased, many doctors do not attend their GP regularly. Having a relationship with a GP is key to enabling health access, not just ‘having a GP’.14

Doctors record higher stress responses on surveys but are often very aware of their mental health issues. The key issue is access to care. Health access is complicated by concerns of confidentiality, embarrassment and the impact on training and future insurance. While doctors should have positive strategies for managing their day-to-day mental health, such strategies can never be enough for every situation. Increasing doctors’ understanding of safe pathways to care will help to remove barriers and reduce poor help-seeking behaviours.

Stepping forward, doctors do need to address their personal self-care as individuals; however, self-care is more complex than a checklist or wellbeing framework. It takes engagement to be effective. Enabling doctors to hear the current messages of self-care may help them successfully navigate sustainable, lifelong self-care solutions.

Importantly, there are many systemic barriers that also affect self-care. These barriers exist at the healthcare team level and within the broader health system.15 Progressing doctors’ wellness requires an understanding of how these different levels (individual, team and systems) intersect. Hospitals and colleges need to work together to enable sustainable wellness solutions. Doctors’ health can no longer be visualised as an ‘add on’. Their wellness is central to patient care.

Compassion is a key element at each of these levels: self-compassion, compassion for peers and compassion fostered within the system.16 Senior doctors should use their authority and capacity for engagement to enable systemic change.17 Junior doctors benefit greatly when their seniors support them.18Forbes MP, Iyengar S, Kay M. Barriers to the psychological well-being of Australian junior doctors: a qualitative analysis. BMJ Open. 2019;9(6):e027558.[/note Being well-versed in the doctors’ health literature helps enable such change.

The current health system disruptors provide an opportunity for doctors’ wellness to be effectively integrated into both public and private health systems. Doctors do look after themselves, but we can do much better when we work together.

References

- Walker C, Gerada C. Extraordinary times: coping psychologically through the impact of covid-19. BMJ Opinion. March 2020. Available from: https://blogs.bmj.com/bmj/2020/03/31/extraordinary-times-coping-psychologically-through-the-impact-of-covid-19/

- Highfield J. Advice for sustaining staff wellbeing in critical care during and beyond COVID-19. March 2020. Available from: https://www.ics.ac.uk/ICS/Education/Wellbeing/ICS/Wellbeing.aspx?hkey=92348f51-a875-4d87-8ae4-245707878a5c

- Stuchbery M. Minding Health Care workers. Psychological responses of health care workers during the Covid pandemic. March 2020. Available from: https://dhasq.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Minding-healthcare-workers-1.pdf

- Wallace JE, Lemaire JB, Ghali WA. Physician wellness: a missing quality indicator. Lancet. 2009;374(9702):1714-21.

- Department of Health. Head to Health. Australian Government. Canberra. Available from: https://headtohealth.gov.au/

- National Health. Eat for Health. Australian Government. Canberra. 2013. Available from: www.eatforhealth.gov.au/guidelines

- Department of Health. Australia’s Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour Guidelines. Australian Government. Canberra. Available from: www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/fs-18-64years

- Farquhar M. Fifteen-minute consultation: problems in the healthy paediatrician-managing the effects of shift work on your health. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 2017;102(3):127-32.

- Berk M, Jacka FN. Diet and Depression-From Confirmation to Implementation. JAMA. 2019;321(9):842-3.

- Kvam S, Kleppe CL, Nordhus IH, Hovland A. Exercise as a treatment for depression: A meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2016;202:67-86.

- Welfare of Anaesthetists, Everymind. Long Lives Healthy Workplaces. Australian Society of Anaesthetists. 2019. Available from: https://asa.org.au/welfare-of-anaesthetists/

- Kay M, Mitchell G, Del Mar C. Doctors do not adequately look after their own physical health. MJA. 2004;181(7):368-70.

- Kay M, Mitchell G, Clavarino A. What doctors want? A consultation method when the patient is a doctor. Australian Journal of Primary Health. 2010;16(1):52-9.

- Kay M, Mitchell G, Clavarino A. What doctors want? A consultation method when the patient is a doctor. Australian Journal of Primary Health. 2010;16(1):52-9.

- Queensland Health. Health and wellbeing of the workforce- a statement of principles and actions. May 2019. Available from: https://clinicalexcellence.qld.gov.au/priority-areas/clinician-engagement/queensland-clinical-senate/meetings/health-wellbeing-workforce

- Francis R. Report of the Mid Staffordshire NHS foundation trust public inquiry: Executive summary. UK: The Stationery Office. Freshwater. 2013.

- Robson S. Learn from me. MJA Insight. 2019. Available from: https://insightplus.mja.com.au/2019/28/learn-from-me-speak-out-seek-help-get-treatment/

Leave a Reply