It is hard to imagine writing anything right now that does not relate directly to the COVID-19 pandemic. I welcomed the invitation to write about how doctors look after themselves, particularly those in an emotionally and physically demanding craft like obstetrics and gynaecology. I intended to reflect broadly on my personal involvement in lobbying the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) Health Council to change the mandatory reporting requirements in the Health Practitioner Regulation National Law (National Law), and my contribution to amending the World Medical Association’s Declaration of Geneva. The changes to society and medical practice created by the pandemic further emphasise the issues at play in doctors’ health, and how they affect the care we provide our patients.

The mandatory reporting provisions in the National Law present a major impediment to doctors taking care of themselves.

The National Law initially covered 14 health practitioner groups registered with the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (AHPRA). The National Registration and Accreditation Scheme commenced in Australia on 1 July 2010 in all jurisdictions except Western Australia (WA). The Australian Medical Association in WA successfully lobbied then Health Minister Dr Kim Hames to allow an exemption from mandatory reporting by treating doctors.

The WA Parliament accepted the medical profession’s arguments on this issue. Consequently, in that single jurisdiction, there is an explicit exemption from mandatory reporting for treating doctors. WA joined the national scheme on 18 October 2010, with that major amendment in place.

The AMA, during my time as President (2016–18) and beyond, has called for changes to the reporting scheme so that doctors from the other seven states and territories are not prevented from seeking medical treatment.

Doctors are also patients, and at the very least should have equal rights to their own patients in access to medical care.

The unintended consequences from the operation of the current law are far reaching, with doctors and their families suffering and, ultimately, the existence of a health system that is less safe for patients.

Doctors and other health practitioners have the highest suicide rate in Australia’s white-collar workforce, according to data from the National Coronial Information System. In the four-year period of 2011–14, there were 153 health professionals who died as a result of suicide.

Medical practice is stressful and demanding. Doctors are at greater risk of mental illness, of stress-related problems, and more susceptible to substance abuse.

A study of over 12,000 doctors undertaken by Beyond Blue in 2013, revealed that one of the most common barriers to seeking treatment for a mental health condition was concerns about the impact of it on their registration (34%).

The report highlighted the fact that 52% said a fear of lack of confidentiality and privacy was a barrier to treatment – an issue closely related to the fear surrounding mandatory reporting.

There is no evidence to suggest diminished patient safety in WA. In fact, healthy doctors are better placed to help patients. The issues surrounding mandatory reporting have consistently been raised by doctors as a significant barrier to seeking help at an early stage of their illness.

The mandatory reporting requirements for doctors has a two-fold effect: some will not seek treatment at all, and those who do seek treatment may not divulge all the necessary information to receive appropriate care.

Doctors Health Advisory Services reported a significant fall in the level of contact from medical practitioners following the introduction of the mandatory reporting regime. There is anecdotal evidence to suggest that some practitioners have travelled to WA to seek care, safe in the knowledge that they do not have to worry about a mandatory notification by their treating doctor.

The current mandatory reporting provisions, in practice, have commonly been interpreted as requiring a doctor who is treating another doctor who they believe to be in some way impaired, to report that doctor to AHPRA.

Further, the wording of the National Law has been interpreted to provide a very low threshold as to when a notification must be made by the treating practitioner. This is because treating doctors, naturally, seek to limit their risk.

It is critical that every health practitioner can have the confidence to access medical care in a timely way so that health conditions are diagnosed and treated early. Confidentiality is fundamental to the doctor-patient relationship, including cases where the patient is a health practitioner. It is critical that if a health practitioner seeks treatment, that they can have an open discussion about their symptoms so they can be properly diagnosed and treated. This is the only way to avoid the impairment issues that may put patients at risk of harm.

The AMA consistently argued that this situation far outweighs the risks posed by an exemption for treating practitioners from mandatory reporting.

The design of the National Law was to protect the public from unsafe doctors. No government has produced evidence to demonstrate that harm to patients could have been prevented if a health practitioner’s treating doctor had reported them to the regulator. The reality is that most health practitioners become aware of risk of harm to patients by another practitioner while working with them.

The WA model does not in any way alter a doctor’s ethical and professional responsibilities to report a colleague who may be placing the public at risk.

The introduction of the exemption did not reduce the rate of mandatory reporting in WA, indeed the opposite; 92% of mandatory reports were made by colleagues and employers.

AMA members at the 2017 National Conference unanimously passed a motion calling for the urgent removal of mandatory reporting laws across the country, reflecting the strength of the concern within the profession. We recommended adoption of the WA model nationwide to remove inconsistency around the rules for treating doctors.

I recall the day I addressed the state and territory health ministers very well. The failure of the COAG Health Council to act on the AMA’s advice at that time means that we still have a situation where doctors may avoid seeking care. By extension, this raises the risk of harm to patients when their doctor is impaired. A great opportunity to act was squandered.

A suggested compromise was to adopt the WA model, but maintain a mandatory requirement to report sexual misconduct. The amendments made to the legislation in Queensland seek to have the treating practitioner try to make a judgement about ‘future risk’.

Again, it is the uncertainty that has doctors fearful of accessing the basic healthcare they deserve. There is much work still to do on this front.

There is little that cause doctors greater stress than medico-legal matters. Being involved in a civil negligence claim is bad enough. Complaints to the Medical Board and AHPRA, with sanctions including loss of registration, are a source of great anxiety. Medical indemnity providers are important sources of advice and practical support. MDA National’s ‘Doctors for Doctors Program’ is a confidential peer support service for members during a medico-legal matter. Doctors who provide this service are exempt from mandatory reporting obligations, so members can share their concerns freely with a peer who understands their profession and the personal impact of facing a medico-legal matter.

One of the highlights of my term as AMA President was election to the Medical Ethics Committee of the World Medical Association. At the 68th WMA General Assembly in Chicago, we approved only the fifth amendment to the Declaration of Geneva. Dedication to the service of humanity, maintaining the utmost respect for human life and maintaining the health and wellbeing of patients as the primary consideration remain at the centre of the modern physician’s oath.

However, a new line further strengthens this important document:

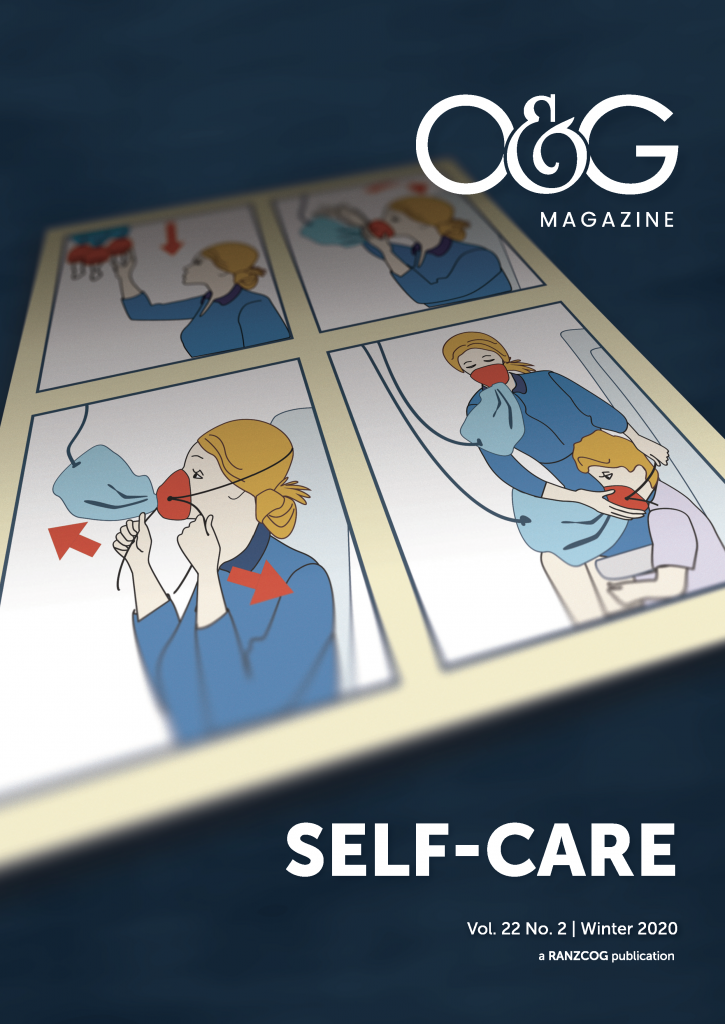

Thus, for the first time, self-care is part of ethical medical practice and within the oath that unites medical practitioners from every corner of the world.

As we consider the evolving COVID-19 pandemic, another threat that permits no ‘consideration of age, disease or disability, creed, ethnic origin, gender, nationality, political affiliation, race, sexual orientation, social standing or any other factor’2 in its impact, it is worthy of considering that conflict that might be seen to arise when medical practitioners put themselves at risk in caring for their patients.

Healthcare workers should never be put in a position where fears about the adequacy of personal protective equipment interfere with their duty to the patient.

The responsibility of those that govern us, from our parliaments to our health services and hospitals, is to protect us, both with appropriate legislative and governance frameworks, and the physical resources to self-care.

Anything less is to put us in breach of our code of ethics and our responsibility to our patients.

References

- World Medical Association. WMA Declaration of Geneva. 2018. Available from: www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-geneva/.

- World Medical Association. WMA Declaration of Geneva. 2018. Available from: www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-geneva/.

Leave a Reply