Compared to their singleton counterparts, twins have a perinatal mortality rate three and a half times higher,1 a rate that has seen minimal change over the past 20 years despite significant advances in perinatal care. It is no surprise then that, while twins account for less than 3% of all pregnancies,2 no maternity care clinician is unfamiliar with the complexities and challenges of twin pregnancies. In particular, much debate continues about choices and decisions regarding the preferred mode of birth for ‘uncomplicated’ twins. This is likely owing, in part, to the relative lack of high-level evidence to guide clinical practice. While a number of retrospective cohort studies had suggested that elective caesarean section was safer than planned vaginal birth,3 4 it wasn’t until 2013 that the Twin Birth study, the first randomised clinical trial (RCT) of planned mode of birth in twins, showed that elective caesarean section was not associated with better perinatal outcomes than planned vaginal birth.5 Eight Australian hospitals participated in the study. One might have expected that the debate would end there, with a definitive RCT. But, no!

Since the publication of the Twin Birth study, the debate has continued. Authors of further cohort studies have argued that planned vaginal birth is as safe as elective caesarean section,6 7 while other have argued the opposite.8 Most recently, a re-analysis of the Twin Birth study, taking into account gestation as a possible confounder of outcome, showed that planned vaginal birth was safer than caesarean section from 32 to 37 weeks, but from 37 weeks onwards an elective caesarean section may be more favourable.9 No wonder confusion reigns, both among women pregnant with twins and among the clinicians providing them care. So, what is the preferred mode of birth for twins in Australia? Recently, we sought to answer that question for Victoria and to understand possible explanations for any changes.

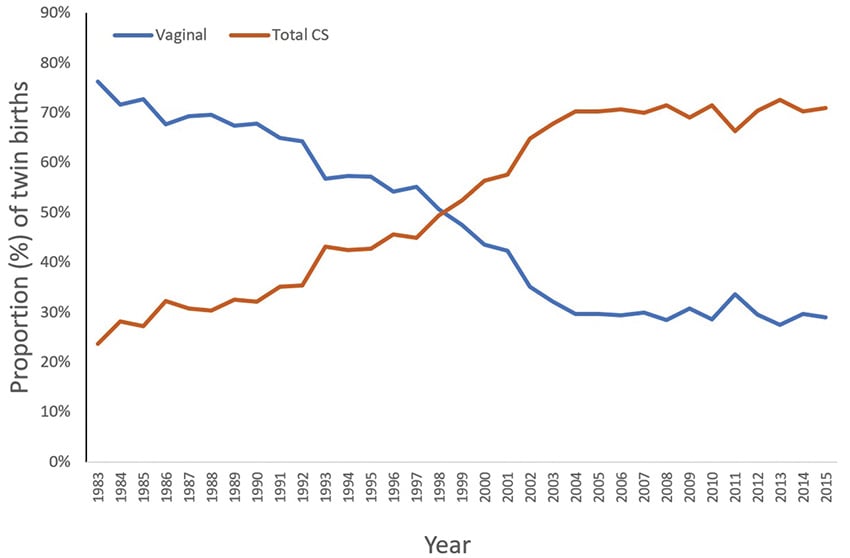

First, the changes. We looked at the mode of birth for twin pregnancies in Victoria over a 33-year period, 1983 to 2015.10 Over this time, there has been a three-fold increase in both planned and unplanned caesarean section. The proportion of twins born vaginally has fallen from 76% to 29%.11 Almost all of this change happened before 2005. Since then, the rates of caesarean section and vaginal birth for twins have been relatively stable (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Trends in modes of twin birth in Victoria between 1983–2015. (adapted from Liu et al)

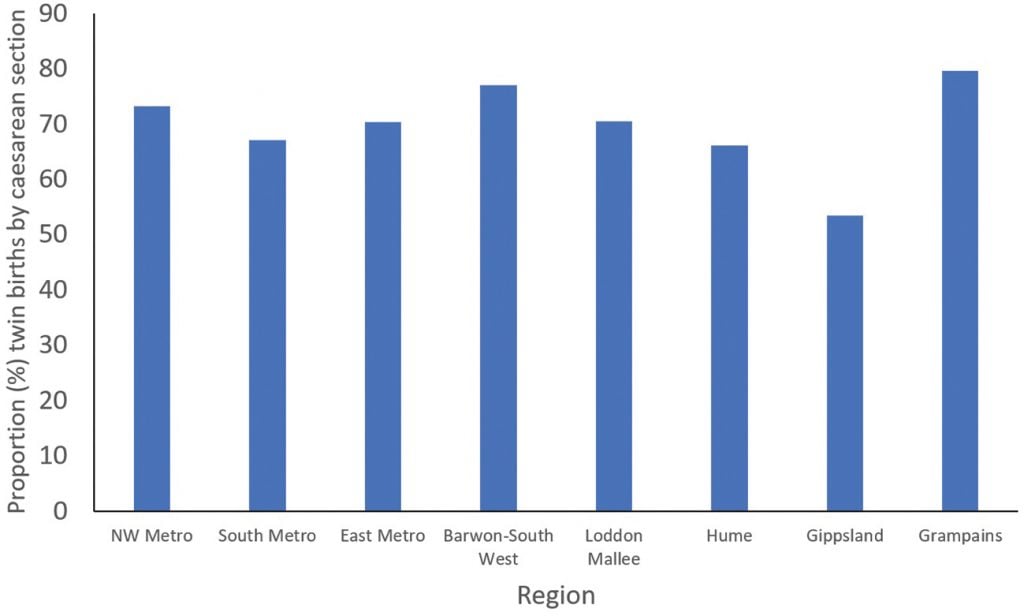

Next, we sought to understand the principal reasons for the changes in mode of birth over time. Were they due to increasingly complex twin pregnancies, or more maternal co-morbidities or pre-existing maternal disease? They weren’t. We found that, over time, ‘twins’ itself has become the main indication for caesarean section, with no other indication. This was true irrespective of maternal age or parity. We also found significant regional variation in the rate of caesarean section for twins across the state (Figure 2), with rates varying by over 25%. After adjusting for maternal age, body mass index, parity, previous caesarean section, public or private care, and use of assisted reproductive technology, women living in Gippsland were half as likely to have twins born by caesarean section than women living in north-west metropolitan Melbourne or the Grampians (adjusted odds ratio 0.46).12 Consistent with the Twin Birth study,13 we didn’t find any evidence that the increased use of caesarean section has been associated with better perinatal outcomes.

Figure 2. Rates of twin caesarean section by Victorian region. (adapted from Liu et al)

Of course, there was only two years between the publication of the Twin Birth study and the end of the data set that we analysed. Possibly insufficient time for the findings of the study to change practice. However, perhaps a more pressing implication of our observations is in relation to the maintenance of a skilled workforce. In 1983, the first year of our data set, there were 502 sets of twins born vaginally. In 2015, there were 320. The same year, there were 152 FRANZCOG trainees across six-year levels. This crudely equates to each trainee attending two twin vaginal births a year. It shouldn’t be surprising then that a recent survey of RANZCOG members and new Fellows found that 34% of trainees and 15% of Fellows did not feel sufficiently experienced in twin vaginal births.14 There is no requirement within the RANZCOG training syllabus for trainees to demonstrate competence in twin vaginal birth. Without due care, we could have a Fellowship workforce that is unable to offer women with a twin pregnancy safe choices about mode of birth. As we argued in our recent paper, ‘We should ensure that we have a skilled and competent workforce to enable women to have a real choice in how their babies are born.’15

However, perhaps not all is lost. That the rate of twin vaginal birth hasn’t materially changed in over 15 years is somewhat reassuring. Perhaps it is time, if not overdue, that all women with a twin pregnancy are cared for by multidisciplinary clinical teams with expertise in multiple pregnancy, including vaginal birth. We are not arguing for centralisation of twin pregnancy care to large city hospitals. That is not necessary, nor in the best interests of women. In Victoria, the highest rate of twin vaginal birth is in a regional hospital. Rather, we are arguing for women with a twin pregnancy to be cared for by clinicians who are experienced, confident and skilled in being able to offer them safe choices. That way, outcomes would likely improve, and training opportunities could be better concentrated into dedicated units.

References

- Consultative Council on Obstetric and Paediatric Mortality and Morbidity. Victoria’s Mothers, Babies and Children 2014 and 2015. Melbourne: Victorian Government; 2017. Available from: www.bettersafercare.vic.gov.au/reports-and-publications/victorias-mothers-babies-and-children-report-2014-15

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australia’s mothers and babies 2015—in brief. Canberra: AIHW; 2017. Available from: www.aihw.gov.au/reports/mothers-babies/australias-mothers-babies-2015-in-brief/contents/table-of-contents

- Smith GC, Shah I, White IR, et al. Mode of delivery and the risk of delivery-related perinatal death among twins at term: a retrospective cohort study of 8073 births. BJOG. 2005;112(8):1139-44.

- Armson BA, O’Connell C, Persad V, et al. Determinants of perinatal mortality and serious neonatal morbidity in the second twin. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(3 Pt 1):556-64.

- Barrett JFR, Hannah ME, Hutton EK, et al. A Randomized Trial of Planned Cesarean or Vaginal Delivery for Twin Pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(14):1295-305.

- Schmitz T, Prunet C, Azria E, et al. Association Between Planned Cesarean Delivery and Neonatal Mortality and Morbidity in Twin Pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129(6):986-95.

- Hofmeyr GJ, Barrett JF, Crowther CA. Planned caesarean section for women with a twin pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2015(12):CD006553.

- Goossens S, Ensing S, van der Hoeven M, et al. Comparison of planned caesarean delivery and planned vaginal delivery in women with a twin pregnancy: A nation wide cohort study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2018;221:97-104.

- Zafarmand MH, Goossens S, Tajik P, et al. Planned Cesarean or planned vaginal delivery for twins: a secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2019. doi: 10.1002/uog.21907.

- Liu YA, Davey MA, Lee R, et al. Changes in the modes of twin birth in Victoria, 1983-2015. MJA. 2020;212(2):82-8.

- Liu YA, Davey MA, Lee R, et al. Changes in the modes of twin birth in Victoria, 1983-2015. MJA. 2020;212(2):82-8.

- Liu YA, Davey MA, Lee R, et al. Changes in the modes of twin birth in Victoria, 1983-2015. MJA. 2020;212(2):82-8.

- Smith GC, Shah I, White IR, et al. Mode of delivery and the risk of delivery-related perinatal death among twins at term: a retrospective cohort study of 8073 births. BJOG. 2005;112(8):1139-44.

- Yeoh SGJ, Rolnik DL, Regan JA, Lee PYA. Experience and confidence in vaginal breech and twin deliveries among obstetric trainees and new specialists in Australia and New Zealand. ANZJOG. 2019;59(4):545-9.

- Liu YA, Davey MA, Lee R, et al. Changes in the modes of twin birth in Victoria, 1983-2015. MJA. 2020;212(2):82-8.

Leave a Reply