Prior surgery to the abdomen presents access challenges for the obstetrician. Our patient had complex anatomy due to repeat laparotomies for Crohn’s disease. Advances in other fields, such as colorectal surgery and IVF, may result in high-risk obstetric patients, with medical, surgical and neonatal considerations.

Case Description

Mrs KB was a 35-year-old (G2P0) woman at 34+6 weeks, who presented with threatened preterm labour and antepartum haemorrhage in the setting of major placenta praevia. This was an IVF pregnancy for tubal factor infertility. She had a significant surgical history of Crohn’s disease, with peri-anal and vulval involvement, currently in remission. In 2005, Mrs KB had a procto-colectomy and permanent end-ileostomy. In 2018, a repeat midline laparotomy involved partial small bowel resection, appendicectomy, revision ileostomy and de-roofing of large bilateral hydrosalpinges.

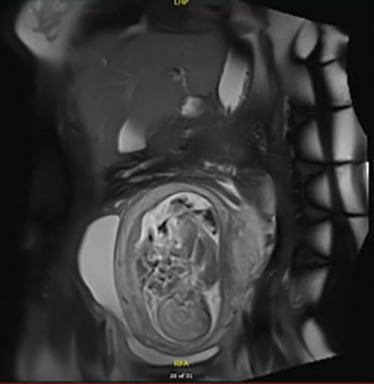

Her other active medical conditions were rheumatoid arthritis, asthma and chronic pain, with medications including vedolizumab and azathioprine. She had a previous miscarriage, was O Rhesus positive, antibody negative and serology negative, with a normal booking BMI of 25. The gastroenterology team ordered an antenatal MRI (Figure 1) at 19 weeks for fever and abdominal pain, which subsequently resolved.

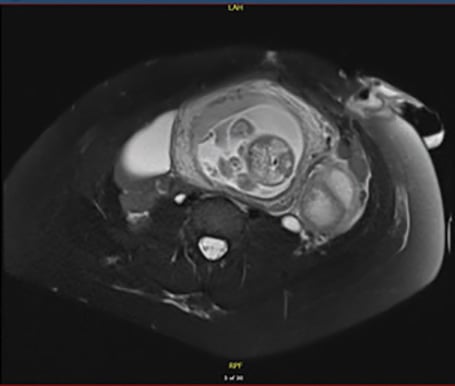

Figures 1a & 1b. Antenatal MRI at 19 weeks shows coronal and transverse MRI views of the abdomen and pelvis, with a complex multi cystic 5.9cm mass in the left pelvis, may be ovarian in origin. Moderate amount of free fluid, partly septated, in the pouch of Douglas and along the right side of the gravid uterus. No bowel wall thickening. Previous colectomy with left iliac fossa stoma.

Her 20 week ultrasound showed normal morphology, but identified grade 4 placenta praevia, posterior and extending 1cm across the internal os. A repeat scan at 25 weeks demonstrated estimated fetal weight (EFW) 86th centile with multiple left ovarian cysts and loculated fluid in the right adnexa.

She had a major antepartum hemorrhage (APH) of 250ml at 28+4, necessitating a paediatric infant perinatal emergency retrieval transfer to a tertiary hospital and celestone loading. CTG was normal after a period of observation, then the patient self-discharged against medical advice. At 31 weeks, the EFW was 51st centile, with persistent free fluid in POD measuring 66x47x52mm and right adnexal fluid measuring 51x59x38mm. At 33 weeks, the EFW was 77th centile.

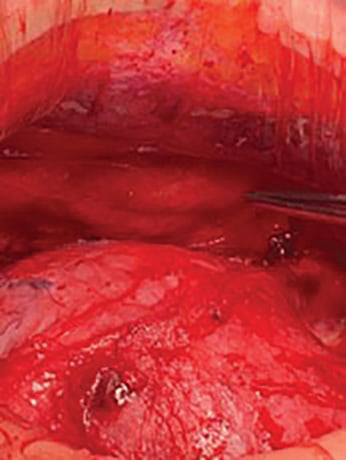

At 34+6 weeks, she had her second presentation of APH, with palpable tightenings and an otherwise reassuring fetal CTG trace. An emergency caesarean section was performed, under general anaesthesia as per patient request. On the external abdomen, there was dense scaring of the midline, with a left lower quadrant ileostomy (Figure 2a). A Pfannenstiel incision was made after discussion with the colorectal team, who suggested no advantage to midline entry.

On entering the pelvis, the peritoneal planes were poorly differentiated. The pelvic cavity was walled off posteriorly, with the round ligaments identified bilaterally but unable to visualise tubes or assess ovaries. The abdominal cavity was also walled off superiorly, with the underside of the ileostomy seen and no bowel visible (Figure 2b). Manipulation of the uterus was not possible, as it was plastered towards the left.

Figures 2a & 2b. Intra-operative photography shows a) Left iliac fossa ileostomy, previous repeat midline laparotomy scar. b) Abdominal findings: uterus (inferior), walled off from undersurface of ileostomy (superior, pointed to by forceps).

At transverse uterine incision, there was clear bloodstained liquor with no overt abruption, and a massive postpartum haemorrhage with an estimated blood loss of 1.5L. The male baby was born with poor respiratory condition and a neonatal code blue was called with appearance, pulse, grimace, activity and respiration 2 at one minute and 8 at 10 minutes, after intermittent positive-pressure ventilation for resuscitation. He was treated for presumed sepsis, jaundice and prematurity.

Mrs KB’s postoperative course was complicated by recurrent medical emergency calls for pain, tachycardia and hypotension on day 1 post operation. She was prescribed patient-controlled anaesthesia and was admitted to ICU on day 2 for observation.

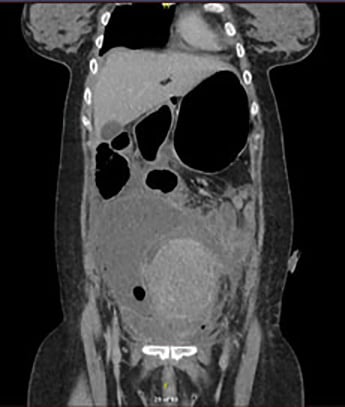

A CT abdomen pelvis (Figure 3) demonstrated two large collections superior/right and anterior of the uterus. Whilst described as likely infective, the colorectal team advised against immediate return to theatre as it could be postoperative changes and had been pre-existing on prior imaging. She was conservatively managed with nasogastric tube, peripherally inserted central catheter line for IV tazocin and bowel rest.

Figures 3a & 3b. Day 2 post emergency caesarean section. Coronal and transverse CT, demonstrating two large collections of the superior and right side of the uterus (15x14x9cm) and at the anterior aspect of the uterus (9x6x3cm), presumed infective. Small to moderate ascites. Distended proximal loops of small bowel, which taper distally without a transition nor point of obstruction demonstrated.

On day 3, Mrs KB was hypotensive and noradrenaline was commenced for persistent tachycardia. A CTPA demonstrated left lower lung collapse and bilateral atelectasis, but no pulmonary embolism. Noradrenaline was ceased day 4, abdominal pain improved, and antibiotics were stepped down to oral Augmentin Duo Forte on day 5. Septic screen revealed ureaplasma on a high vaginal swab and a course of azithromycin, as per the ID team, was given in the setting of a potentially immune-compromised patient with Crohn’s Disease. A transabdominal ultrasound on day 8 demonstrated ongoing pelvic free fluid that appeared simple in nature (Figure 4) prior to discharge.

Figure2 4a & 4b. Day 8 post emergency caesarean section. Ultrasound showing 230ml free fluid, anechoic, within the pouch of Douglas/posterior pelvis.

Discussion

Multi-disciplinary team

This case highlights the importance of a multi-disciplinary team (MDT) approach. The Victorian hospital capability framework1 provides guidance to the severity of obstetrics cases recommended per level 1 to 6, pertaining to the site of surgery. The patient presented at 34+6 weeks to our outer-metropolitan level 5 general hospital with threatened preterm labour and APH, just prior to an MDT meeting scheduled for 35 weeks. Of note, communication had already occurred between medical, surgical, and high-risk obstetrics teams. Ideally, we would have extended involvement to our anesthetics, paediatric, ICU and radiology colleagues, to ensure best planning and awareness of the case.

Inflammatory bowel disease, pregnancy and ileostomy

A recent 2019 gastroenterology guideline stated that the risks of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) to a pregnancy are ‘significant and manifold’, including ‘miscarriage, intrauterine growth restriction, premature delivery, poor maternal weight gain, and complications of labour and delivery, such as preeclampsia, placental abruption, and increased probability of cesarean delivery’.2

They recommended consultation with a maternal-fetal medicine (MFM) specialist, particularly for those with ‘prior laparotomy, ostomy or ileal pouch-anal anastomosis surgery’.3 While the MFM specialist can ‘determine the type of monitoring needed, in most cases it will be the general obstetrician who attends the delivery.’4

Specifically, in regards to ileostomy and caesarean section, early case reports have been published over 60 years ago.5 Review of the literature is usually associated with good outcomes.6 Some novel complications, such as a compressed ileostomy by gravid uterus in the third trimester, have been reported.7 Whilst caesarean section was indicated due to the major placenta praevia in our case,8 it should be noted that per se an ileostomy itself does not preclude a vaginal delivery9 10 11 and that a caesarean has specific risks in IBD, including adhesions, pelvic sepsis and bowel/viscus perforation.12

The postoperative patient who decompensates requires clinical judgement. Specifically in this case, the necessity and advisability of return to theatre given the CT findings of presumed infective fluid. Given her abnormal vital signs of tachycardia and hypotension, she was closely observed in the ICU. She had successful conservative management of her intra-abdominal collections, which appeared pre-existing in nature, with a nasogastric tube as part of bowel rest for ileus.

Intra-peritoneal anatomy

In terms of anatomy, we identified a second peritoneal cavity, defined by the uterus posterior/inferiorly, and walled off by the ileostomy anterior/superiorly. This presented difficultly identifying the location of fluid on the CT abdomen. Particularly, the accumulation of fluid anterior to uterus, difficult to interpret query infected fluid from pre-existing abdominal free fluid.

Conclusion

The approach to the patient with IBD and a stoma requires specific attention to anatomy, stoma function and postoperative imaging changes. The Pfannenstiel incision was made away from the stomal site to avoid potential devascularisation injury to the ileostomy. This patient’s course was complicated by presumed sepsis, pain and admission to ICU. Timing of the MDT is also important, as the patient went into threatened preterm labour prior to the combined meeting. It poses the question: when is it best to triage complex cases and consider referral? Furthermore, what should be done in the emergency setting to determine the suitability for continued care at the presenting hospital in order to ensure best practice?

References

- Department of Health and Human Services. Capability frameworks for Victorian maternity and newborn services. Maternity and newborn care in Victoria; 2019. Available from: www2.health.vic.gov.au/hospitals-and-health-services/patient-care/perinatal-reproductive/maternity-newborn-services/maternity-newborn-care

- Mahadevan U, Robinson C, Bernasko N, et al. Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Pregnancy Clinical Care Pathway: A Report from the American Gastroenterological Association IBD Parenthood Project Working Group. American Gastroenterological Association. 2019;220(4):308-23.

- Mahadevan U, Robinson C, Bernasko N, et al. Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Pregnancy Clinical Care Pathway: A Report from the American Gastroenterological Association IBD Parenthood Project Working Group. American Gastroenterological Association. 2019;220(4):308-23.

- Mahadevan U, Robinson C, Bernasko N, et al. Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Pregnancy Clinical Care Pathway: A Report from the American Gastroenterological Association IBD Parenthood Project Working Group. American Gastroenterological Association. 2019;220(4):308-23.

- Priest F, Gilchrist R, Long J. Pregnancy in the patient with ileostomy and colectomy. JAMA. 1959;169(3):213-15.

- Madu AE. Subtotal colectomy and ileostomy in early pregnancy and review of relevant medical literature. Gynecol Obstet Case Rep. 2016;2(2).

- Porter H, Seeho S. Obstructed ileostomy in the third trimester of pregnancy due to compression from the gravid uterus: diagnosis and management. BMJ Case Report. 2014.

doi: 10.1136/bcr-2014-205884 - Placenta Praevia and Placenta Accreta: Diagnosis and Management. BJOG. 2019;126(1):1-48.

- Mahadevan U, Robinson C, Bernasko N, et al. Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Pregnancy Clinical Care Pathway: A Report from the American Gastroenterological Association IBD Parenthood Project Working Group. American Gastroenterological Association. 2019;220(4):308-23.

- Priest F, Gilchrist R, Long J. Pregnancy in the patient with ileostomy and colectomy. JAMA. 1959;169(3):213-15.

- Madu AE. Subtotal colectomy and ileostomy in early pregnancy and review of relevant medical literature. Gynecol Obstet Case Rep. 2016;2(2).

- Madu AE. Subtotal colectomy and ileostomy in early pregnancy and review of relevant medical literature. Gynecol Obstet Case Rep. 2016;2(2).

Leave a Reply