Interventional radiology (IR) is a rapidly growing subspecialty that allows minimally invasive treatment of a multitude of conditions in a number of body systems under image guidance.

Rather than a referral service like diagnostic radiology, interventional radiology is gaining recognition worldwide as a clinical specialty in its own right. This involves giving opinions on patient care at multidisciplinary meetings, seeing patients in clinic pre and post procedure and managing in-patient care.

Interventional radiology is reshaping current practice in many clinical specialties and obstetrics and gynaecology is no exception.

In this article we will outline interventional radiology options for the management of fibroids and pelvic vein congestion.

Fibroid embolisation

After being first reported in 1995,1 uterine artery embolisation (UAE) has since established itself as a safe and efficacious treatment for uterine fibroids, with comparable quality of life outcomes (QOL) to surgery. It is now included in multiple guidelines for uterine fibroid treatment by bodies around the world including the American College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology and the Royal College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. These guidelines recognise the comparable quality of life outcomes to surgery, but with the caveat of an increased re-intervention rate. Despite this, it has been globally underutilised, particularly in Australia and New Zealand. One study found uterine artery embolisation represented approximately 2.7% of the number of surgical procedures performed for uterine fibroids under the Medicare system.2

It is vital to have our gynaecology colleagues on board with the current data on uterine artery embolisation and recognise the potential benefits to patients. A study in the Netherlands3 found that several misconceptions prevailed about uterine artery embolisation with regards to its efficacy (40% of gynaecologists responding felt uterine artery embolisation was ineffective, despite extensive data and guidelines confirming otherwise) and rate of eventual hysterectomy (half of respondents felt that there was a 50% risk of eventual hysterectomy, EMMY trial showed this is in the order of 31% at 10 years,4 sparing almost 70% from significant surgery).

Patient experience with uterine artery embolisation is also undergoing refinement with the increasing adoption of trans-radial access and the use of either the superior hypogastric nerve block (SHGNB),5 intra-arterial lidocaine or combination thereof. Both the access and analgesic adjuncts allow for faster mobilisation, reduced peri-procedural discomfort and earlier discharge. In our experience, the vast majority of women prefer to be at home for the night following the procedure. It has been demonstrated that a same day discharge protocol is feasible with a low rate of early return (0.5% re-admission rate).6

In a recent randomised controlled trial (FEMME trial)7 myomectomy was compared to uterine artery embolisation , and a marginal difference in quality of life outcome was determined in favour of myomectomy. Final quality of life score 84 (myomectomy) vs 80 (uterine artery embolisation ), the very modest difference being of dubious clinical significance, also of note the symptom score component showed no difference between the two interventions at one or two years. This study further confirms the high efficacy of uterine artery embolisation.

Technique

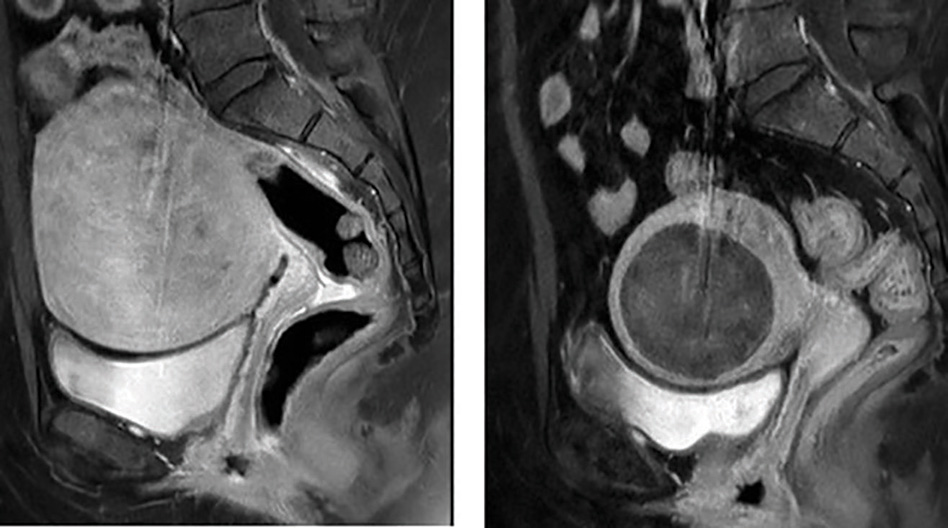

In our institution, patients for uterine artery embolisation are seen in interventional radiology clinic after having an MRI, which helps identify location, size and vascularity of fibroids as well as variant arterial anatomy or collateral ovarian arterial supply.

Pre-procedural analgesia, anti-emetic and antibiotics are given, and the procedure is performed under conscious sedation. A 5Fr sheath is inserted into the left radial artery. Each uterine artery is selectively catheterised in turn and small PVA particles (500–700 micron) are delivered to achieve stasis of flow. A superior hypogastric nerve block with 20ml of 0.25% Ropivacaine is performed, which lasts approximately 8–12 hours. Overall procedural duration is 30–60 minutes. The patient has an inflatable wristband placed at the access site to achieve haemostasis and this is deflated over the course of 45 minutes. Discharge occurs four hours after the procedure, provided she has adequate control of her pain.

Pelvic congestion syndrome

Pelvic congestion syndrome (PCS) is one of the most underdiagnosed causes of chronic pelvic pain in women. It is defined as the presence of ovarian and pelvic varicose veins associated with chronic pelvic pain persisting longer than six months, exacerbated by prolonged standing, coitus and menstruation.8

It typically affects young multiparous women in their 20s to 30s and is usually diagnosed after excluding other causes such as adenomyosis, endometriosis, urological and gastrointestinal problems.

Pelvic congestion syndrome caused by incompetent or absent venous valves is known as pelvic venous insufficiency (PVI) and is analogous to the varicocele in men. Valves are absent from the ovarian veins in 15% of women and incompetent on the left and right in 40% and 35% respectively.9 Other causes can be external compression of pelvic venous drainage at the left common iliac vein, May-Thurner Syndrome, or the left renal vein, Nutcracker Syndrome.

Diagnosis

Catheter venography is the gold standard for diagnosis, but this is invasive and requires ionising radiation. It is best reserved for cases that are inconclusive on non-invasive imaging or for treatment.

Transabdominal and transvaginal doppler ultrasound is usually the go to modality allowing non-invasive dynamic assessment. Criteria for diagnosis include dilated tortuous ovarian and parauterine veins (>4mm) with slow or retrograde flow. Valsalva can be used to accentuate reflux.10

Time resolved MR angiography (Figure 1) has been shown to be an accurate method of diagnosing ovarian vein reflux and multiplanar MRI is excellent for diagnosing alternate causes of pelvic pain.11

Figure 1. Sagittal MRI T1 post-contrast. a) Pre-embolisation, demonstrating large enhancing fibroid b) Post-embolisation, showing volume reduction and non-enhancement of the fibroid.

Endovascular treatment

This is performed as a day case procedure under local anaesthetic and light sedation from either a jugular or femoral venous approach. It is safe, effective and durable.12

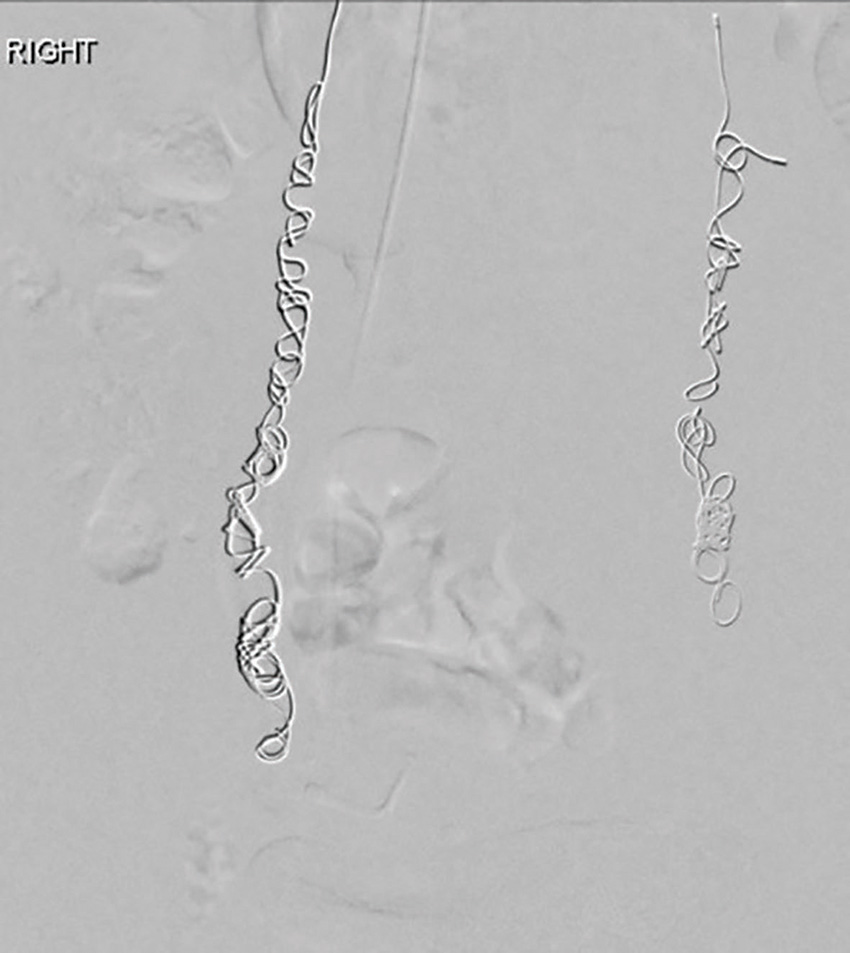

The aim is to occlude the incompetent veins as close to the origin of reflux as possible (Figure 2). There are two approaches to treatment. The first is to stage the treatment with ovarian vein embolisation and if there are ongoing symptoms to then embolise the internal iliac veins. The second is to do a complete embolisation of all four territories in one sitting.

Embolisation can be performed with coils and plugs with or without liquid embolics such as sclerosant (3% sodium tetradecyl sulfate) and glue (Figure 2b).

Technical and clinical success is high with complications rare. Immediate complications include haematoma at the puncture site or in the target vein, non-target embolisation and stroke. Delayed complications include coil migration.

Figure 2. MR venogram demonstrating incompetent left ovarian vein.

Figure 2b. Post-embolisation with coils in both ovarian veins.

Summary

The literature shows that transcatheter embolisation is a safe, effective and durable option for the treatment of fibroids and pelvic congestion syndrome. Interventional radiologists working together with gynaecologists would allow better patient selection and education, ultimately enabling women to make an informed choice regarding their treatment.

References

- Ravina JH, Herbreteau D, Ciraru-Vigneron N, et al. Arterial embolization to treat uterine myomata. Lancet. 1995;346(8976):671-2.

- Makris GC, Butt S, Sabharwal T. Unnecessary hysterectomies and our role as interventional radiology community. CVIR Endovasc. 2020;3:46.

- de Bruijn AM, Huisman J, Hehenkamp WJK, et al. Implementation of uterine artery embolization for symptomatic fibroids in the Netherlands: an inventory and preference study. CVIR Endovasc. 2019;2(1):18.

- de Bruijn AM, Ankum WM, Reekers JA, et al. Uterine artery embolization vs hysterectomy in the treatment of symptomatic uterine fibroids: 10-year outcomes from the randomized EMMY trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(6):745.e1-745.e12.

- Pereira K, Morel-Ovalle LM, Taghipour M, et al. Superior hypogastric nerve block (SHNB) for pain control after uterine fibroid embolization (UFE): technique and troubleshooting. CVIR Endovasc. 2020;3:50.

- Sher A, Garvey A, Kamat S, et al. Single-System Experience With Outpatient Transradial Uterine Artery Embolization: Safety, Feasibility, Outcomes, and Early Rates of Return. American Journal of Roentgenology. 2021;216:975-80.

- Manyonda I, Belli AM, Lumsden MA, et al. Uterine-Artery Embolization or Myomectomy for Uterine Fibroids. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:440-51.

- Harris RD, Holtzman SR, Poppe AM. Clinical outcome in female patients with pelvic pain and normal pelvic US findings. Radiology. 2000;216:440-3.

- Freedman J, Ganeshan A, Crowe PM. Pelvic congestion syndrome. The role of interventional radiology in the treatment of chronic pelvic pain. Postgrad Med J. 2010;86: 704-10.

- Bookwalter CA, VanBuren WM, Neilen MJ, et al. Imaging appearance and non surgical management of pelvic venous congestion syndrome. Radiographics. 2019;39:596-608.

- Yang DM, Kim HD, Nam DH, et al. Time-resolved MR angiography for detecting and grading ovarian venous reflux: comparison with conventional venography. Br J Radiol. 2012;85: e117-e122.

- Hansrani V. Abbas A, Bhandari S, et al. Trans-venom occlusion of incompetent pelvic veins for chronic pelvic pain in women: A systematic review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2015;185:156-163.

Leave a Reply