Imagine a medical consultation with no direct language communication between the physician and the patient. This is what happens when the patient is a young child, or an older person who is suffering cognitive impairment. Or when the healthcare professional and patient do not share a common language. These scenarios are not atypical, and there are work-arounds, in the form of a parent, a family member or friend, or an interpreter.

We propose that pelvic pain also represents a condition where a common language is lacking. Where language linking a woman’s experience with known pathologies has not been adequately developed. Where factors including gender, cultural background, age, ethnicity, education and language competence all affect the description of pain and add to potential misunderstandings.1 2 3 4

From the point of view of the physician, around 50% of Australia’s health professionals come from overseas. While many of these professionals do indeed come from English-speaking countries, or at least underwent English-speaking medical training, intercultural communication is an increasingly complicated aspect of medical care in Australia.4,6 For example, in many parts of Asia, patients are traditionally taught that it is inappropriate to ask unprompted questions of a doctor, and doctors do not expect such questions. Many follow these practices in medical consultations in Australia.

These factors are even more complex when we consider pain in women. Strong et al5 asked male and female students to write about their experience of severe pain. Women used a more elaborate repertoire of pain expressions than a comparable cohort of males. They used more individual pain words from the McGill Pain Questionnaire,6 more evocative language, and more elaborate descriptions involving figures of speech like similes:

The swelling felt like the skin would burst and the burning in the bone made me feel like my head would explode.

Males were more likely to use concrete expressions and, on occasion, vulgar language.

Accurate epidemiological data on the prevalence of pelvic pain remains incomplete. However, Parker et al7 have shown that 20% of a cohort of school-age female students in Canberra suffered significant dysmenorrhoea, and variable degrees of associated pelvic pain conditions. Delgado8 puts the prevalence of pelvic pain at 15%–20%; and Lamvu et al9 estimate that chronic pelvic pain affects 26% of the world’s female population. For women in pain, the question of ‘frank and full’ communication is even more complicated, as the pelvis includes organs and functions related to two of the strongest taboos in language and culture: reproduction and the elimination of bodily wastes.10 Despite this, women may put substantial effort into describing what their pain feels like, in an attempt to convey useful information to their health practitioner.

Considerations like these have led us to launch a program of research into a more deep-reaching understanding of pelvic pain talk, and how this may facilitate improved communication between women with pelvic pain and health practitioners. History-taking in medicine involves pattern recognition. Descriptions of pain and their correlation with underlying pathologies have been developed over centuries. For example, a gnawing pain in the right hypochondrium that radiates to the right shoulder, associated with nausea or vomiting, suggests gall bladder disease. A constant pain in the upper abdomen that radiates to the back, associated with diarrhoea and weight loss, may indicate pancreatitis. The single-word language of pain in these organs – gnawing, constant – has been well tested over time. They are not unique descriptors, but they do point a diagnosis strongly in specific directions for further exploration.

But what of pelvic pain, and the many varied descriptions women use, especially where laparoscopy and scans are normal, and no diagnosis has been made? We suggest that the language of pelvic pain has not yet benefited from this kind of evidence. A number of the relevant female pain symptoms were categorised under the psychiatric diagnosis ‘Hysteria’ until DSM 11 12 and were only removed in 1987. Outside the framework of DSM 3, chronic female pelvic pain has been left without structured diagnostic links. It is disconcerting for both patients and physicians to be unable to associate pain with specific pathologies, especially when it is so difficult to characterise the many kinds of female chronic pelvic pain. There is a risk that delayed or uncertain diagnoses may lead to indecisive or inconclusive treatment.

Is there a distinct language for female pelvic pain, parallel to the ways in which language can help to point to gall bladder pain or pancreatitis? Can we match pain descriptors with an organ system, or an underlying pain mechanism? Can we determine the common pain descriptors and how they are used? And more broadly, can we improve communication between a woman and her health practitioner?

Our group has recently undertaken an online survey into women’s pelvic pain. We asked women to describe their pain, fully and frankly, using as many words as they wished. The response from women in pain was overwhelming. We are engaged in analysing this rich data source using language analysis software to develop a Language of Pelvic Pain.

We now present some select initial findings from this ongoing research. These findings specifically consider dysmenorrhoea-related pelvic pain.

A data-based diagnostic approach to language and female pelvic pain

A convenient place to start is single-word pain descriptors. This approach to the identification and characterisation of pain has an established place in pain studies since the introduction of the McGill Pain Questionnaire,13 which used 78 adjectives and a scoring algorithm to assess especially the intensity and subjective effect of pain. Our approach focuses also on the relation of words to triangulation and pattern-recognition in medical diagnosis.

We surveyed 1034 women in Australia and New Zealand through an online platform to allow them to describe their pain, using both structured check boxes and free-form input boxes for them to express their pain in their own words. Ethics approval was granted from the University of Adelaide. We asked what the pain felt like and how such pains affected their lives. We collected over 300,000 words in these responses.

Collating different survey responses, we now know that stabbing pains are highly associated with more severe dysmenorrhoea, more days with pain each month, have a more severe impact on a woman’s quality of life, and can lead to a higher level of depression, anxiety and stress.

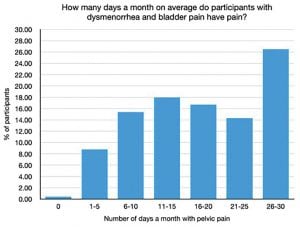

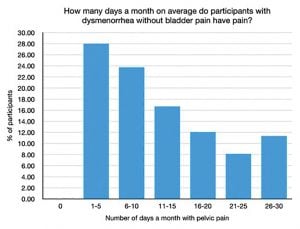

We also know that certain types of pain are commonly associated with each other, for example, the association of dysmenorrhea with bladder pain. Our survey showed that women with both dysmenorrhea and bladder symptoms have more pain on more days each month compared to their counterparts without bladder symptoms.14

There is also a correlation of pelvic pain with the most common terms used to describe it. Of the 468 women with both dysmenorrhea and bladder pain, 419 women described their pain as stabbing. Stabbing pain has been associated with the presence of a pelvic muscle component to pain. These associations between certain pains are consistent with the consensus view among pain specialists that chronic pain involves central sensitisation and chronic inflammation.

But we can go further than the numbers. The data from the free-form responses to the survey on the language of pelvic pain revealed some strong patterns in the language used to describe pelvic pain. The survey divided pelvic pain into five categories: pain with periods, pain of the vulva, bowel and bladder, and pain with sex. The five overall most common words to describe pelvic pain, in ranked order, were:

PELVIC PAIN: sharp, stabbing, cramping, ache, dull

And these were also the most common words (though not in that ranked order) for period pain: the ranked order for period pain was: cramping, sharp, stabbing, dull, ache. Period pain, if you will, is closest to the stereotypical model for pelvic pain. But bowel pain did not rate ache and dull in the top five. Its ranked order was:

BOWEL PAIN: sharp, stabbing, cramping, burning, intense

Nor did bladder pain include dull:

BLADDER PAIN: sharp, ache, aching, burning, constant

What is important is not only the presence of individual pain descriptors, since both bowel and bladder pain lack dull in their top five. We can see here the beginnings of a symptom-specific approach to using language for diagnosing different aspects of pelvic pain, but one where single-word approaches will have to be supplemented by multiple-word pain profiles. The triangulation between statistics and qualitative language data, combined with tactile, mechanical and biochemical information, may provide a level of definition which is currently not possible.

Beyond the single-word diagnostic tool

These preliminary results point clearly to potential applications in medical diagnosis. Thus far we have concentrated on single-word characterisations of varieties of pelvic pain. We do not expect to discover unique pain descriptors that will point uniquely to specific aspects, lesions, or symptoms of pain. But we do expect, on the basis of research already completed, that there will be patterns of language use that are indeed indicative of the presence of certain types of pain, enabling better identification, consideration and diagnosis for women with chronic pelvic pain. There is evidence, in our data, that single-word pain characterisations are powerfully enhanced, in the pain descriptions, by women who extend their pain language into the expressive properties of phrases, similes, metaphors and more. And these characterisations of pain require the rich language-based channel of communication with which we began this paper. These narratives and conversations, if fully pursued, should help to establish a channel of communication between the physician and the patient; to build empathy and trust; to enhance the chances of an appropriate diagnosis; and to support the formulation of management plans, especially for chronic pain conditions in women.

Conclusion

In this endeavour, we have a strong holistic focus on the quality of life of women with pelvic pain. We wish to improve the understanding between women and their health practitioners that facilitates the understanding and management of pelvic pain for both women and their treating health practitioner. For this purpose, the role of language and communication is fundamental.

Related article

Pelvic pain experience: to be believed and heard

Our feature articles represent the views of our authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RANZCOG), who publish O&G Magazine. While we make every effort to ensure that the information we share is accurate, we welcome any comments, suggestions or correction of errors in our comments section below, or by emailing the editor at [email protected].

References

- Sussex R. The language of pain in Applied Linguistics. Review article of Chryssoula Lascaratou’s The Language of Pain. (Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 2007). Australian Review of Applied Linguistics. 2009;32(1):6.1-6.14.

- Zborowski M. People in Pain. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1969.

- Perović M, Jacobson D, Glazer E, et al. Are you in pain if you say you are not? Accounts of pain in Somali–Canadian women with female genital cutting. Pain. 2021;162(4):1144–52. doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000002121.

- Sussex R. Pain as an issue of intercultural communication. In: Curtis A, Sussex R editors. Intercultural communication in Asia: education, language and values. Berlin and London: Springer Verlag; 2018: 181-204.

- Strong J, Mathews T, Sussex R, et al. Pain language and gender differences when describing a past pain event. Pain. 2009;14 86–95.

- Melzack R. The McGill Pain Questionnaire: major properties and scoring methods. Pain. 1975;1:277–99.

- Parker MA, Sneddon AE, Arbon P. The Menstrual Disorder Of Teenagers (MDOT) Study: determining typical menstrual patterns and menstrual disturbance in a large population-based study of Australian teenagers. BJOG. 2010; 117(2): 185–92. doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.2009.02407.x.

- Delgado D. Validation of digital visual analog scale pain scoring with a traditional paper-based visual analog scale in adults. Journal AAOS. 2018;2(3):e088.

- Lamvu G, Carrillo J, Ouyang C, Rapkin A. Chronic pelvic pain in women: a review. JAMA. 2021;325(23):2381–91. doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.2631.

- Taboo, Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taboo.

- Perović M, Jacobson D, Glazer E, et al. Are you in pain if you say you are not? Accounts of pain in Somali–Canadian women with female genital cutting. Pain. 2021;162(4):1144–52. doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000002121.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (3rd ed., Revised (DSM-III-R)). Washington DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1987.

- Melzack R. The McGill Pain Questionnaire: major properties and scoring methods. Pain. 1975;1:277–99.

- Chung MK, Chung RR, Gordon D, Jennings C. The evil twins of Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome: endometriosis and interstitial cystitis. JSLS: Journal of the Society of Laparoendoscopic Surgeons. 2002;6(4):311–14.

Leave a Reply