Are you a visual learner? Or do you learn best by doing, or by reading a textbook? Does a podcast or audiobook work best for you?

The concept of learning styles states that people can be classified according to a content delivery method, or style, that differs between individuals: we learn best when our suited learning style is used.

Many models of learning styles have been described, but by far the most common is New Zealander Neil Flaming’s VARK model.1

In the VARK model, there are four sensory modalities:

- Visual learners: pictures or demonstrations

- Auditory learners: listening to an explanation

- Reading/writing learners: text

- Kinaesthetic learners: physically interacting with the world (doing)

Development of the VARK model was based on the observation that some excellent teachers did not reach all students effectively, while some bad teachers manage to teach a subset of students well.

This led to the idea that if learners could be classified by their innate learning style, then they could be taught more effectively using their individually suited modality.

In practice, a VARK questionnaire can be used to divide a class of students into visual, auditory, reading/writing, and kinaesthetic learners. The same curriculum can then be delivered in these different formats. According to the learning styles hypothesis, these students will learn better, and therefore have higher performance in an assessment, than if they were all taught together with the same method.

This is just common sense though right? As someone who has spent their entire life learning, you probably have a preferred learning style, or at least a style you dislike. Perhaps you would prefer to do all of your learning through a book, or via a podcast as you commute to work.

Learning styles are a myth

Sorry to bury the lead, but in fact, disability aside, that we each have individual learning styles is a myth. We may have a preference of how we like to learn, but there is a large body of evidence refuting that we learn better by using a preferred learning style.

This may at first be hard to accept. Afterall, belief in the utility of learning styles is more common than not, even amongst educators and scientists.2 On a more personal level, the corollary that we all learn in the same way conflicts with our desire to be unique, as well as our past experiences.

You might consider yourself a visual learner, and recall diagrams from medical school or a textbook that you can still picture today. But what about the auditory learning experience of being grilled by your consultant that you’ll never forget? Or the kinaesthetic sensation of a Veress needle traversing the layers of the abdominal wall. Would you have learned these better with a diagram?

You may also be, or know, a musician who can hear and understand pitches and tones more effectively than others. But although that person is better suited to learning music, a map will still be best for learning geography.

Evidence

There are two facts at the core of the myth:

- Many people have a preference for how they receive information.

- Evidence suggests that teachers achieve the best educational outcomes when they present information in multiple sensory modes.3

A landmark article evaluating learning style literature published in an Association for Psychological Science journal in 2009 found a lack of evidence to support the use of learning styles.4 It concluded that, at present, there is no adequate evidence base to justify incorporating learning style assessments into educational practice.

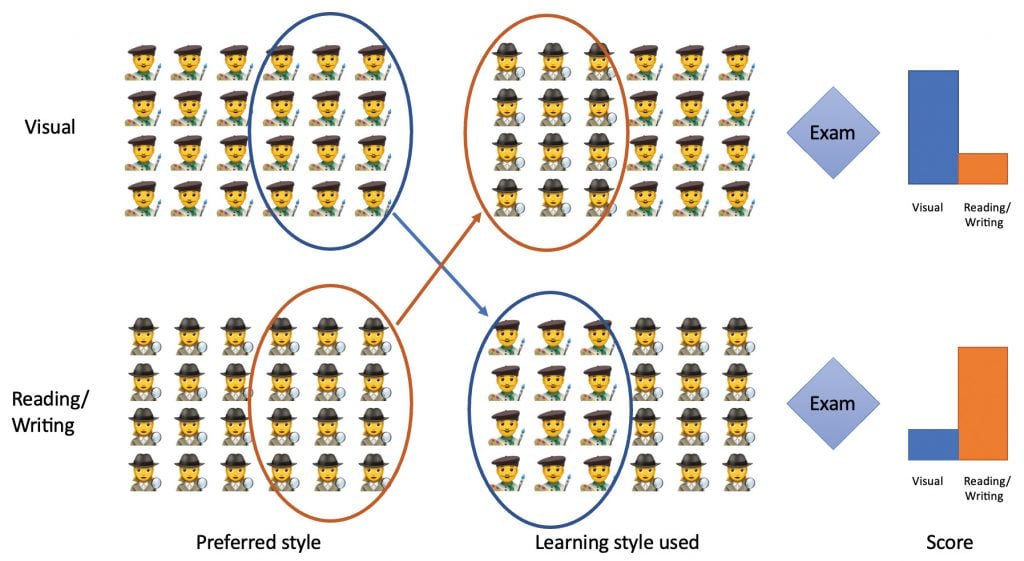

Evidence to support use of learning styles should come from randomised controlled trials (Figure 1). A group of students complete a questionnaire to determine their preferred format; for example, visual learners and reading/writing learners. They are then randomised to use either their preference, or the alternative. Only if those using their preferred learning style outperform the others, in both groups, do the results support the hypothesis.

Figure 1. Randomised controlled trial design with visual and reading/writing learning style arms. Exam scores shown would support the effectiveness of using a preferred learning style, but this is not observed in trials.

These trials have been conducted, and a follow-up review in 2015, incorporating these high-quality studies and concluded that the evidence for learning styles was virtually non-existent, while evidence contradicting it was both more prevalent and used more sound methodology.5

Regarding subject-specific matter, a 2018 study of 426 university anatomy students surveyed their learning styles using an online VARK questionnaire at the beginning of the semester.6 At the end of the semester, students reported poor correlation between their utilised study method and their preferred learning style. Those that did employ their preferred learning style performed no better than their peers. Similar studies have reported similar conclusions.7

Delivery of a curriculum using learning styles is resource intensive. It requires determination of each student’s learning style and preparation of educational material in multiple formats. Furthermore, certain styles may be less engaging, or time inefficient, reducing their uptake by learners.

Limitations

Evidence aside, it must be stated that utilising a preferred learning style is not without merit. The studies that make up the evidence base have focused on examination performance as the primary outcome. It is not known if this translates to long-term retention of information, nor enjoyment, engagement, or satisfaction with education.

Radiology podcasts, which seem to be an oxymoron, are popular, enjoyable, and a safe way to learn radiology while driving. Learning a visual specialty through audio alone is probably suboptimal (though evidence is lacking), but is certainly competitive with a textbook or computer screen while on the motorway.

Better ways to learn

The way that we teach and learn can always be improved. There is evidence to support multimodal teaching, which can simply be thought of as combining learning styles, such as the use of words with pictures rather than a picture alone. More complex examples include cognitive training combined with non-invasive brain stimulation and physical exercise training, or active control training in adaptive visual search and change detection tasks. Multimodal methods have been shown to significantly enhance learning and promote skill learning across multiple cognitive domains.3

Microlearning refers to short learning activities with microcontent.8 This is facilitated through small learning units and short-term educational activities. The most obvious examples of microlearning are abundant on TikTok, YouTube, and Instagram, but can also be found on posters and screensavers in hospitals, or delivered in the form of quick learning points at the beginning of handover. Macrolearning focuses on education at a larger scale, at the level of institutions and schools. A curriculum is delivered over a longer period of time and may incorporate a spiral or progressive approach. Macro/micro learning is a new research paradigm, and while not as well studied or described as learning styles, shows obvious promise in terms of engagement and accessibility.9

Inference

There are still good and bad ways to learn. They are just not dependent on the individual learner. Accept the evidence and acknowledge that bias perpetuates the myth that we each have a unique learning style. Employ the teaching modality best suited to the subject matter, and consider optimising content delivery through multimodal and macro/micro education.

If you remain unconvinced, try another learning style:

- Veritasium. The Biggest Myth in Education (YouTube)10

- Skeptoid Podcast: Learning Styles, Re-examined11

References

- Fleming ND. Teaching and learning styles: VARK strategies. 2001. Christchurch, New Zealand.

- Pashler H, McDaniel M, Rohrer D, et al. Learning styles: Concepts and evidence. Psychol Sci Public Interest. 2009;9(3):105-19.

- Ward N, Paul E, Watson P, et al. Enhanced learning through multimodal training: evidence from a comprehensive cognitive, physical fitness, and neuroscience intervention. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):1-8.

- Pashler H, McDaniel M, Rohrer D, et al. Learning styles: Concepts and evidence. Psychol Sci Public Interest. 2009;9(3):105-19.

- Cuevas J. Is learning styles-based instruction effective? A comprehensive analysis of recent research on learning styles. Theory Res Educ. 2015;13(3):308-33.

- Husmann PR, O’Loughlin VD. Another nail in the coffin for learning styles? Disparities among undergraduate anatomy students’ study strategies, class performance, and reported VARK learning styles. Anat Sci Educ. 2019;12(1):6-19.

- Cuevas J. Is learning styles-based instruction effective? A comprehensive analysis of recent research on learning styles. Theory Res Educ. 2015;13(3):308-33.

- Lindner M. Use these tools, your mind will follow. Learning in immersive micromedia and microknowledge environments. The Next Generation: Research proceedings of the 13th ALT-C conference. 2006:p.41-9).

- Aldosemani TI. Microlearning for Macro-outcomes: Students’ Perceptions of Telegram as a Microlearning Tool. InDigital Turn in Schools—Research, Policy, Practice. 2019:p.189-201. Springer, Singapore.

- Veritasium. The Biggest Myth in Education. YouTube. 2021. Available from: youtu.be/rhgwIhB58PA

- Dunning B. Learning Styles, Re-examined. Skeptoid Podcast. 2021. Available from: skeptoid.com/episodes/4764

Leave a Reply