Cancer management has changed. In the last 20 years, despite an increase in cancer incidence in Australia, mortality rates have decreased while disease-free survival rates remain high.1 Reproductive potential is a major determinant of quality of life in cancer survivors, and providers need to have an understanding of fertility preservation options with a pragmatic approach for accessing these services around the country.2 As such, current clinical practice guidelines recommend that all reproductive-age patients with a cancer diagnosis be offered, and have documented, a fertility preservation discussion to allow autonomous decision making in a timely fashion to prevent any regret, remorse or medico-legal implications.3 4

Within the confines of the patient’s reproductive potential, governed principally by their gender and age, chemo and radiotoxicity are determined by the choice of agent, the duration and intensity of the protocol. The Clinical Oncology Society of Australia outlines the impact of various protocols and provides clinical practice guidelines.5 At the most fundamental level, discussions with cancer patients need to include options for fertility preservation such as oocyte cryopreservation, ovarian tissue preservation, semen freezing, testicular tissue cryopreservation, medical and surgical options to minimise damage during cancer treatment as well as third-party reproductive options such as gamete donation and surrogacy.

Patients and their families need to be made aware that there is no evidence that fertility treatment could diminish their chance of successful cancer treatment, nor increase recurrence, even in hormone-sensitive cancers. Conversely, fertility preservation will not guarantee reproductive success in the future.

Chemotherapy

In the female, chemotherapy exerts immediate effects through damage to the growing follicular pool. This effect may be temporary or more permanent depending on the resting ovarian cohort of primordial follicles. Ovarian function may recover subsequently, usually over six months, although there may be long-term effects on quality as well as the risk of premature ovarian insufficiency. The overall impact of chemotherapy on an individual’s ovarian function will depend on their baseline ovarian reserve and age, the type of agents used (alkylating agents being more gonadotoxic), dose, duration, and frequency of administration.6

Radiation therapy

Radiotherapy, whether targeted abdominopelvic radiotherapy or total body irradiation may affect fertility by radiation-induced damage to the target organ, such as myometrial fibrosis, loss of elasticity, vascular damage and subsequent secondary hypoestrogenic effect. These changes may impact implantation, placentation and effect ongoing pregnancy, resulting in a higher risk of preterm birth, lower birthweight, uterine rupture, pre-eclampsia and stillbirth. Unfortunately, total treatment doses alone cannot accurately predict uterine damage or subsequent risk of complications and should be assessed prior to reproduction and childbearing.7 Suitability for pregnancy should involve liaison with radiation oncologists, obstetric physicians and a high-risk pregnancy clinic. Assessment of uterine functionality may be performed with ultrasound and/or MRI to assess uterine volume, doppler and endometrial thickness, and consideration given to an endometrial biopsy prior to an embryo transfer.8

Similarly, radiation and chemotherapy have an immediate and direct effect on sperm function but may also damage germinal epithelium and spermatogonia. This translates into altered sperm production, sperm DNA damage, and, more rarely, altered endocrine function. While these damaged sperm will in time be ejaculated or undergo apoptosis, semen parameters themselves may take years to recover.9

Patient communication

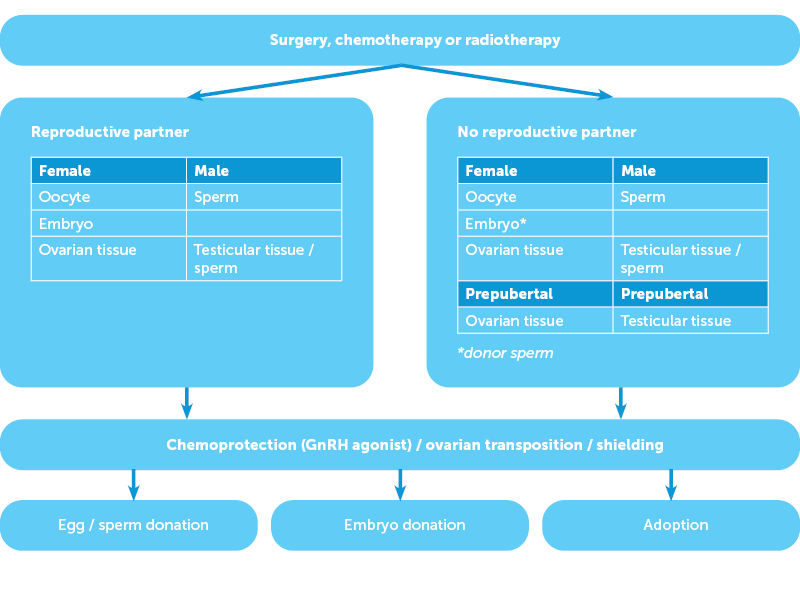

Fertility preservation often occurs in an emergent setting in coordination with the patient, their partner, family and often a surgical and oncological team. The discussion of reproductive options in a person-centred setting must consider the patient, his or her reproductive intent and that of any given partner, the type of cancer and the planned intervention. Simple decision matrices may be used to facilitate this communication (Figure 1) at a time when patients can feel overwhelmed with the volume and complexity of information presented. Fertility preservation counselling should only be performed by specialists with experience or appropriate training in this field and patients should have clear answers to the important decision points (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Patient communication aid

- Will the fertility treatment delay my chemotherapy / radiotherapy / surgery?

- Will the fertility treatment affect the success of my chemotherapy / radiotherapy / surgery?

- What is the chance of loss of fertility with my chemotherapy / radiotherapy / surgery?

- What is the chance of loss of ovarian function with my chemotherapy / radiotherapy / surgery?

- What is the chance of success of the fertility therapy?

- Will my chemotherapy / radiotherapy / surgery affect my ability to carry a pregnancy / give birth / breastfeed / care for a child?

Female fertility preservation options

In post-pubertal females, embryo or oocyte cryopreservation is an established practice. Recent evidence has confirmed the efficacy of the random start protocol, so that stimulation may commence at any time in the ovulatory cycle.10 Medications such as letrozole can be added to the usual gonadotropin stimulation to reduce oestrogen levels in hormone-sensitive cancers, while GnRH triggers are utilised to reduce the risk of complications such as ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. Oocyte cryopreservation has excellent survival rates, and although lower than non-cancer patients, comparable implantation and clinical pregnancy rates.11

In the pre-pubertal female, where oocyte or embryo cryopreservation is not possible, ovarian tissue cryopreservation has now transitioned from ‘experimental’ to a practice endorsed by the American Society of Reproductive Medicine and European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology. This technique also offers an immediate fertility preservation option for post-pubertal females when cancer treatment is imminent. Once ovarian tissue has been removed, the cortex is prepared and then cryopreserved. When fertility is desired, this tissue is thawed and auto-transplanted into the pelvis or into other areas of the body, after the tissue has been tested for the residual tumour or other biomarkers.12 13 Re-introduction of malignant cells has not been reported in humans to date. Following transplantation, conception may occur unassisted or by IVF, with research into novel treatments continuing.

Ovarian transposition out of the radiation field and shielding can also reduce potential ovarian damage. In the post-pubertal female, GnRH analogs may have a role in chemoprophylaxis in certain cancers, such as the breast.14 Proposed mechanisms for GnRH analogues in reducing the risk of damage to the ovary include simulation of the prepubertal hypogonadotrophic milieu, reduced ovarian perfusion and up-regulation of ‘ovarian protecting’ molecules.

Table 1. Options for female patients (adapted from COSA5)

| Egg freezing | Embryo freezing | Ovarian tissue freezing | |

| Partner or donor required | No | Yes | No |

| Time required | 2 weeks | 2 weeks | 1 day |

| Pubertal status | Post-pubertal | Post-pubertal | Pre- or post-pubertal |

| Survival rates of tissue | 60% | 95% | Reasonable |

| Expectation of success | Good if enough eggs collected | Excellent if enough embryos | Low currently |

| Chemotherapy | GnRH agonists during chemotherapy | ||

| Radiation | Ovarian transposition out of radiation field | ||

| Third-party parenting options | Egg donation, embryo donation, surrogacy, adoption | ||

Male fertility preservation options

Sperm cryopreservation is well-established in post-pubertal males (see Table 2). Depending on the sperm concentration, the ejaculate may be distilled into multiple vials, each allowing one attempt at natural conception (intrauterine insemination) or one cycle of IVF. For men unable to produce a semen sample, surgical sperm retrieval or, rarely, vibro-stimulation, provide established alternatives. In the absence of mature sperm production, pre-pubertal males present a challenge as the isolation of spermatogonial stem cells from testicular tissue is challenging. Currently, testicular tissue cryopreservation is considered experimental, and offered by limited units in Australia in the context of ethically approved research.15

Table 2. Options for male patients

| Sperm cryopreservation | Testicular tissue cryopreservation | |

| Pre- or post-pubertal | Post-pubertal | Pre-pubertal |

| Experimental | No | Yes |

| Survival rates of tissue | Good | Unsure |

| Partner required | No | No |

| Time frame | Immediate | 1–2 days |

| Invasiveness | Nil | Minimal–moderate |

| Surgical shielding of testes | ||

| Third-party parenting options | Sperm donation, surrogacy, adoption | |

Access

Access to oncofertility services varies significantly across Australia and New Zealand. The nature of cryopreservation services has laid the onus onto the assisted reproductive technology (ART) sector, although specialised public hospital clinical departments that focus on oncofertility services have arisen more recently. A number of studies have shown that barriers to care include lack of insurance, financial burden, difficulties with referrals, lack of funding for research and lack of donated tissues.16 17 Affordable access to fertility services thus remains location dependent, with limited public tertiary hospital fertility preservation services, despite referral pathways for patients in remote and rural areas. Many private fertility units provide oncofertility services with Medicare rebate with no, or minimal, cost to the patient. Sparce and geographically challenging service provisions can make integration of fertility and oncology services challenging. The establishment of dedicated, accessible oncofertility support and research services is invaluable for both clinical research and comprehensive fertility preservation and psychosocial support.18

Conclusion

Oncofertility has established itself as a significant discipline within our field, with emerging dedicated services in both the public and private sectors. With increasing rates of cancer diagnosis, improved treatment and cancer-free survival, it is imperative that we continue to strive towards efficient, accessible multidisciplinary services, irrespective of location or geographical challenges, that can be accessed by all.

Our feature articles represent the views of our authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RANZCOG), who publish O&G Magazine. While we make every effort to ensure that the information we share is accurate, we welcome any comments, suggestions or correction of errors in our comments section below, or by emailing the editor at [email protected].

References

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Canberra ACT: Cancer in Australia; 2021. Available from: www.aihw.gov.au/reports/cancer/cancer-in-australia-2021/summary

- Howard-Anderson J, Ganz PA, Bower JE, Stanton AL. Quality of life, fertility concerns, and behavioral health outcomes in younger breast cancer survivors: a systematic review. J of Nat Ca Inst. 2012;104(5): 386-405.

- Oktay K, Harvey BE, Loren AW. Fertility preservation in patients with cancer: ASCO clinical practice guideline update summary. J of Onc Practice. 2018;14(6): 381-5.

- Hohmann C, Borgmann-Staudt A, Rendtorff R, et al. Patient counselling on the risk of infertility and its impact on childhood cancer survivors: results from a national survey. J of Psychosoc Oncol. 2011;29(3): 274-85.

- Clinical Oncology Society of Australia. Sydney NSW: AYA cancer fertility preservation guidance working group. Fertility preservation for AYAs diagnosed with cancer: Guidance for health professionals. Available from: cancer.org.au/clinical-guidelines/cancer-fertility-preservation/?title=COSA:AYA_cancer_fertility_preservation

- Cobo A, Garcia-Velasco JA, Remohi J, Pellicer A. Oocyte vitrification for fertility preservation for both medical and nonmedical reasons. Fertil Steril. 2021;115(5):1091-101.

- Rosen G, Rogers P, Chander S, et al. Clinical summary guide: reproduction in women with previous abdominopelvic radiotherapy or total body irradiation. Hum Repro Open. 2020. doi.org/10.1093/hropen/hoaa045

- Rosen G, Rogers P, Chander S, et al. Clinical summary guide: reproduction in women with previous abdominopelvic radiotherapy or total body irradiation. Hum Repro Open. 2020. doi.org/10.1093/hropen/hoaa045

- Mulder RL, Font-Gonzalez A, Green DM, et al. Fertility Preservation in Childhood, Adolescent, and Young Adult Cancer 2 Fertility preservation for male patients with childhood, adolescent, and young adult cancer: recommendations from the PanCareLIFE Consortium and the International Late Effects of Childhood Cancer Guideline Harmonization Group. Lancet Oncology. 2021;22(2):E57-67.

- Boots CE, Meister M, Cooper AR, et al. Ovarian stimulation in the luteal phase: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2016;33:971–80.

- Cobo A, Garcia-Velasco JA, Remohi J, Pellicer A. Oocyte vitrification for fertility preservation for both medical and nonmedical reasons. Fertil Steril. 2021;115(5):1091-101.

- Gook D, Hale L, Polyakov A, et al. Experience with transplantation of human cryopreserved ovarian tissue to a sub-peritoneal abdominal site. Hum Reprod. 2021;36(9):2473-83.

- Stern CJ, Gook D, Hale LG, et al. First reported clinical pregnancy following heterotopic grafting of cryopreserved ovarian tissue in a woman after a bilateral oophorectomy. Hum Reprod. 2013;28(11):2996-9.

- Senra JC, Roques M, Talim MC, et al. Gonadotropin‐releasing hormone agonists for ovarian protection during cancer chemotherapy: systematic review and meta‐analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2018;51(1):77-86.

- Coccia PF, Pappo AS, Beaupin L, et al. Adolescent and young adult oncology, version 2.2018, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2018;16(1):66-97.

- Rashedi AS, de Roo SF, Ataman LM, et al. Survey of fertility preservation options available to patients with cancer around the globe. J Glob Oncol. 2018;4:1–16.

- Australian Government. Canberra ACT: Cancer Australia; National Service Delivery Framework for Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer. 2008. Available from: https://www.canceraustralia.gov.au/sites/default/files/migrated-files/publications/national_service_delivery_framework_for_adolescents_and_young_adults_with_cancer_teen_52f301c25de9b.pdf

- Future Fertility. Sydney NSW: Future Fertility. 2018. Available from: www.futurefertility.com.au

Leave a Reply